Prefectural review board decisions on forced sterilization “comparable with Nazis”

2018.06.11 17:54 Sayaka Kaji

Imagine if you were sterilized, your right to have children taken away forever, without your consent — perhaps even without your knowledge. That’s what happened to at least 16,500 individuals in Japan from 1948 until 1996.

Japan’s post-war Eugenic Protection Law, enacted in 1948, allowed prefectural review boards to decide to perform sterilization surgeries. Tansa obtained the minutes of board meetings held in all of Japan’s 47 prefectures.

Review board members included municipal leaders, executives of local medical associations, judges, and prosecutors. Vice governors, directors of prefectural health departments, district judges and prosecutors, heads of local police, medical professors, heads of prefectural medical associations, specialists, and caseworkers were also encouraged by the government to join the boards, according to a 1953 document.

Some review board members raised awkward questions about the system, with its echoes of Nazi eugenics, and pointed out that forced sterilization could constitute a violation of one’s basic human rights.

Nevertheless, all still went along with the system and voted to approve numerous sterilizations.

This article reveals how these review boards decided to perform sterilization surgeries. Many cases reveal a callous disregard for the lives of those being considered for the procedure.

Note: Documents obtained by Tansa include discriminatory expressions. In order to illustrate the situation fairly and accurately, we refrained from editing or censoring them.

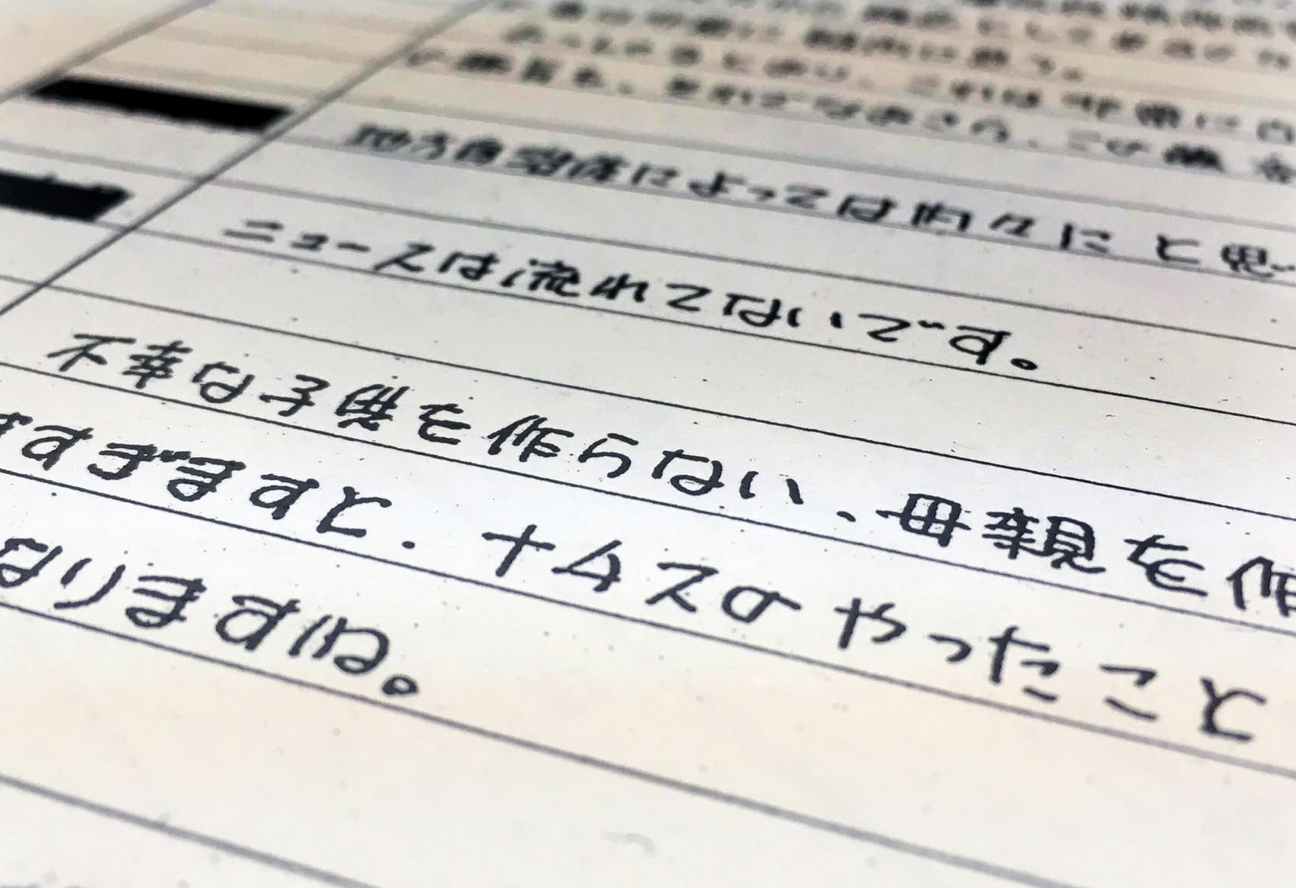

Documents gathered by Tansa to investigate Japan's forced sterilization program

“Wary of potential litigation”

On Dec. 10, 1969, the Yamaguchi Prefecture review board met to debate the forced sterilization of 14 people. During a discussion about the sterilization of a child with a mental disability, a committee member pointed out that the procedure could constitute a human rights violation. The document we obtained had blacked out the committee member’s name and affiliation.

“I worry we might be underestimating the gravity of issue from a humanitarian and human rights perspective,” they said. “I’m wary of potential litigation if this person gains more control over their life in the future.”

But in the end, the board voted for the procedure with “no objections,” including from the member who had initially expressed concern.

Ten years later, on March 12, 1979, the same board spent two hours discussing the cases of five people at a meeting held in the prefectural assembly building. One of the potential subjects was a woman suspected of having mental and physical disabilities; her physical mobility was limited to a crawl. A committee member challenged the case.

“I think it’s wrong for us to decide that one cannot bear children just because one is stupid — bearing children is a basic right that everybody is entitled to,” they said. “I’m not sure it’s right for us to make this decision for her.”

But once again, the board voted for sterilization without a single dissension.

The third case on the agenda that day was also considered to have a mental disability. Some board members questioned whether, given her disability, “anyone would think she had the mental capacity to decide whether she wanted a child.” Others suggested her family might support any children she had.

The forced sterilization program itself was questioned by one of the board members: “Much of the context of the Eugenic Protection Law rests on prewar concepts. It has many issues, including those related to human rights. I wonder how the national government sees these issues.

“If we go too far in saying that these surgeries should be used to limit the number of unfortunate children and mothers, some might compare this program to what the Nazis did. That could be problematic.”

Nobody objected when the case came to a vote.

Meeting minutes from the Yamaguchi Prefecture review board. A member expressed concern, citing similarities to the Nazis.

“Is preventing idiots from bearing children in the public interest?”

On Nov. 29, 1978, the Tottori Prefecture review board heard a case regarding a woman suspected of having a mental illness. The report was based on hearings conducted with the woman’s father and a teacher at her former junior high school.

Although she exhibited no symptoms when very young, as she grew up she often screamed and ran out of the house without shoes. Her memory appeared to worsen after beginning elementary school. In junior high school, her character became increasingly dependent, and she always stayed close to her teacher. After graduation, she changed jobs three times, never staying long. She helped with housework if asked but never volunteered to do so. Her doctor noted that “She requires some help and instruction in everyday life.”

Eight board members, including the chairman of the prefectural medical association, met at 2 p.m. that day to discuss the woman’s case.

A member of the prefectural government repeatedly said the decision should be made by considering whether “the surgery would serve the public interest by preventing hereditary diseases from spreading.”

Kozo Shuto, a deputy prosecutor and board member, asked for clarification: “Does your definition of ‘public interest’ include preventing idiots from bearing children?”

Meeting minutes did not record a single response to his question. The board members began discussing whether mental illness is hereditary.

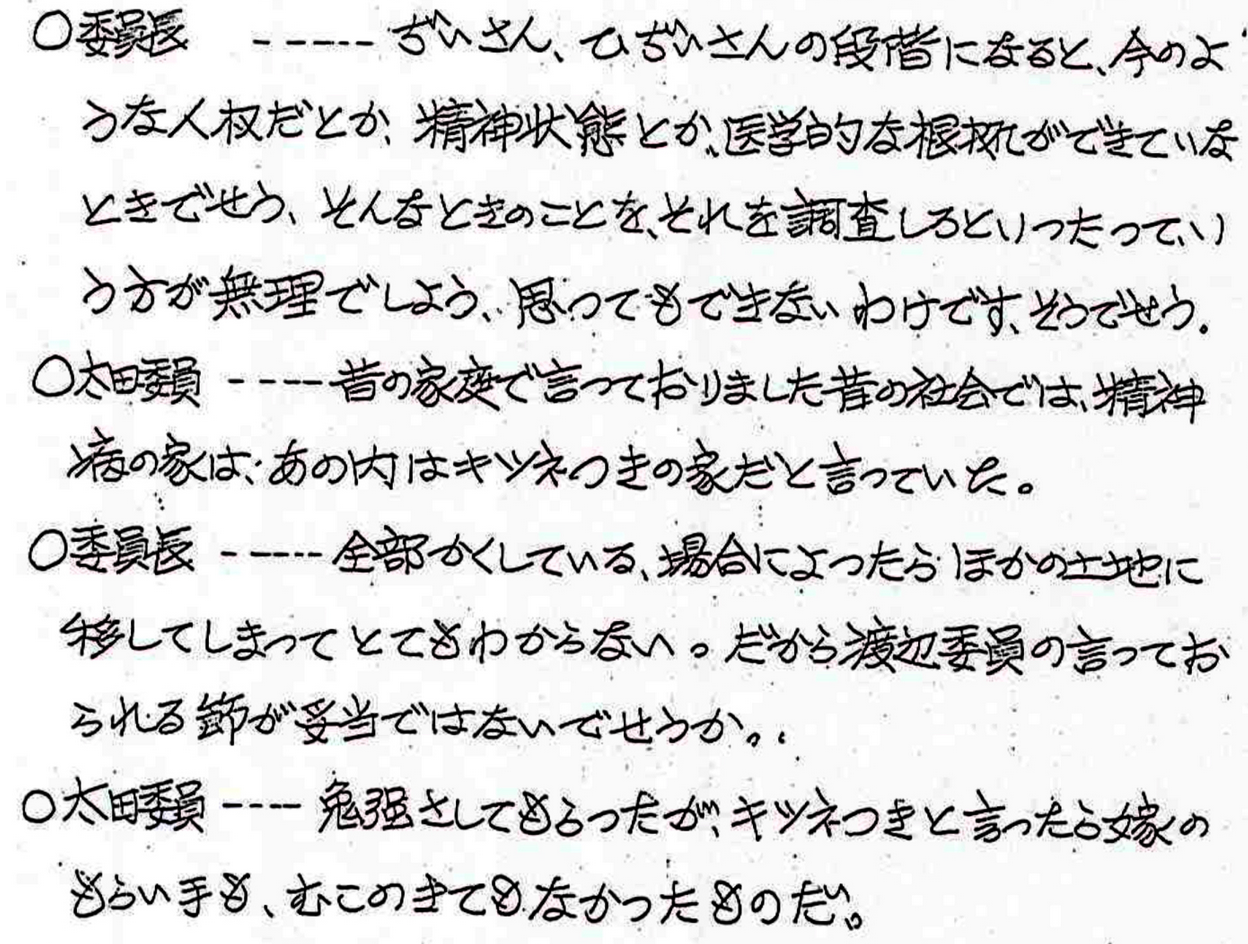

Meeting minutes from the Tottori Prefecture review board

“To say whether something is heredity is very complicated,” said psychiatrist Hajime Watanabe. “Looking at previous generations or even family trees can’t answer everything. We should to assume there’s a risk of mental illness if even one family member suffers from it, without being too scrupulous.”

“In the past, if a household had one family member with a mental illness, the family was said to be cursed. And their offspring had no marriage prospects,” said Jitsutaro Ohta, president of the prefectural social welfare council.

Then conversation shifted to the ability of women with mental disabilities to raise children.

“Even if she bears a child, she probably can’t raise it properly. It would be miserable growing up in such an environment,” said lawyer Masako Nakata.

“The father would be unknown; he may not acknowledge the child. There could be several potential fathers,” Watanabe rejoined.

“The child would be most miserable,” said Masuo Murae, chairman of the prefectural medical association and chair of the review board.

“That’s right,” Nakata affirmed.

“So we’re in agreement that the board will approve the procedure?” Murae asked.

Nobody objected.

In these men’s minds, the “public interest” would be undermined by a women with a mental disability bearing children.

Fate of two individuals decided within 20 minutes

The Chiba Prefecture board examined the cases of two individuals on July 1, 1958. The names and ages of the board members had been blacked out in the documents.

The meeting was convened at 1:30 p.m. After hearing a report on the first case, the board members voted in favor of sterilization without discussion or objection. The second case was similarly expedited.

The meeting adjourned at 1:50 p.m. following an announcement regarding which doctors would be conducting the surgeries. It took the Chiba board just 20 minutes to strip two women of their ability to bear children.

Fukuoka Prefecture decided on surgery without convening a meeting

On Jan. 28, 1982, an obstetrician in Fukuoka Prefecture reported the case of a 22-year-old woman with “hereditary mental retardation.” The diagnosis attached to the report was as follows.

Condition: Mental retardation

Progress of the condition: The subject has been mentally retarded since she was a child. She finished junior high school, where she was put in a special needs class. Her speech and language ability was severely underdeveloped. She easily gets tired of things and rarely sticks with anything. She has been repeatedly seduced and had multiple abortions, fathers unknown. She married in 1981 and bore a child, but it was put in foster care as she was incapable of raising it.

Current condition: She has an IQ of 45 and suffers from mild mental retardation. She is very childish and easily influenced by others, which makes it hard for her to have a normal adult life. The report said her father, mother, younger sister and aunt were suspected of suffering from mental retardation.

The Fukuoka Prefecture health department concluded that “sterilization surgery should be conducted as soon as possible.”

However, a review board meeting could not be held due to members’ conflicting schedules. So the prefecture asked board members to review the case file and make a decision without convening a meeting for discussion.

The board included the chairman of the prefectural medical association. Members were only required to write “approve” or “not approve,” without any justification for their decision. All approved.

Fukuoka Prefecture sterilized six without review sessions

According to Fukuoka Prefecture health department review board meeting minutes, six sterilizations were approved without a review board meeting. Members simply wrote in their decisions, according to documents from fiscal years 1980-81 obtained by Tansa.

In addition to the 22-year-old woman described above, the five others were women aged 39, 19 and 29, and men aged 22 and 27.

According to the documents, the health department “was not able to hold a review board meeting in a timely manner” regarding the case of the 39-year-old woman. And yet, the board took more than six months to make a decision via circulating and signing a report made by her doctor on Aug. 8, 1980.

Japanese government refused to offer redress

On July 12, 1953, the vice minister of health and labor sent out a notice to all prefectural governors reminding them that making decisions outside of board meetings wasn’t an appropriate procedure.

“The review should be conducted by board members at a meeting, rather than through passing around case files.

“On one hand, reviews need to be conducted in a timely manner, but, on the other, they require careful consideration. Therefore, prefectures should be careful not to make a sham of the system for the sake of expediting the process.”

In 1988, Japan rejected a UN recommendation that requested compensation for victims of forced sterilization. In a 2006 report, the government said the surgeries were conducted based on “a strict procedure of investigation.”

(Originally published in Japanese on Feb. 14, 2018. Updated on Feb. 6, 2021 for readability.)

Forced Sterilization: All articles

Newsletter signup

Newsletter signup