The collapse of the offsite center (4)

2021.03.29 17:04 Nanami Nakagawa

Inside the offsite center, which was evacuated as the nuclear disaster progressed. Photo taken on June 20, 2014 by Shinshu Hida. (C) Shinshu Hida

At 11:20 a.m. on March 14, 2011, the commanding officer of a Self-Defense Forces unit tasked with rescuing patients left behind at Futaba Hospital and retirement home Deauville Futaba during the Fukushima nuclear disaster went to the nearby offsite center to use its phone to request backup.

Although his unit had managed to evacuate 132 patients that morning, there were still 92 left at the hospital, in addition to the bodies of three who had passed away. They needed help as soon as possible.

However, the commanding officer was refused entry. Following a second hydrogen explosion at Fukushima No. 1, the offsite center had sealed its doors and windows to protect those inside from radiation. Without access to a phone, the commanding officer was forced to drive 80 kilometers to the 12th brigade command center at Camp Koriyama.

However, Futaba Hospital Director Ichiro Suzuki didn’t know about the situation at the offsite center or the commanding officer’s decision to go to Koriyama. Alongside five other hospital and retirement home staff and 11 officers from Futaba Police Station, including police chief Masami Watanabe, Suzuki kept up his vigil at the hospital throughout the afternoon and evening.

March 14, 8 – 10 p.m.: “She kept rolling through the hospital in a wheelchair”

Nightfall on March 14 brought neither the return of the commanding officer nor other SDF rescuers.

Suzuki and the other staff had been forgoing sleep to care for patients and drive to neighboring towns to search for help. It had been three days since the disaster began, and they were at the limits of exhaustion.

Suzuki sent two of the hospital staff home to get some rest, and told the Deauville Futaba director and office head to sleep at their now-evacuated facility. But Suzuki himself continued to care for patients, alongside a senior male doctor.

At 8 p.m., Futaba Deputy Police Chief Akimasa Nitta arrived at the hospital to relieve Chief Watanabe. As per prefectural police policy, the chief was responsible for the whole district in the event of a disaster; he couldn’t just stay to help at the hospital.

Nitta sent three of the police officers back with Watanabe, keeping with him at the hospital seven of the strong, younger ones.

He lost no time presenting himself to Suzuki: “I’ve come to take charge of the police at the hospital.”

“The SDF commanding officer took the Deauville office head’s car and hasn’t come back,” Suzuki told him, venting his frustration.

Nitta, having just arrived, didn’t fully grasp what Suzuki was saying. “The car’s not that important right now, is it?” he replied, trying to sooth the exhausted doctor.

Leaving Suzuki, Nitta went to check on the patients.

“To my untrained eye, it was hard to tell whether they were living or dead,” he recalled at a hearing at the Fukushima public prosecutor’s office on Nov. 30, 2012. “The hospital director continued treating them, replacing their IVs and such, by flashlight.

“It seemed like there were also a number of patients with mental illnesses. They could move around some. There was this one elderly woman — maybe she had dementia — who kept rolling through the hospital in a wheelchair, shouting.”

March 14, 10 p.m. – March 15, 12 a.m.: “I’m not leaving while there are patients here”

A little past 10 p.m., two hours after Nitta had arrived at the hospital, he received a message via his transceiver from the Futaba Police Station’s emergency response headquarters in Kawauchi village. Following the hydrogen explosions at Fukushima No. 1, everyone at Futaba Police Station, based in the town of Tomioka, had evacuated to Kawauchi, 25 kilometers southwest of Futaba Hospital.

“The unit 2 reactor seems to be melting down. It’s too dangerous to stay near the nuclear plant — evacuate immediately. A withdrawal has already been ordered on the firefighters’ radio.”

With Fukushima No. 1’s cooling systems still offline, the nuclear fuel in unit 2 was overheating and had begun pooling in the bottom of the reactor. A meltdown could potentially release much more radiation than the hydrogen explosions up until that point. The police had decided that everyone remaining near the plant must evacuate.

Nitta quickly explained the situation to Suzuki. “We should evacuate, at least for a while.”

Suzuki refused. “I’m not leaving while there are patients here.”

Nitta tried to reason with him. “It’s an emergency. We can come back once we know it’s safe. Will the patients be in trouble if you leave them for a bit?”

“They should be ok,” Suzuki conceded. “I’ve completed their treatment for now.”

Nitta played his ace. “Who will look after the patients if something happens to you?”

Suzuki finally relented.

Following Nitta’s instruction, Suzuki and the other doctor remaining at Futaba Hospital evacuated in a police car to Wariyama Tunnel, about 20 kilometers southwest. They chose the tunnel because it was both close to the police’s emergency response headquarters in Kawauchi and not too far from Futaba Hospital. They could return quickly when able, and in the meantime the tunnel might provide some cover from radiation blown from Fukushima No. 1.

Soon after arriving at Wariyama Tunnel, another order came through the police transceiver, this time from the Fukushima Prefectural Police’s disaster response headquarters: “We are unable to confirm that the nuclear plant is in critical condition. Return to Futaba Hospital.”

But on their way back, a worrying message came through the wireless from police officers in Okuma town.

“About 100 vehicles, including passenger cars, just raced past on Route 288 toward Koriyama.”

National Route 288 connected Okuma, the town containing Fukushima No. 1, with Koriyama city, 70 kilometers to the west.

“Were these vehicles coming from the plant?” Nitta wondered, concerned.

As they approached the Okuma town hall, located five kilometers from Fukushima No. 1, Nitta noticed something amiss.

When they had passed town hall on their way out of Okuma, a number of SDF vehicles had been parked outside. But now, not a single one remained. Oil drums, used to carry gas for the SDF vehicles, were scattered about. They were still full.

“Something serious must have happened,” Nitta thought. “Fukushima No. 1 must be in such bad shape that the SDF left their gas behind in their rush to escape.”

He decided it was best for them to go back to Wariyama Tunnel, against the orders from the prefectural police’s disaster response headquarters.

A road in Okuma town ruptured by the magnitude 9 earthquake. Photo taken on March 18, 2012 by Shinshu Hida. (C) Shinshu Hida

On his transceiver, Nitta informed Futaba Police Chief Watanabe that the SDF had beat a quick retreat from the area surrounding the plant and that they themselves were heading back to the tunnel. Watanabe assented.

Suzuki asked Nitta to pick up the Deauville Futaba director and office head, who were resting at their now-empty facility. He roused his colleagues, and the group headed back to Wariyama Tunnel, arriving around midnight on March 15.

Bereft of staff, police, and the SDF, Futaba Hospital now simply housed 92 patients and three corpses.

March 11, 5 p.m. – March 12, morning: Offsite center in the dark

One more group of responders was preparing to evacuate Okuma as the situation at Fukushima No. 1 worsened on March 14: the offsite center.

Located five kilometers from the plant, the offsite center had originally been built to function as a local emergency response center in the event of a nuclear accident at Fukushima No. 1 — the “site” its name referred to. One of the center’s responsibilities was to coordinate the evacuation of residents in the surrounding municipalities during an accident.

But when disaster actually struck, it proved impossible for the offsite center to function as planned.

At 5 p.m. on March 11, about two hours after the earthquake, the emergency disaster response headquarters set up at the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry offices in Tokyo dispatched Vice Minister of the Economy Motohisa Ikeda to lead the offsite center. He arrived at 12 a.m. on March 12 following a journey by car and helicopter.

But the center was pitch black. The earthquake had caused a power outage, and the backup generators weren’t working.

Ikeda went first to the neighboring Environmental Radioactivity Monitoring Center, which had power. A prefectural institution, the monitoring center’s usual role was to conduct PR activities related to nuclear power and to measure radiation.

Fukushima Vice Governor Masao Uchibori and a few others were already at the monitoring center, but it wasn’t a large team.

At 1 a.m. on March 12, power was finally restored to the offsite center, and Ikeda, Uchibori, and the others moved there. By morning, the center had gradually become fully staffed with roughly 150 police, SDF members, and prefectural and TEPCO employees, including TEPCO Vice President Sakae Muto.

It had been 18 hours since the disaster began.

The offsite center in Okuma town. The building has since been demolished. Photo taken on March 27, 2014 by Shinshu Hida. (C) Shinshu Hida

March 12–13: Number of patients incorrectly reported

At 6 a.m. on March 12, the offsite center received a call from the ministry of the economy’s emergency headquarters: “The prime minister has ordered the evacuation of all residents within a 10-kilometer radius of Fukushima No. 1.”

Overseeing this complex task was Yoshihiro Takada, head of citizens’ affairs in the Fukushima prefectural government. His role at the offsite center was head of residents’ safety — in other words, to evacuate residents in coordination with municipal employees from Okuma and other neighboring towns.

But accurate and comprehensive information on locals’ evacuation status proved difficult to come by. In theory, employees from neighboring municipalities were supposed to gather at the offsite center and share information. But faced with a triple disaster, the municipalities had their hands full, and in many cases staff simply didn’t show. Takada rang various town halls, but often the lines were busy and he couldn’t get through.

Although Futaba Hospital was only a kilometer away from the offsite center, Takada had only a patchy understanding of the situation there.

At 2 p.m. on March 12, the first group of buses carrying 209 patients departed the hospital, with 129 at Futaba Hospital and 98 at Deauville Futaba still left behind.

The fact that patients still needed to be evacuated was reported at a general meeting held at the offsite center at 1 p.m. on March 13. However, the number of patients reported — “81 at Futaba Hospital, 100 at Deauville Futaba; to be evacuated on SDF buses” — was incorrect, 46 lower than the reality.

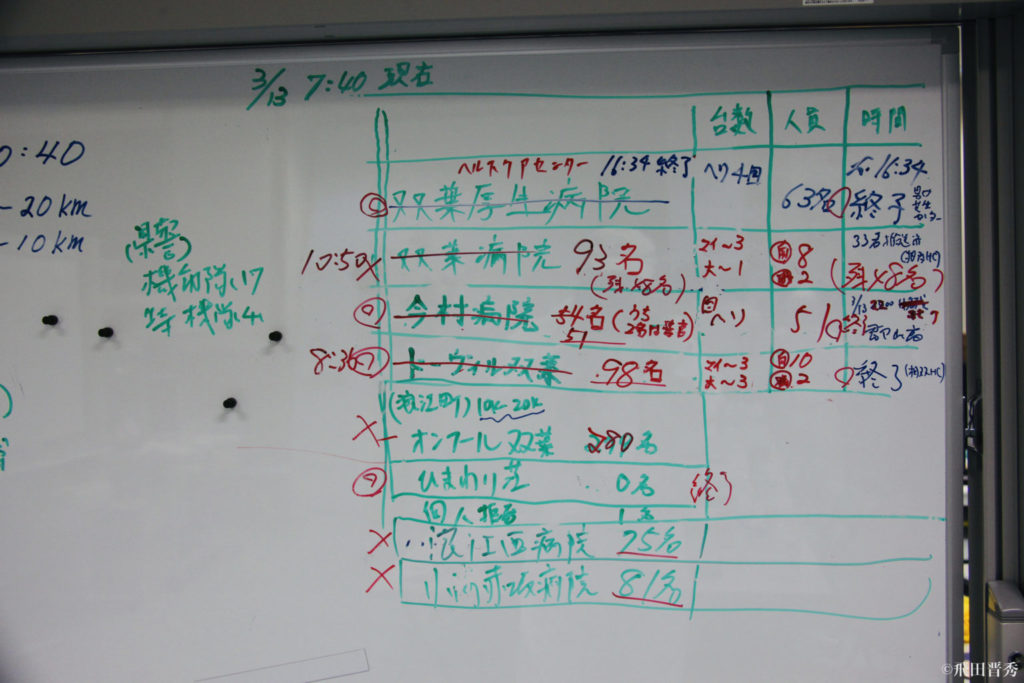

A whiteboard left behind at the offsite center. The number of patients at Futaba Hospital listed is incorrect. Photo taken on June 20, 2014 by Shinshu Hida. (C) Shinshu Hida

March 14, morning – March 15, 9 a.m.: “Quite a number of them had fled”

On the morning of March 14, the unit from the SDF’s 12th brigade evacuated 132 patients from Futaba Hospital and Deauville Futaba, but their buses didn’t have room for more. With 92 patients still awaiting rescue, those at the hospital assumed more help was coming.

But by then, the offsite center was beginning to feel like they needed rescuing themselves.

Radiation levels at the center were rapidly climbing. Outdoor readings had reached 800 microsieverts per hour, and even inside the building readings were in the tens of microsieverts. After the accident, municipalities in Fukushima and elsewhere set their decontamination goal to 0.23 microsieverts per hour or less. Those working in the offsite center were being exposed to 100 times that amount; outside, it was over 3,000 times as high.

Dread was building in Takada, the evacuation coordinator. He worried that staying much longer would be fatal.

Around 6 p.m. on March 14, a TEPCO employee working at the offsite center ran to deliver a memo to Vice Minister Ikeda — a prediction of how the situation would progress at the nuclear plant’s unit 2.

“18:22: Fuel exposed. 20:22: Reactor core meltdown. 22:22: Containment vessel damaged.”

Meltdown was almost upon them.

At 7:20 p.m., the offsite center leadership — high-level officials from the government, SDF, and TEPCO — gathered for an emergency meeting to consider evacuating the center.

At a general meeting held immediately after, it was decided that the offsite team would relocate to the Fukushima Prefectural Office. Vice governor Uchibori and some of the staff would go first to prepare a room in the prefectural office with the necessary videoconference system and desks. Uchibori’s group arrived at the prefectural office at 12:10 a.m. on March 15.

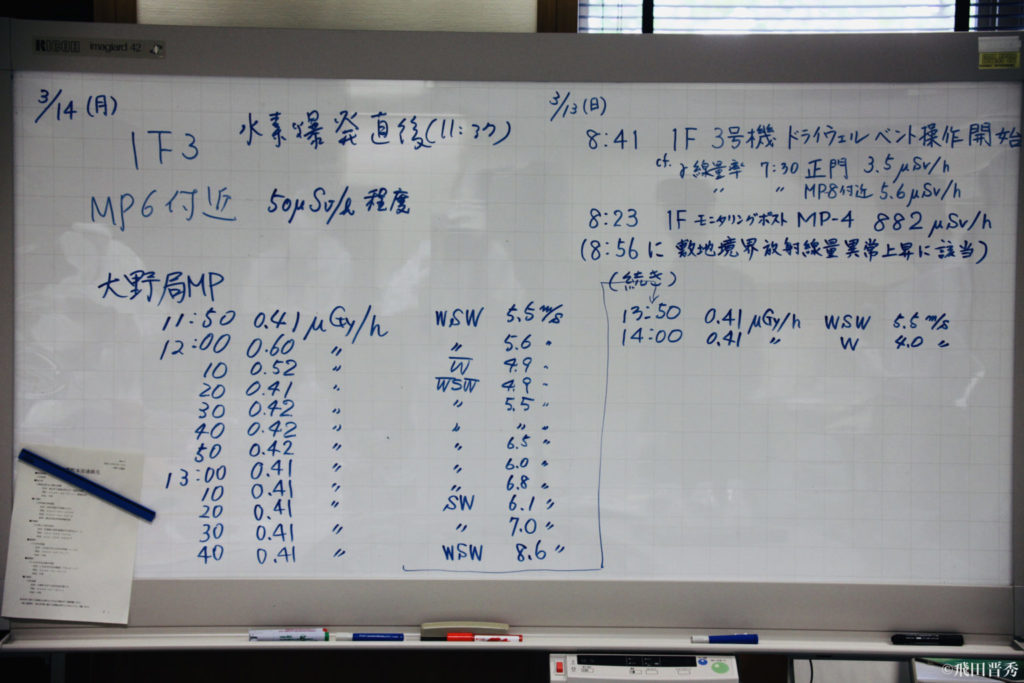

A whiteboard left in the offsite center records the radiation levels near Fukushima No. 1. Photo taken on June 20, 2014 by Shinshu Hida. (C) Shinshu Hida

One task remaining to those still at the offsite center was to confirm the evacuation of all residents. Ikeda called another general meeting.

“The captain is last to leave a sinking ship,” he emphasized. “There is no way we are leaving before each and every resident is evacuated.”

Takada, who, as head of residents’ safety, had remained at the offsite center, realized that the room was looking particularly empty.

“Although it had been decided that about 100 of us would remain at the offsite center, somehow we were down to about 50,” he testified on Feb. 27, 2012 for the government’s Accident Investigation Committee. “I remember thinking that quite a number of them had fled.”

Takada wondered what had happened to the patients at Futaba Hospital. Around 7:30 a.m. on March 15, he went to check on the hospital with a police officer who had been at the offsite center.

There were no doctors or nurses. The bedridden patients lay where their beds had been gathered in a large, open room. Patients in wheelchairs simply sat still, unmoving.

The SDF arrived at 9 a.m. Takada helped them evacuate the patients.

The captain of the sinking ship: “Maybe the hospital didn’t do enough to ask for help”

At 11:26 a.m. on March 15, all remaining staff left the offsite center. The SDF’s evacuation of Futaba Hospital, however, would take another 12 hours, finally finishing in the early hours of March 16.

Ikeda, who led the response at the offsite center, has since retired from politics. Tansa asked to interview him about the handling of the Futaba Hospital evacuation.

Although the interview lasted two hours, Ikeda spent the majority of the time speaking about other subjects, only touching on Futaba Hospital for roughly 10 minutes.

We asked his view on the deaths of six patients during transit to the evacuation center.

“The Futaba Hospital case really needs looking into, doesn’t it?” Ikeda replied. “I didn’t hear this directly, but it seems the evacuation center was really far away. It must have been a horrible journey in those buses. Why did they go all that way?

“If someone with common sense, like maybe those driving the buses, had been there, maybe they wouldn’t have been subjected to such a long journey.”

We asked Ikeda for this thoughts on the hospital’s handling of the situation. Its desperate staff had tried again and again to secure assistance from Okuma town hall, the SDF, and police.

“Maybe the hospital didn’t do enough to ask for help,” Ikeda pondered.

To be continued.

(Compiled from articles originally published in Japanese on March 12 and 15, 2021. Translation by Annelise Giseburt.)

Abandoned at Futaba Hospital: All articles

Newsletter signup

Newsletter signup