Atago Bridge over Hirose River at dusk on October 28, 2017

Junko Iizuka was forcibly sterilized over half a century ago, without a word of explanation. She was 16 years old.

Junko Iizuka is not her real name. In fact, it’s the name of a teacher who was kind to her when she was small. She began using the pseudonym to avoid harassment, which began when she started to share her story.

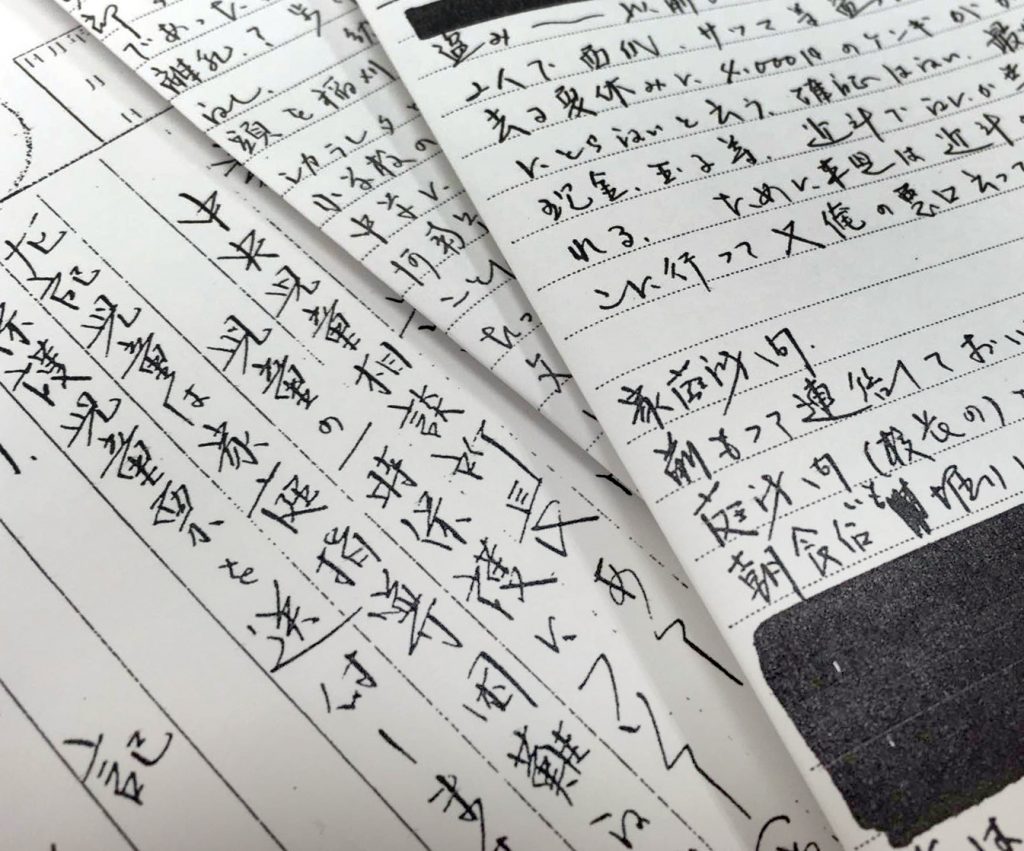

Now 77, Junko lives alone in a two-bedroom public housing apartment in Sendai, the largest city in Japan’s Tohoku region. When we visited her on August 30, 2017, she dragged two cardboard boxes out of her bedroom. They were stuffed full of documents about Japan’s forced sterilization program. Some she had obtained through freedom of information requests: records and minutes of her negotiations with government organization, booklets by her support groups, newspaper clippings, letters, and faxed documents. Among them was a 12-page account of her life, written by Junko herself.

“I wanted to know what they had done to me. I needed to keep writing, so that I wouldn’t forget it,” she explained.

Junko’s health has declined since she turned 65, and she suffers from asthma. She wakes early but often cannot get out of bed for lack of energy. Her building doesn’t have an elevator; if she goes out, she has to take the stairs.

At 69, Junko was diagnosed with cancer. She lost her hair and worries that she doesn’t know which day will be her last. But anger over her sterilization keeps her going: “My life was destroyed that day. I cannot die with regrets.”

Junko took us through the 12-page document chronicling how the government stripped away one of her basic human rights.

The “golden eggs” and the live-in maid

In 1961, Japan was buzzing with excitement for the upcoming 1964 Tokyo Olympics. Around the country, thousands of “golden eggs,” a term then used for promising youth, were heading to Tokyo to make their careers. Not Junko — though she too dreamed of life in the big city, she had no choice but to stay in Sendai.

Born in a small village near the city of Ishinomaki, Junko’s family was too poor to support her. She was put into an facility in Sendai just before her last year of junior high school, but she had to leave soon after when she turned 15, as her family had found her a job as a live-in maid.

Her new employers ran a real-estate business. The family had three children, with the eldest daughter the same age as Junko. Their situations, however, couldn’t have been more different. While the daughter always wore nice western-style dresses, Junko had to make do with monpe, Japanese work clothes. When the employer’s wife was in a bad mood, she took it out on Junko, verbally and physically abusing her.

One day, two years after she started working for the family, the wife spoke to Junko while she was taking a break.

“We’re going out. Get dressed.”

Until then, Junko had been so busy with work that she hadn’t had many opportunities to leave the house. Her one excursion was to the Osaki Yahata Shrine on New Year’s Day with the family. Even then, the wife always reminded Junko that she was a just maid and never let her shop, even while her own children did.

“Where are they taking me?” Junko wondered.

She had no choice but to go, so she changed into a floral dress and a pair of red vinyl shoes, the only possessions ever given to her by the family.

Crossing the Atago Bridge

Together with the family’s youngest daughter, the mother and Junko drove for about 20 minutes, crossing the Atago Bridge across the Hirose River south of Sendai. Junko had no idea where they were taking her. After crossing the bridge, they got out of the car and ate rice balls on a wooden bench.

A one-story building stood near some woods not far from their bench. A plaque in front read “clinic.” The meal finished, the mother took Junko inside the building.

To her surprise, Junko found her father waiting there. She hadn’t seen him in three years. The mother handed Junko over to her father and left the building with her daughter.

“Is something wrong with me?” Junko started to wonder. But she didn’t have a fever or feel any pain.

Pain in her belly

Junko next remembers finding herself lying in a bed. In hindsight, she thinks she might have been anesthetized, as she has no memory of how she got there. She was thirsty. But when she walked to the sink in the room to get a drink, a nurse stopped her.

“Let’s go home.” Junko left the clinic with her father. Her employer was long gone. They took the Sengoku train line and a bus back to Junko’s hometown.

Soon after they got home, Junko began to feel a sharp pain in her belly. It doubled her over; she squirmed in agony. It prevented her from sleeping at night. And it continued, month after month.

Although she remembered nothing, Junko started to suspect the pain was related to whatever had happened at the clinic.

Junko Iizuka talking to reporters at a press conference at the Sendai Bar Association on Jan. 30, 2018. She was wearing a pink scrunchy around her right wrist, a gift from the family of another victim of forced sterilization.

“Poverty village”

Junko was born in a village situated at the mouth of the Kitakami River, the biggest waterway in the Tohoku Region. About 50 families lived in the village, which was nestled between the river, mountains, and sea.

Though the sea was rich in seaweed and scallops, nobody in the village owned a fishing boat. People made a living grilling charcoal. In the winter, men went away looking work.

The chief priest of a local shrine told us that people had called it “poverty village.” When we visited, the area was still recovering from the 2011 tsunami. Weeds had returned much faster than the people.

Among the village’s 50 families, Junko’s was one of the poorest. Her father’s heath prevented him from taking constant work, and the family lived on welfare.

When she was a first grader at elementary school, her family’s wooden house burnt to the ground after the bare thatch of the mud walls caught fire. Junko remembers that they fled into a nearby bamboo grove, having managed only to save some bedding. In desperate poverty, the family was forced to live for a time in a relative’s barn, before moving to an old single-story house.

Her mother worked hard to support the family. She boiled warabi, a wild mountain plant, at night and went by bus to sell it in Ishinomaki City the next morning. When she returned home around noon, she worked in the fields and searched for more warabi.

Junko remembers her mother’s “messed up” eyes, unable to focus due to lack of sleep. Driven to exhaustion, she once tried to drown herself in the Kamikita River with Junko’s sister on her back. But she came to her senses and stopped herself when the child started to cry.

The eldest of three sisters and three brothers, even as a small child Junko realized she had to help take some of the burden from her mother’s shoulders.

When Junko returned home after three years of being away, she started working as a helper at a gynecological clinic. Her father found her the job. It wasn’t bad work: She liked taking care of people.

Yet the stabbing pain would always return, forcing her to miss work.

“Stop complaining!”

No one told Junko she had been sterilized, though her parents had always known.

But one day, she heard them speaking — a rare occasion, as they usually did not get along. “They sterilized her,” Junko heard her father say.

Junko was devastated to learn that she could never bear children. One day, her rage boiled over, and she confronted her mother, crying. But instead of comforting her, her mother just screamed back.

“When are you going to stop complaining?!”

This wasn’t the first time adults had made decisions about Junko’s life without her consent.

The contradictory case file

Years later, when she was 55, Junko used a freedom of information request to obtain her old case file from the Miyagi prefectural welfare office. It had been created when she was 14 years old. She needed to find out why she had been sterilized.

The documents shocked Junko.

“September 15, 1959: The local welfare commissioner came to the family home to talk about Junko. According to the commissioner, Junko and her aunt stole watermelons and yam from a nearby farm. People then began to accuse Junko whenever cash or other belongings went missing. Because of this, she became paranoid, yelling at neighbors when she assumed they were talking ill about her.

After the commissioner’s visit, an official from the welfare office interviewed the head of Junko’s junior high school and her teacher. Junko was reportedly violent and no one in her class paid her any attention. The dean said Junko was trying to behave better but he saw no improvement. The welfare official also interviewed Junko’s parents. Her father said Junko’s mother treated her daughter badly. Had she not, he said, things would’ve been different.”

“These are all lies,” says Junko. “We grew our own watermelon and yam every year, there was no need to steal.”

The welfare office commissioner had lived near Junko’s house. “Why did they have to lie?”

Something else also touched a nerve. Even if the welfare commissioner came with bad intentions, why did the official from the welfare office believe him without asking Junko herself?

Junko doesn’t remember speaking with the official. The records, however, say they did.

But she does remember returning home on a chilly autumn day, carrying a yam from the family’s field. The official and her father were talking. Junko briefly sat down in front of the official to say hello before heading into the kitchen.

The official later wrote in his records: “Clean in appearance compared to her mother; a bit on the thin side but looks healthy.”

He never asked Junko any questions.

Junko's case file, which she obtained from the Miyagi prefectural welfare office through a freedom of information request

“We ask for quick action”

Two months later, on November 10, 1959, the Ishinomaki welfare office sent a report titled “Temporary custody of a child” to the head of Miyagi’s central children consultation center.

“The child listed on the left is in a difficult family situation, so we ask for quick action,” it read. “The child listed on the left” was Junko. This sentence is what decided her fate.

In April 1960, five months after the report was written, Junko was forced to enter a new school for children with mental disabilities in Sendai. Komatsushima school had just opened that year; Junko’s was in its first class.

The previous school for children with mental disabilities, the only one in the prefecture, had been destroyed in a fire on December 11, 1956. Four wooden buildings, which at that time housed about 50 children, had burned down completely. An 11-year-old girl and boy, and a 16-year-old boy died in the blaze.

“I’m not sure how they ended up dead, but those three had the lowest IQs and couldn’t speak properly, so maybe they initially escaped then returned to the fire,” the principal speculated to the Asahi Shimbun newspaper at the time.

The prefecture took the fire as an opportunity to consider its handling of children with mental disabilities.

… To be continued.

(Complied from articles originally published in Japanese on Feb. 26, 27, 28, and March 1, 2018. Updated for readability on Feb. 18, 2021.)

Forced Sterilization: All articles

Newsletter signup

Newsletter signup