How Settsu City, at Daikin’s request, kept PFOA pollution secret from citizens (6)

2022.01.27 17:45 Nanami Nakagawa

Settsu Mayor Kazumasa Moriyama at Settsu City Hall on Dec. 10, 2021.

In fall 2021, students from Ajifu Elementary School in Settsu City, Osaka Prefecture, harvested rice from a field near Daikin Industries’ Yodogawa Plant. High levels of toxic chemical PFOA have been detected in the blood of residents who ate vegetables from the adjacent field. The children too risk ingesting PFOA by eating the harvested rice.

In an interview with Tansa, Settsu City Mayor Kazumasa Moriyama (78) admitted his personal opinion that students should not take home the rice they harvested, but he left the final decision to the board of education. As of this writing, discussion is still ongoing.

One clue as to why the Settsu officials, even the mayor, are avoiding a decision can be found in the tripartite meetings held by Daikin, Settsu City, and Osaka Prefecture, the content of which has been kept from the public.

Tansa obtained meeting minutes through a freedom of information request and other reporting. The minutes reveal that officials from Settsu City, whose public finances and employment have been buyoned by Daikin, have been following Daikin’s request for secrecy — despite potential harm to citizens.

Daikin told resident it’s fine to use groundwater for fields

When members of the Settsu City environmental policy division arrived for a meeting at the Daikin Yodogawa Plant on Dec. 25, 2019, they were ushered into a reception room in the plant’s Technology Innovation Center (TIC), which had been built four years earlier.

Also present were five Daikin employees, including the heads of the chemical divisions from both company headquarters and the Yodogawa Plant, as well as two members of the project guidance group from the Osaka prefectural government’s environmental management office.

It was a meeting about PFOA.

In May 2019, PFOA had been added to the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants as a highly dangerous chemical — and one that must be eliminated. Chemicals included in the convention are highly toxic and harmful to the human body. In Japan, a party to the convention, it was clear that domestic regulations regarding PFOA would be strengthened.

At the meeting, which began at 10 a.m., Daikin employees reported the results of a water quality survey the company was conducting.

An employee began by explaining the PFOA concentration in well water on the Yodogawa Plant grounds. One of the observation wells, which had previously been on a downward trend, was now showing an increase. The employee attributed it to the fact that a pumping treatment to reduce the PFOA concentration had stopped during the construction of the TIC building.

The PFOA concentration in water discharged into the sewage system had not decreased either, and a prefectural government representative asked why.

“Sometimes it remains in the equipment, or sometimes the equipment is removed but the surrounding flooring and gutters are not replaced,” a Daikin employee responded. “We believe it is from process wastewater, including rainwater flowing from the plant.”

During the meeting, Daikin also reported on inquiries from nearby residents.

“We received one inquiry asking whether there was any problem in using groundwater to water fields. We said there wasn’t.”

The meeting ended in an hour.

The Technology Innovation Center at Daikin Industries’ Yodogawa Plant, where the tripartite meetings were held. From Daikin Industries’ YouTube channel.

City told residents it doesn’t know pollution source

The next tripartite meeting was held six months later, on June 30, 2020. A few weeks earlier, on June 11, the Ministry of the Environment had released the results of a nationwide PFOA survey, which found groundwater in Settsu City to have the highest concentration of the chemical in Japan.

The group convened at 1 p.m. in the same location, the Yodogawa Plant’s TIC building. The environment ministry’s survey results had been reported in the media, and the parties were updating each other on inquiries from residents.

“The city hasn’t told anyone about our tripartite meetings,” a Settsu City official then asked. “How much should we tell them?”

“We don’t want the PFOA concentration at the Yodogawa Plant site disclosed,” answered a Daikin representative.

“At the moment, when people ask where the pollution is coming from, we tell them we don’t know,” a city representative assured them.

They went on to explain the city’s policy on responding to inquiries from residents.

“We received an inquiry from a farmer who asked if it was safe to eat produce grown using well water. They were also concerned about PFOA in irrigation channels, so we plan to say there is no problem since Settsu City doesn’t use spring [well] water in our tap water.”

All members of the June 2020 tripartite meeting understood that Daikin was the source of the PFOA pollution. Daikin even explained why the concentration of PFOA in sewage water had not decreased.

And yet, city officials told none of this to citizens.

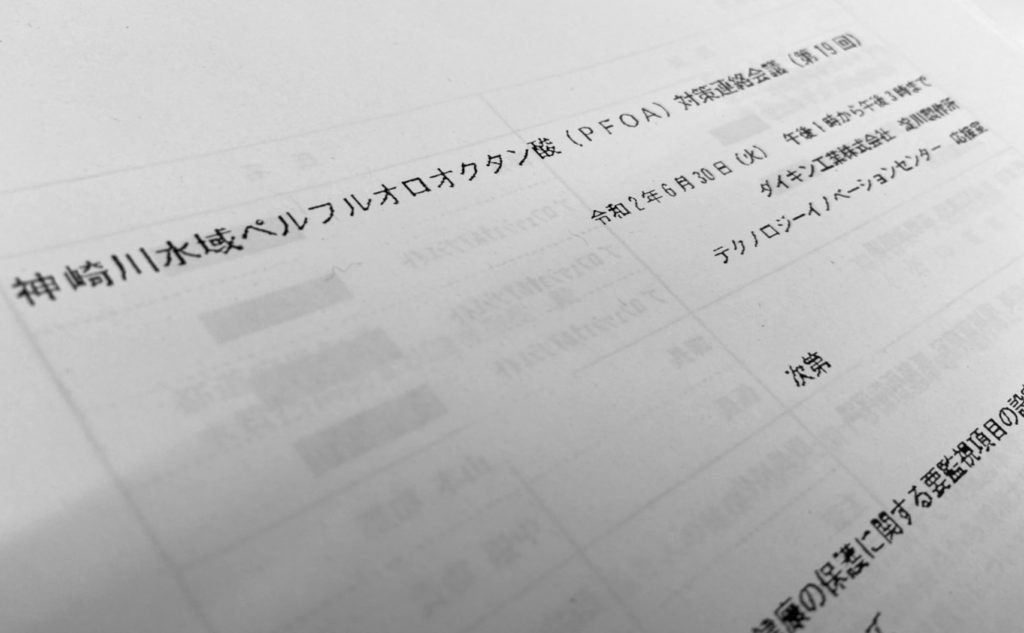

Minutes of the tripartite meeting kept by Osaka Prefecture.

Mayor: “We haven’t notified the public about the soil”

Following the environment ministry’s survey results, the situation in Settsu became even more serious when, in October 2021, the blood of nine residents near the Yodogawa Plant was found to have PFOA concentrations dozens of times higher than that of non-contaminated areas. All nine had eaten crops grown near the plant — despite city officials saying locally grown crops were safe to eat.

Expecting more forthcoming answers following this new development, Tansa interviewed Mayor Moriyama at Settsu City Hall on Dec. 10, 2021.

Settsu City officials told citizens they don’t know the cause of the pollution. Why?

“I don’t really know anything about that.”

The source of the pollution can only be Daikin, right?

“Settsu is an industrial city, so there may be other businesses, large or small, that use PFOA. But we know that Daikin used PFOA, so we’re holding the tripartite meetings to confirm whether Daikin is the cause.”

At a tripartite meeting in June 2020, the city said it would tell residents it’s “not a problem” to eat vegetables grown using groundwater. But residents eating said vegetables were found to have high levels of PFOA in their blood.

“I think what we meant when we said it’s ‘not a problem’ wasn’t that it’s ‘not a problem,’ but that there isn’t any clear benchmark value for when it becomes a problem.”

There’s a big difference between “not a problem” and “no one knows.”

“Hey, we’d love to know some sort of benchmark ourselves. But given that we don’t, there are things we can say and things we can’t.

“As for the soil, to be frank, we haven’t notified the public, since we haven’t got exact numbers yet. But I think we’re safe for now.”

To be continued.

(Originally published in Japanese on Jan. 7, 2022. Translation by Annelise Giseburt.)

Polluted with PFOA: All articles

Newsletter signup

Newsletter signup