The coal plant that “reduces” CO2 emissions from zero to 7.26 million tons

2021.09.09 15:01 Annelise Giseburt

JERA's coal-fired power plant under construction in Yokosuka, Kanagawa Prefecture. Photo taken on April 22, 2021.

A new coal-fired power plant is under construction in the city of Yokosuka, on the southwestern tip of Tokyo Bay.

Owned by JERA, a utility established in 2015 by Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) Fuel & Power and Chubu Electric Power Co., the coal plant will replace an old oil and gas plant operated by TEPCO since the 1960s.

Once both units come online in February 2024, the plant will emit 7.26 million tons of CO2 per year, four times the total emissions of Yokosuka city itself.

Yokosuka also happens to be home to Shinjiro Koizumi, Japan’s young minister of the environment. However, Koizumi has never spoken out against the coal plant currently under construction in his constituency.

In April 2021, the Japanese government announced that it was setting a new 2030 greenhouse gas emissions reduction target — 46% of 2013 levels, a significant leap from the previous target of 26%. The increase was intended to help bring Japan in line with the Paris Agreement’s goal of keeping global warming well below 2 degrees C and pursuing efforts to limit warming to 1.5 degrees C compared with pre-industrial levels.

According to a report by the nonprofit Kiko Network, CO2 emissions from coal-fired power plants account for about 20% of Japan’s total emissions. In energy generation alone, coal represents roughly 60% of emissions, according to government data. But despite the recent hike in emission reduction targets, Japan continues to build new coal-fired power plants.

In Yokosuka, locals have sued the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) in an attempt to halt the coal plant’s construction. Their suit targets the plant’s environmental impact assessment, which METI gave the final approval for.

In the impact assessment, JERA claims that the new coal plant will actually decrease emissions by replacing the old oil and gas plant.

But the old plant wasn’t even running.

Thermal and nuclear

The Yokosuka Thermal Power Station looks out onto Tokyo Bay from a roughly 800,000-square-meter plot in Yokosuka’s Kurihama neighborhood. Construction of the new coal units began in May 2019, and, at a glance, the project appears to be progressing quickly. Trucks continuously roll in and out through the main gate. Cranes and the looming shells of new facilities dominate the shoreline.

The oil and gas plant currently being replaced first came online in 1960, providing power to the Tokyo and Yokohama areas during Japan’s period of rapid economic growth.

Zoom out to see the Yokosuka power plant's location on the southwestern tip of Tokyo Bay.

But decreasing demand in a stalled economy, coupled with the plant’s aging facilities, eventually convinced then owner TEPCO to take the Yokosuka plant offline. In 2010, it entered a “long-term planned shutdown” and was manned only by a skeleton crew, in case it was needed in an emergency.

An emergency was right around the corner. Following the Fukushima nuclear disaster in March 2011, Japan took its entire nuclear fleet — which had provided 27% of the country’s power — offline. A few of the Yokosuka units in relatively good condition were brought back online to help make up for Japan’s energy shortage, but in April 2014 the plant once again entered long-term shutdown.

TEPCO announced its plan to replace the old Yokosuka plant with a new coal-fired one two years later, in April 2016 — the same month that Japan signed the Paris Agreement.

It may seem like ironic timing, but historically Japan’s approach to lowering emissions has been gradual reductions through improving its thermal power generation technologies, rather than switching out thermal for renewables.

“Japan’s major utilities haven’t aggressively invested in renewables and have lacked experience, until recently,” explains Gregory Trencher, an associate professor at the Kyoto University Graduate School of Global Environmental Studies.

“Instead, the utilities’ strength is in thermal and nuclear power. And since they monopolize the regional grids, they sometimes make it difficult for companies doing renewables to gain access.”

When TEPCO announced its plans for the Yokosuka plant in 2016, the energy mix from its existing power plants was as follows.

・Light natural gas (LNG): 65%

・Coal: 20%

・Oil: 4%

・Renewable energy purchased from other sources: 4%

・Hydro: 3%

・Solar, wind, small-scale hydro, biomass, geothermal: 3%

・Other: 1%

Even including hydropower, renewable energy generated by TEPCO itself only made up 6% of its total.

Still, the global push for decarbonization continues to gain strength, even in Japan. Coal in particular is increasingly vilified. But TEPCO, succeeded by JERA in the management of the Yokosuka plant from September 2016, found a way to put a positive spin on 7.26 million tons of CO2.

Yokosuka coal-fired power plant under construction. Photo taken on April 22, 2021.

Greenwashed with emission data from early 1970s

Before a new power plant is built, the owner needs to conduct an environmental impact assessment (EIA), which includes evaluating the impact of pollution and noise on the surrounding area, as well as receiving statements of opinion from heads of local government. Large-scale plants like Yokosuka also require a statement of opinion from the environment minister and final approval from METI.

However, in 2012 the Japanese government introduced an “easy mode” for thermal power plant EIA. If a new plant replaces an older, less efficient one and thereby reduces CO2 and other types of emissions, it’s subject to a less vigorous assessment.

The stated objective of these new regulations, called “replacement guidelines,” was to help mitigate global warming. If an old, inefficient plant is emitting lots of CO2, the reasoning went, it makes sense to shorten the EIA and get a more efficient plant built quickly.

JERA’s Yokosuka coal plant is one such replacement project. In its EIA, the utility claimed that replacing the old oil and gas plant will reduce emissions.

This is a rather extreme misrepresentation of the facts.

The old Yokosuka plant had been inactive since 2014. It was emitting no CO2.

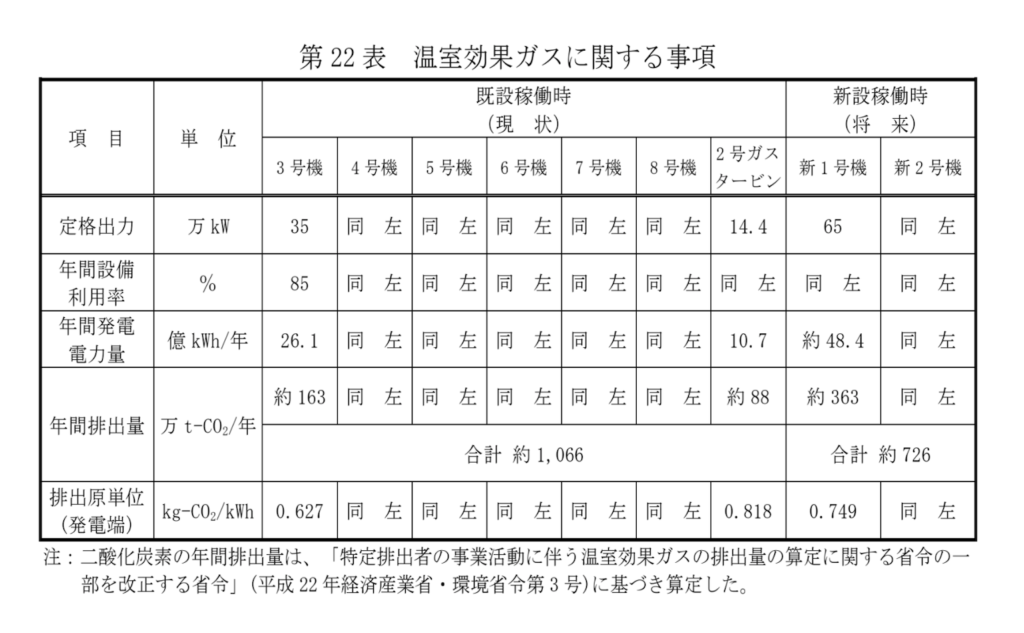

However, in the EIA, JERA compared the CO2 emissions of both the old and new plants at a utilization rate of 85% — 10.66 million tons to 7.26 million tons per year, respectively. The EIA did not state when the old plant had a utilization rate of 85%. It only included the notation “when running (present condition).”

Chart comparing the annual CO2 emissions of the Yokosuka power plant before and after its replacement. Taken from the new plant's environmental impact assessment.

This misrepresentation is a key element of the locals’ suit to stop the plant. Led by attorney Nobuo Kojima, the Yokosuka plaintiff group’s legal team investigated when exactly the old power plant had operated at 85% using data compiled by METI — the same ministry that had given final approval on the new plant’s EIA.

The legal team found that the old Yokosuka plant had most recently operated at 85% — releasing the EIA’s stated annual 10.66 million tons of CO2 — in the early 1970s.

METI approved the EIA anyway.

“They have the data — they know that the new plant does not actually reduce CO2 emissions,” Kojima says. “I never expected that TEPCO and METI would try to pull the wool over our eyes like this.”

In response to questions from Tansa, JERA’s public relations office gave the following explanation for conducting a simplified EIA under the government’s replacement guidelines.

“The guidelines were applied to this project for the following reasons, as well as the fact that when the EIA process began, the plant was in a long-term planned shutdown and could be restarted if necessary.

“Considering the life cycle of thermal power plants, it is inevitable that the utilization rate of plants with low thermal efficiency will decrease as they operate over a long period of time. The point of replacement is to upgrade them with plants with high thermal efficiency.

“The guidelines state that ‘Greenhouse gas emissions are to be calculated using the same utilization rate before and after replacement.’”

In JERA’s view, the old Yokosuka plant was a candidate for the replacement guidelines’ simplified EIA because, although it wasn’t running, it could resume operations if necessary. And the guidelines specified that greenhouse gas emissions needed to be calculated using the same utilization rate — if JERA planned to run the new plant at 85%, then they had to use that rate for the old one.

It appears it wasn’t necessary to mind the gap.

Environment minister not getting involved

One requirement for a large-scale power plant’s EIA is a statement of opinion from the minister of the environment. For the new Yokosuka plant, that opinion was given by the previous Environment Minister Yoshiaki Harada in August 2018. It was addressed to then Economy Minister Hiroshige Seko and contained the following.

“Japan ratified the Paris Agreement in 2016, and we need to work toward achieving its aims.

“The coal plant planned to be built in Yokosuka will add another 7.26 million tons per year to Japan’s CO2 emissions; this is an extremely high risk to the environment.”

In August 2019, toward the end of his term as environment minister, Harada summoned TEPCO President Tomoaki Kobayakawa to his office. In their meeting, Harada stressed the importance of curbing Japan’s coal power generation as much as possible and handed over a letter to the same effect.

Shinjiro Koizumi, the son of a former prime minister, took over as environment minister the next month. But he appeared to take a softer stance on coal than his predecessor.

Young protesters act out a scene in which Japan has declared that it will abandon coal by 2030; Biden-senpai notices and is pleased. From left to right, U.S. President Joe Biden, Japan Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga, Environment Minister Shinjiro Koizumi, Economy Minister Hiroshi Kajiyama. Photo taken in Yokosuka on April 22, 2021.

On Sept. 11, 2019, in his first press conference as environment minister, Koizumi had the following exchange with Jun Komine, a reporter from environmental paper Kankyo Shimbun.

“So, in your electoral district, the Yokosuka coal plant has finished its EIA, and four, five years down the line it will start pumping out CO2,” Komine began.

“Although you pay lip service to climate change, wouldn’t it be better to start by bringing in TEPCO President Kobayakawa and suggest putting a stop to the plant?”

Koizumi’s first words in response were “Yokosuka is a great place. Please come visit.”

He then continued, “We’re going to reduce coal power going forward. That’s the Japanese government’s policy, and I agree with it.

“I’m grateful to everyone in my electorate who voted me into office. But I believe it’s my job as a politician to consider what’s best for Japan overall, what’s best for Japan as part of the wider world. In particular, in my role as minister, I don’t think it’s right for me to take specific action just because I’m from Yokosuka.”

Does Koizumi still think the same way now, two years down the line? Tansa requested an interview with Koizumi through the environment ministry’s public relations office, but he turned us down, citing his busy schedule.

However, an individual familiar with Koizumi was more talkative. They speculated that the minister refuses to get involved with the Yokosuka coal plant for the following reasons.

・Koizumi believes that coal power is still a better option than bringing Japan’s nuclear fleet back online.

・METI, not the environment ministry, is in charge of approving new power plants. Koizumi is reluctant to pick a fight with METI, which has more power and influence than the environment ministry.

・Only a small number of people are actively opposing the Yokosuka plant. Members of opposition parties and citizens’ groups sometimes hold protests, but not too many.

Although Yokosuka may not be seeing a widespread anti-coal movement, the citizens opposing the plant know how to do a lot with a little: Their lawsuit against METI has the potential to stop the plant’s construction in its tracks.

Next time, we’ll take a closer look at what they are fighting for.

To be continued.

—————

This article is supported by the Judith Neilson Institute’s Asian Stories project, in collaboration with the Australian Financial Review, the Centre for Media and Development Initiatives Vietnam, the Korean Center for Investigative Journalism Newstapa, Malaysiakini, Tempo, and Tortoise Media.

Newsletter signup

Newsletter signup