“Some patients are bedridden” — misinformation impeded rescue mission (3)

2021.03.23 13:07 Nanami Nakagawa

Wheelchairs in front of Futaba Hospital left untouched since the evacuation. Photo taken on March 18, 2012 by Shinshu Hida. (C) Shinshu Hida

Midnight on March 14, 2011. At last equipped with hazmat suits, a unit from the Self-Defense Forces’ 12th brigade departed Camp Koriyama to rescue the 277 patients and residents who had been left behind at Futaba Hospital and retirement home Deauville Futaba as the area surrounding the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant was evacuated.

Although the unit, then sans hazmat suits, had attempted the journey once before, at 3 p.m. on March 12, a hydrogen explosion at the damaged plant’s unit 1 had prompted them to return to Koriyama for proper gear.

Twenty-seven hours later, the rescue mission finally began its second attempt.

March 14, 4 – 10:30 a.m.: Skin and bones

The 12th brigade unit charged with the evacuation of Futaba Hospital had received the following orders from its command center.

“The evacuation of Futaba Hospital and Deauville Futaba are top priority. Transport the evacuees to the Soso Public Health and Welfare Office for radiation screening before continuing to the evacuation site, Iwaki Koyo High School. There are still 98 patients at Futaba Hospital and 120 residents at Deauville Futaba. Some patients are bedridden; take care when moving them.”

The SDF’s numbers were wrong: In reality, there were 129 patients at Futaba Hospital and 98 residents at Deauville Futaba. But it was the phrase “some patients are bedridden” that would prove the biggest impediment to the rescue mission.

Based on the information he was given, the commanding officer decided to bring three large buses and six minibuses.

“These nine vehicles can carry about 300 people, and we can use seats without armrests for the bedridden patients,” he calculated. “We should be able to get everyone out with a maximum of two trips between Futaba Hospital and the radiation screening site.”

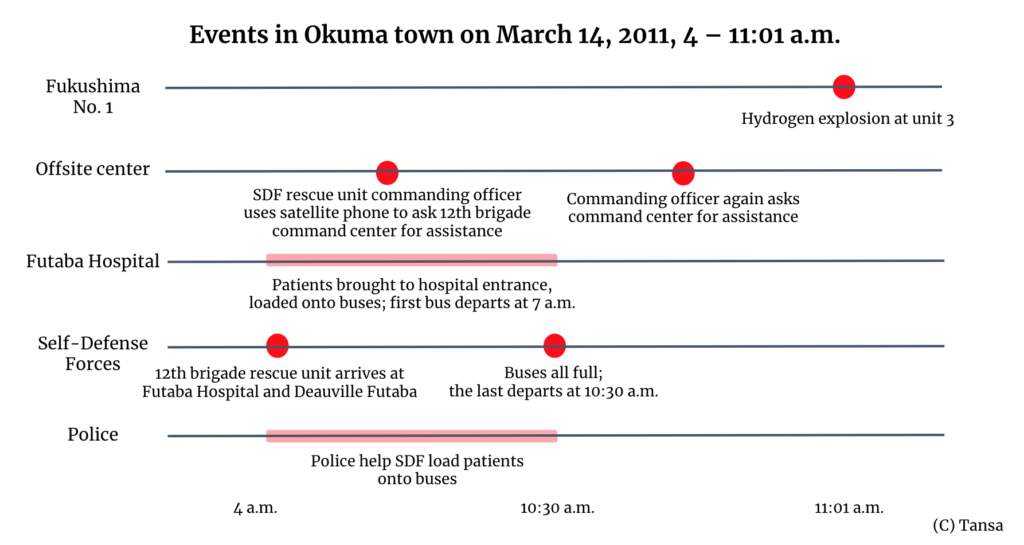

At 4 a.m. on March 14, the unit arrived at Futaba Hospital.

The commanding officer went first to Deauville Futaba — and was horrified when he opened the door to the hall where the elderly residents had been gathered. Dozens lay on beds blanketing the hall floor. The stink of human waste filled the room.

“Are you alright?” he called out to the residents.

“The SDF has come for us!” they exclaimed in relief.

Leaving the Deauville residents to his subordinates, the commanding officer next went to the nearby Futaba Hospital. He spoke with hospital director Ichiro Suzuki in the hospital office.

“Almost all of the patients are bedridden,” Suzuki told him. “There are even some with terminal cancer.”

The commanding officer was shocked: He had only heard from the brigade’s command center that “some” patients were bedridden.

“Please don’t transport the patients in an upright position,” Suzuki continued. “They should be lying down.”

Each bedridden patient would take up multiple seats on the buses.

The commanding officer had calculated that the three large buses and six minibuses could carry about 300 — sitting upright. But with so many bedridden patients, he was no longer sure his vehicles would be enough for all 227 needing rescue.

The SDF began loading patients onto the buses.

A dozen or so officers from Futaba Police Station dressed in hazmat suits had also arrived at the hospital to assist the evacuation. They had brought more hazmat suits with them, which they attempted to get the patients into: When the patients were moved from the hospital building to the buses, they would be exposed to the open, radioactive air.

“They’ll only be exposed for a moment,” said the SDF commanding officer, who had previous experience in the forces’ chemical unit. “Getting them into protective gear will only delay the rescue operation and further weaken the patients. Just get them onto the buses quickly.”

Suzuki agreed, thinking the commanding officer was quite shrewd despite his youth. The officer was a second lieutenant; if he had enlisted right out of university, he probably would be in his mid-20s.

They started evacuating patients from the hospital’s first floor. Suzuki removed their IVs, and the SDF and police officers conveyed them to the hospital entrance on stretchers. From there, SDF officers lifted them onto the buses. The patients were just skin and bones; a single officer could easily carry one on his own.

A row of bags containing soil contaminated by radiation in Okuma town. Photo taken on March 2, 2021 by Makoto Watanabe. (C) Tansa

March 14, 10:30 – 11:01 a.m.: “Why have you stopped?”

Following Suzuki’s instructions not to have the bedridden patients sit upright, the officers laid them down using the buses’ auxiliary seats. Although, under normal conditions, five people could be seated per row, now each row only had space for two. The buses filled quickly.

Realizing they wouldn’t be able to evacuate everyone, the commanding officer tried to contact the 12th brigade’s command center, but his radio couldn’t receive any signal in the area around Futaba Hospital.

He asked a police officer for a ride to the offsite center to use its satellite phone. The center, led by the vice minister of the economy and staffed by TEPCO and Fukushima Prefecture employees, was used to coordinate the accident response from a location relatively close to the plant.

“Almost all the Futaba Hospital patients and Deauville Futaba residents are bedridden,” the commanding officer explained over the phone. “There are barely any staff; we don’t have enough people or vehicles for the evacuation. And we need a medical unit.”

Having delivered his message, he returned immediately to Futaba Hospital to continue the evacuation.

The last of the nine buses was full by 10:30 a.m. Although all 98 Deauville Futaba residents had been loaded onto the buses, 92 patients still remained in Futaba Hospital, in addition to the three who had already passed away.

“That’s it for now,” the commanding officer ordered.

Suzuki didn’t realize the buses were full. “Why’re you stopping?” he objected. “There are still so many patients left.”

“There’s no more room,” the commanding officer explained. “We’ll come back soon for everyone else.”

The 12th brigade command center’s misinformation that there were only “some” bedridden patients had caused the rescue unit to be woefully unprepared.

Although he ordered the last of the nine buses to leave for the Soso health office, the commanding officer stayed behind. The first bus had departed at 7 a.m., and he imagined that by now it would be returning to Futaba Hospital after dropping off the patients.

He made another report to the 12th brigade command center via the offsite center’s satellite phone: “We will continue working with the police to complete the evacuation. The buses will shuttle back and forth between the Soso health office and the hospital. The first bus should have returned by now, but it hasn’t; it’s clear that the shuttle operation will take time. Please send assistance, including a medical unit.”

Around 15 minutes later, at 11:01 a.m., the commanding officer heard a violent explosion. Looking east, he saw white smoke rising from Fukushima No. 1.

March 14, 11:20 a.m. – 4 p.m.: Locked out of the offsite center

At this point, the following people remained at Futaba Hospital, in addition to 92 patients and three corpses: hospital director Suzuki, the Deauville Futaba director and office head, three hospital staff who had returned to help, about a dozen officers from Futaba Police Station, and the SDF unit’s commanding officer.

Despite the commanding officer’s requests for help, none had arrived by 11:20 a.m. Without working land lines, cell phones, or radios, Futaba Hospital was cut off from the world.

The commanding officer decided to once again call for help using the offsite center’s satellite phone. But the police had disappeared somewhere following the 11:01 a.m. explosion at Fukushima No. 1; there was no one to give him a ride.

“I’m going to go request help. Can I borrow your car?” he asked Suzuki.

In the end, the Deauville Futaba office head offered his, and the commanding officer drove off.

But as he approached the offsite center, he noticed something had changed.

All of the building’s windows and doors had been shut tight and the gaps sealed with tape.

“Please, let me use your satellite phone,” the commanding officer begged through the door.

But the staff member on the other side of the glass refused. “Wait inside your car. You’ll be exposed to radiation out in the open!”

No matter how many times he asked, the answer was the same. The commanding officer returned to his car.

A little while later, figures in camo approached from behind — two SDF officers carrying a third, who was wounded and seemed unable to walk on his own.

The officers shouted through the door to be let in. The commanding officer could understand what they said even from inside his car. But the person on the other side of the glass shook their head.

“If they won’t let in someone too weak to walk, there’s no way they’re letting me in,” the commanding officer thought.

A radiation counter at the former Okuma town hall. Photo taken on March 2, 2021 by Makoto Watanabe. (C) Tansa

He gave up on the idea of using the offsite center’s phone. Tearing off a page of notebook paper, he wrote: “Please inform the 12th brigade that there are 90 patients and six staff left at Futaba Hospital.”

The commanding officer stuck the note to the glass door so that those inside could see and returned to his car.

He had promised Suzuki that he would return to the hospital. But without being able to directly contact the command center, he thought it would be faster to return to Camp Koriyama and urge them to send more assistance.

The commanding officer arrived at Koriyama at 4 p.m. and gave his report to the officers assembled at the command center, including the head of the brigade.

“In addition to being told the wrong number of patients, almost all were bedridden. The hospital has two separate wards that house patients; those in the second still haven’t been evacuated.”

“Don’t worry, units from Tohoku and Kanto are coming with ambulances to complete the evacuation,” replied the brigade leadership.

It wasn’t until later that the commanding officer realized how wrong his superiors had been.

March 14, 12 p.m. – March 15, dawn: “These were corpses”

Although the commanding officer had imaged that the buses would return to Futaba Hospital after dropping off the patients for radiation screening at the Soso health office, the caravan instead continued on to its final destination.

The buses were bound for Iwaki Koyo High School, located 45 kilometers south of Futaba Hospital in Iwaki city. But the Soso health office was in Minamisoma city, 40 kilometers north of the hospital — the opposite direction. The entire journey would ultimately take almost 10 hours.

Route traveled by the second group of buses that evacuated Futaba Hospital. It took 230 kilometers and almost 10 hours to finally reach the evacuation center.

The last bus from Futaba Hospital arrived at the Soso health office at noon. But screening the bedridden patients for radioactive materials was slow going. The medical office head, who could see that the patients were getting weaker and weaker, eventually told all the buses to proceed to the evacuation center in Iwaki without completing the screenings.

They departed for Iwaki at 3 p.m.; it had already been four and a half hours since the last bus left the hospital. Iwaki Koyo High School was 85 kilometers directly south of the Soso health office, but by then the evacuation zone around Fukushima No. 1 had been extended to 20 kilometers — they would have to made a detour. In the end, the buses drove over 200 kilometers, on roads damaged by the earthquake and tsunami.

The Iwaki Koyo High School principal, Masa’aki Tashiro, was shocked by the scene that greeted him when the buses finally arrived at 8 p.m. A foul smell filled the vehicles. Patients had fallen from their seats onto the floor. In some cases, their diapers had slipped out of place, leaving them smeared in their own excrement.

Principal Tashiro had already informed his counterparts in the Fukushima prefectural government that the school had no medical facilities. Without being told the patients’ condition, he had assumed that they were mostly from Futaba Hospital’s psychiatric ward and that they were in relatively good physical health.

There was no way the school could care for these patients on its own. Tashiro said they would not be able to take them in without medical staff on hand.

The buses set off again, this time for Iwaki Kaisei Hospital, a 10-minute drive away.

Iwaki Koyo High School. Photo taken on Feb. 23, 2021 by Nanami Nakagawa. (C) Tansa

A psychiatric hospital that was part of the same conglomerate as Futaba Hospital and Deauville Futaba, Iwaki Kaisei had already taken in the first group of over 200 evacuees from Futaba Hospital and Deauville Futaba on March 12. Its wards were full to bursting. Even with patients lying two to a bed, there still weren’t enough; some patients had simply been laid down on the hallway floor. There was no way the hospital could take in anyone else.

The buses went back to Iwaki Koyo High School. Tashiro had told them that the school would take the patients if the hospital dispatched medical professionals to care for them. The doctors, nurses, and other staff who had evacuated Futaba Hospital on March 12 were also at Iwaki Kaisei; five of them agreed to go attend the second group.

Upon arriving at the school, the medical team first checked the patients before bringing them off the buses. They first found that three had died on the journey.

The deputy director of Futaba Hospital’s nursing department, who was among the five attending the second group of patients, testified as a witness on Sept. 18, 2018 at a criminal trial regarding the patients’ deaths.

“The first big shock was that, as soon as the bus door opened, there was just this horrible stench,” she recalled.

“The second was the faces of the dead. It was clear that they had died on the journey, their bodies growing stiff where they lay. They were so pale. It wasn’t as though life had just left them — these were corpses.”

The patients hadn’t had anything to eat or drink during their 10-hour journey. Even the living were suffering from hypothermia and dehydration: Their faces had sickly complexions, and their hands and feet were cold. The medical team picked up rice balls and tea from the school’s conference room to feed the patients.

By the time they had all been carried into the school gym, in the early hours of March 15, another three were found to have passed away on the journey.

The doctor who confirmed their deaths was asked the following at the above-mentioned trial on Sept. 19, 2018.

“You’ve said that, at the time you departed Futaba Hospital [at 2 p.m. on March 12], none of the patients were in critical condition or seemed near death, is that right?”

The doctor’s response was brief.

“That’s correct.”

To be continued.

(Compiled from articles originally published in Japanese on March 10 and 11, 2021. Translation by Annelise Giseburt.)

Abandoned at Futaba Hospital: All articles

Newsletter signup

Newsletter signup