Daikin claimed PFOA emission levels are confidential, Osaka Prefecture dropped issue(10)

2022.02.10 17:06 Nanami Nakagawa

Signboard for the Aigawa River near Daikin Industries' Yodogawa Plant

From 2006 to 2008, Daikin Industries Chairman Noriyuki Inoue served as head of a supporters’ group for then Osaka Governor Fusae Ota. Daikin itself contributed to the supporters’ group by buying tickets for political fundraising parties. During this period, the Osaka prefectural government already knew the world’s highest recorded level of toxic chemical PFOA had been detected in one of the city’s rivers — and that the pollution had been caused by Daikin.

Given the ties between the governor and Daikin’s chairman, had the prefectural government adequately urged the company to take PFOA pollution countermeasures? At both a prefectural assembly session at the time and, more recently, in response to questions from Tansa, Ota was confident the issue had been addressed.

However, Tansa obtained evidence through a freedom of information request that undercut the former governor’s assurances: records of the prefecture’s hearings with Daikin. In them, the prefecture is hesitant to confront the polluter.

Daikin: “No basis for EPA standard”

The first hearing with Daikin, attended by four officials from Osaka Prefecture’s business guidance section and environmental protection section, began at 10 a.m. on June 22, 2007. The company had brought six employees, including a full-time director from the head office, a chemical division section head, and a division manager from the Yodogawa Plant.

There were both domestic and international reasons why the prefecture had to confront Daikin.

First, domestic: In 2004, following a survey of rivers across Japan, a research team led by Kyoto University Professor Akio Koizumi had found that the Aigawa River, a tributary of the Yodogawa River near Daikin’s Yodogawa Plant, contained the world’s highest recorded concentration of PFOA. The team had also measured PFOA levels in the blood of residents in 10 locations across the country, finding the highest levels in residents of Osaka City. The concentration of PFOA in the city’s tap water was 300 times higher than in Sendai City; since Osaka City’s tap water is mainly collected from the Yodogawa River, the team hypothesized tap water was causing residents’ high PFOA levels.

As for the international reasons, in January 2006 the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) had proposed that eight of the world’s largest PFOA manufacturers, including Daikin, should end PFOA production by 2015. By March of the same year, all eight companies had agreed to the EPA’s plan. By that time, PFOA manufacturers in the U.S. had already begun feeling the pressure. For example, following a lawsuit, in 2004 DuPont agreed to a $70 million settlement for residents impacted by PFOA pollution and $10 million for water purification measures.

In its hearing with the Osaka prefectural government, Daikin explained the EPA’s PFOA reduction program and wastewater treatment for manufacturing processes that use significant amounts of the chemical.

Many of the prefecture’s questions were relatively elementary, such as “What companies produce fluoropolymers in Japan?” They seemed unprepared to conduct the hearing.

The prefecture also asked about the EPA’s safety standard for PFOA in drinking water. According to findings by Koizumi’s research team, tap water in Osaka City was nearing the EPA’s standard, and the prefectural government knew it.

“Is the EPA’s standard based on some sort of risk assessment?” the prefecture asked.

“There is no basis as such,” Daikin replied. “It’s probably because the previous standards were too loose.”

Although Daikin had agreed to the EPA’s plan to end its PFOA production, in its conversation with the prefecture, the company seemed not to take the EPA’s drinking water safety standard seriously. The prefecture didn’t comment on Daikin’s stance nor ask any follow-up questions.

The hearing ended after two hours.

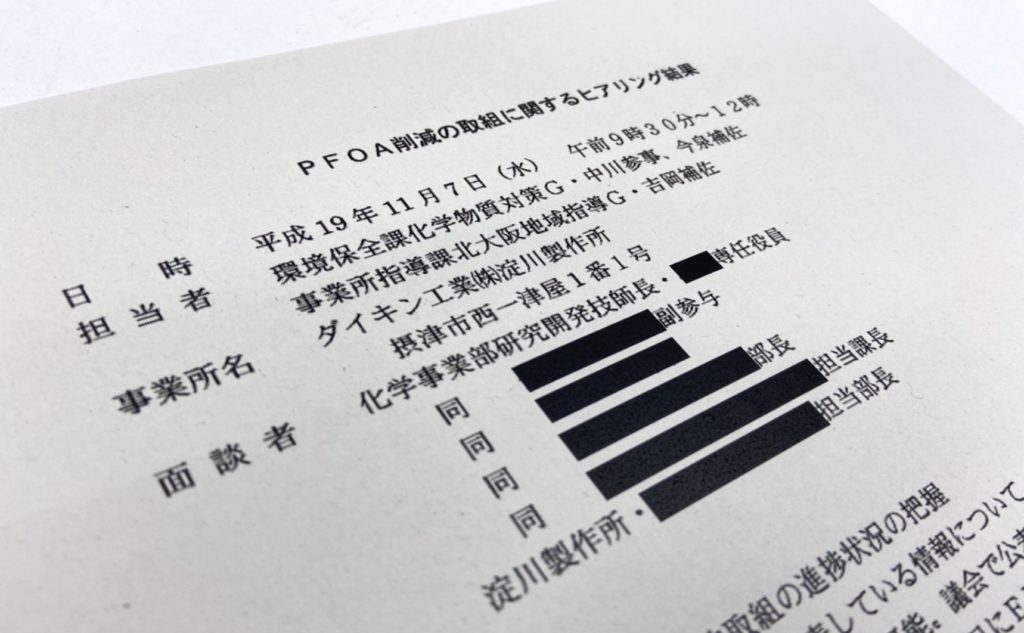

Record of a hearing with Daikin kept by the Osaka prefectural government

Osaka prefecture: “Japan doesn’t have an agreed upon PFOA toxicity standard, so…”

The two parties met for another hearing five months after the first, on Nov. 7, 2007. Once again, Daikin executives and others were there to represent the company.

One of the hearing’s key issues was progress on the EPA’s program to end PFOA production by 2015.

The plan first aimed for each of the eight companies to achieve a 95% reduction from 2000 emissions levels by 2010. Osaka prefecture asked what Daikin’s PFOA emissions had been in 2000.

“We do not disclose our emissions because they are CBI (confidential business information),” the company responded. “If we did, our production volume would be revealed.”

Daikin had refused to answer the prefecture’s question.

Without knowing the volume of PFOA emissions, it would be difficult for the prefecture to assess the extent of the pollution. But, at the hearing, the prefecture didn’t press the issue.

High levels of PFOA had been detected in the blood of prefectural residents — were the public servants really doing their duty? Had Daikin ever disclosed its PFOA emissions to the prefecture after the Nov. 7, 2007 hearing?

To find out, Tansa interviewed by phone Tsuyoshi Kubota, current chief inspector in the Osaka prefectural government’s chemical substance countermeasures group, business guidance section, environmental management office. His section had been one of the ones conducting the Daikin hearings.

Has the prefecture received reports from Daikin on its PFOA emissions?

“I can’t answer that because it’s confidential corporate information.”

We’re not asking you to tell us the exact level of emissions, just whether the prefecture knows what they are.

“I can’t answer that either.”

This concerns the health of prefectural residents. The Freedom of Information Act requires information related to human life and health be made public, even if it risks damaging corporate profits. Why can’t you give an answer?

“Contaminated water isn’t being consumed, and Japan doesn’t have an agreed upon PFOA toxicity standard, so…”

Daikin’s response to PFOA pollution had been called too slow at an Osaka prefectural assembly session in September 2007. In response, then Governor Ota had responded, “We are taking a leading role in the PFOA issue, not lagging behind.”

But at the hearing — conducted two months after Ota’s comments in the prefectural assembly — Daikin had not even informed the prefecture of its PFOA emission levels.

Daikin rejected suggestion to explain PFOA situation to locals

In 2007, Ota was being lambasted by the media and opposition party members for mixing politics and money. She decided not to run for a third term and, in 2008, was succeeded as governor by Toru Hashimoto.

However, the prefecture still had difficulty dealing with Daikin.

On Aug. 27, 2009, during a meeting between the prefecture and Daikin, the prefecture made the following proposal as they discussed PFOA countermeasures.

“Why don’t we use opportunities such as the Bon Dance Festival at the Yodogawa Plant to inform people of our initiatives to protect the local environment?”

“We already do this during plant tours and other events,” Daikin responded. “The Bon Dance Festival has a different purpose, so it’s difficult to talk about environmental countermeasures there.”

The prefecture made a counter-proposal.

“Then how about the prefecture, Settsu City, and Daikin jointly discuss our PFOA-related initiatives at events or opportunities where it is appropriate?”

But Daikin refused: “At the moment, there have been no inquiries from the local community about PFOA. If it’s going to stir up anxiety, and since we’ll soon be stopping PFOA production, we’d like to avoid mentioning it as much as possible.”

To be continued.

(Originally published in Japanese on Feb. 4, 2022. Translation by Annelise Giseburt.)

Polluted with PFOA: All articles

Newsletter signup

Newsletter signup