Japan’s prefectures competed for decades to sterilize people with disabilities, under instructions from the health ministry

2018.06.04 18:02 Sayaka Kaji

Key points

・The Japanese government conducted at least 16,500 forced sterilizations in a program that ran from 1948 until 1996, according to data compiled by Tansa. At least 2,390 of the victims were teenagers or children under 10 years old.

・Local governments competed to forcibly sterilize the most number of people, under pressure from the health ministry and the national government. They aggressively looked for individuals to be sterilized to respond to the national call. Kyoto Prefecture, for example, targeted mental hospitals and hospitals for disabled children.

・In February 2018, a woman in her 60s who says she was forcibly sterilized filed a damages lawsuit against the government. The woman says a prefectural eugenic protection review board in Miyagi Prefecture violated the constitution by ordering the sterilization at a local hospital in 1972. She was 15 and had a mental disability. She says she was given no explanation of her operation.

・The lawsuit is unlikely to be the last. Though calls have grown over the years for an investigation into the eugenics program, the government has made no response except to argue that the program was legal at the time. Similar programs in Germany and Sweden were quickly scrapped, and apologies and compensation were made to the victims there. Japan has yet to follow suit. Many records of Japan’s sterilization program have already been destroyed.

* * *

What would you do if someone important to you was sterilized, without them ever knowing it?

Three years after the end of World War II, Japan enacted the 1948 Eugenic Protection Law, which allowed the state to forcibly sterilize people with mental or intellectual disabilities. In 1996, the law was amended to become the Maternal Health Act, effectively banning involuntary sterilization.

In the intervening years, more than 16,500 people underwent forced surgery by the state, according to data compiled by Tansa. Some were not even told they would be unable to have children after the operation. Trickery and deception were widespread.

Article I of the law explained its purpose: to “prevent the birth of defective descendants.” The law originated in the postwar political ideology of “reviving the Japanese race.” It initially applied only to those deemed by the state to have hereditary genetic disorders and disabilities — such as schizophrenia, learning disabilities, manic depression, epilepsy, and hemophilia — but eventually people with non-hereditary genetic disorders and disabilities, and even some without any identified disability, were sterilized under the program.

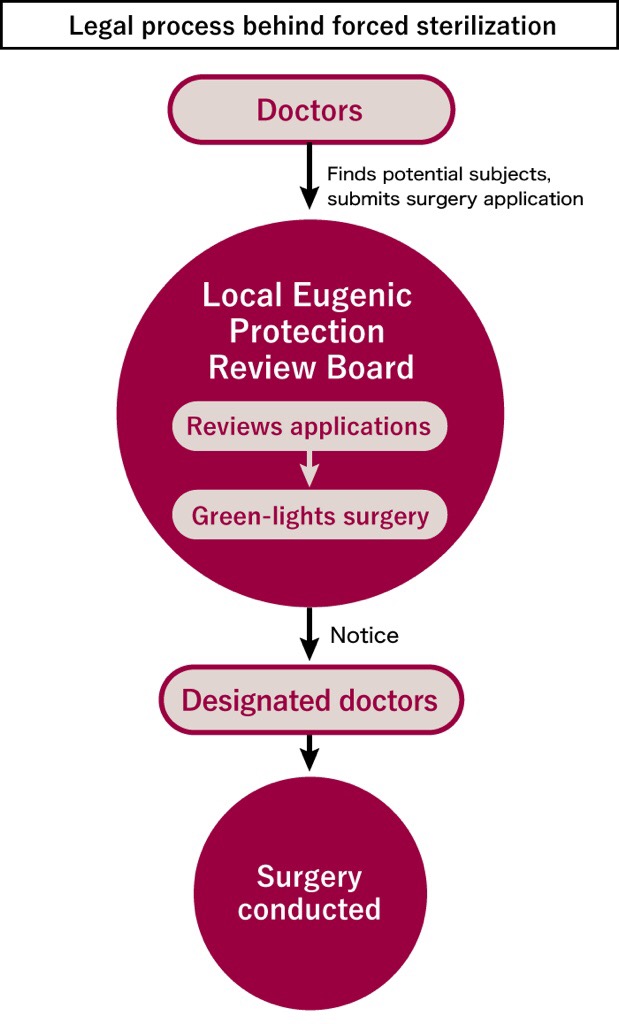

Surgeries were conducted regardless of whether these people consented, as long as permission came from local government review boards. Article 4 of the eugenics law said doctors were required to report to the review boards when they found a person with hereditary genetic disorders or disabilities.

Doctors were allowed to use anesthesia or physical restraints on individuals who were noncompliant, or even to deceive them, according to a notice sent to local governments by the health ministry on October 24th, 1949. In other words, if individuals refused to undergo sterilization surgery, doctors were permitted to drug, restrain, or trick them into having the operation. For men, the surgeries involved vasectomies; for women it involved tying the fallopian tubes to block ovum.

Many of the victims are still alive today, but the government has yet to offer compensation or an apology. In this investigative series, “Forced Sterilization,” we examine the government’s role in violating the human rights guaranteed by Japan’s constitution — in the name of “public good,” according to officials.

In August 2017, Tansa began obtaining documents via freedom of information requests from all 47 Japanese prefectures, national archives, and the National Diet Library. These documents shed a harsh light on the forced sterilization program. We begin our series by looking at how municipalities competed to increase the number of forced sterilization surgeries, in accordance with the national government agenda.

So far, just one victim has spoken publicly about her experience, in an attempt to hold the national and local governments accountable. “Junko” is unable to use her real name in fear of backlash. Now her many years of advocacy is finally being heard, even by the government.

In this series, we will share Junko’s story and the crimes against humanity that it represents. We start our investigation by examining the system the government created to pursue and impose forced sterilizations.

Note: Documents obtained by Tansa include discriminatory expressions. In order to illustrate the situation fairly and accurately, we refrained from editing or censoring them.

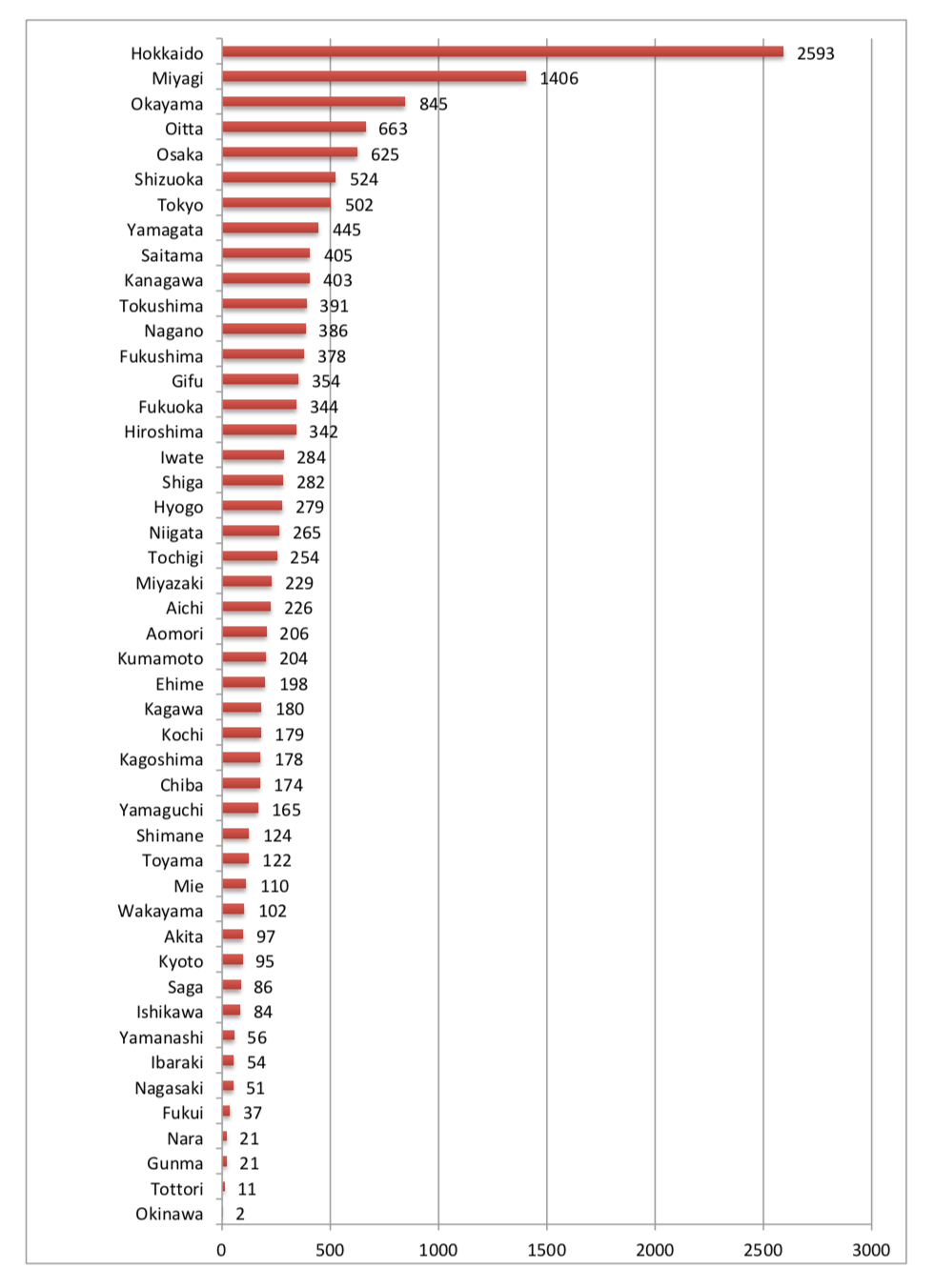

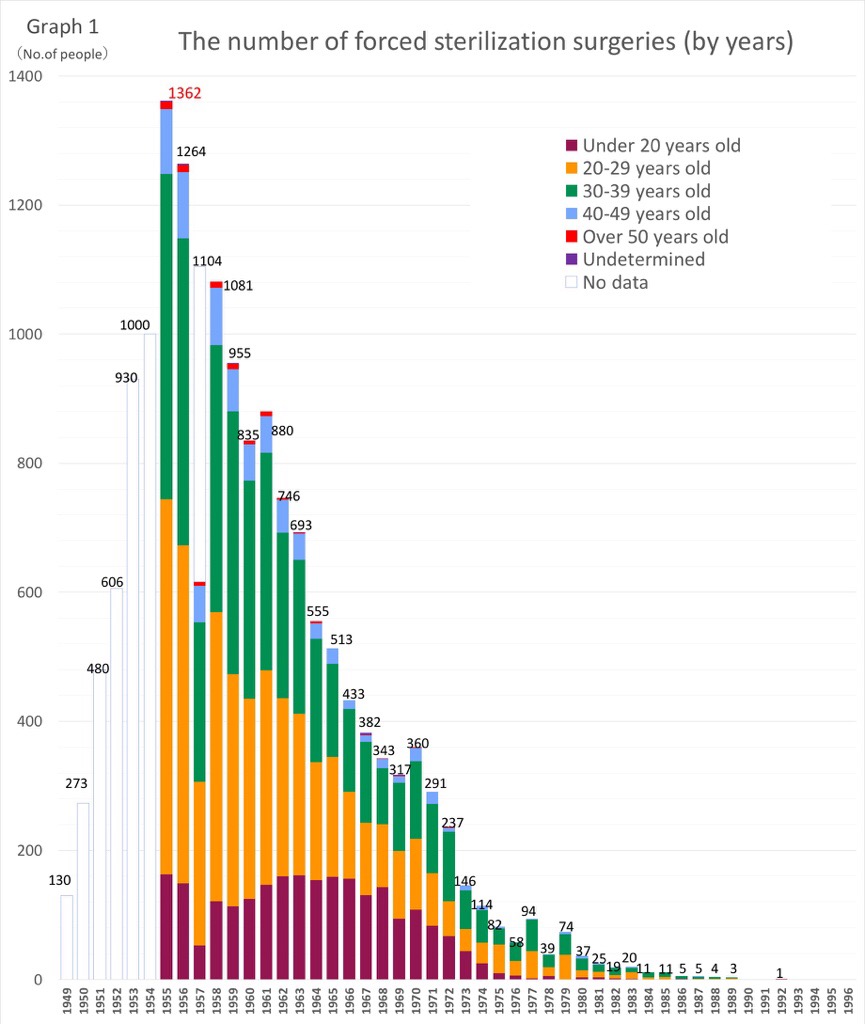

Number of forced sterilization surgeries by prefecture

Compiled from health ministry documents. Unable to retrieve data for 1952 and 1953.

Hokkaido officials boasted about number of surgeries

Hokkaido, Japan’s northern island, led the nation’s 47 prefectures with 2,593 surgeries. In a 1956 letter obtained by Tansa from the Kyoto Institute, Library, and Archives, Hokkaido government officials boasted to their Kyoto counterparts about the number of surgeries they had conducted.

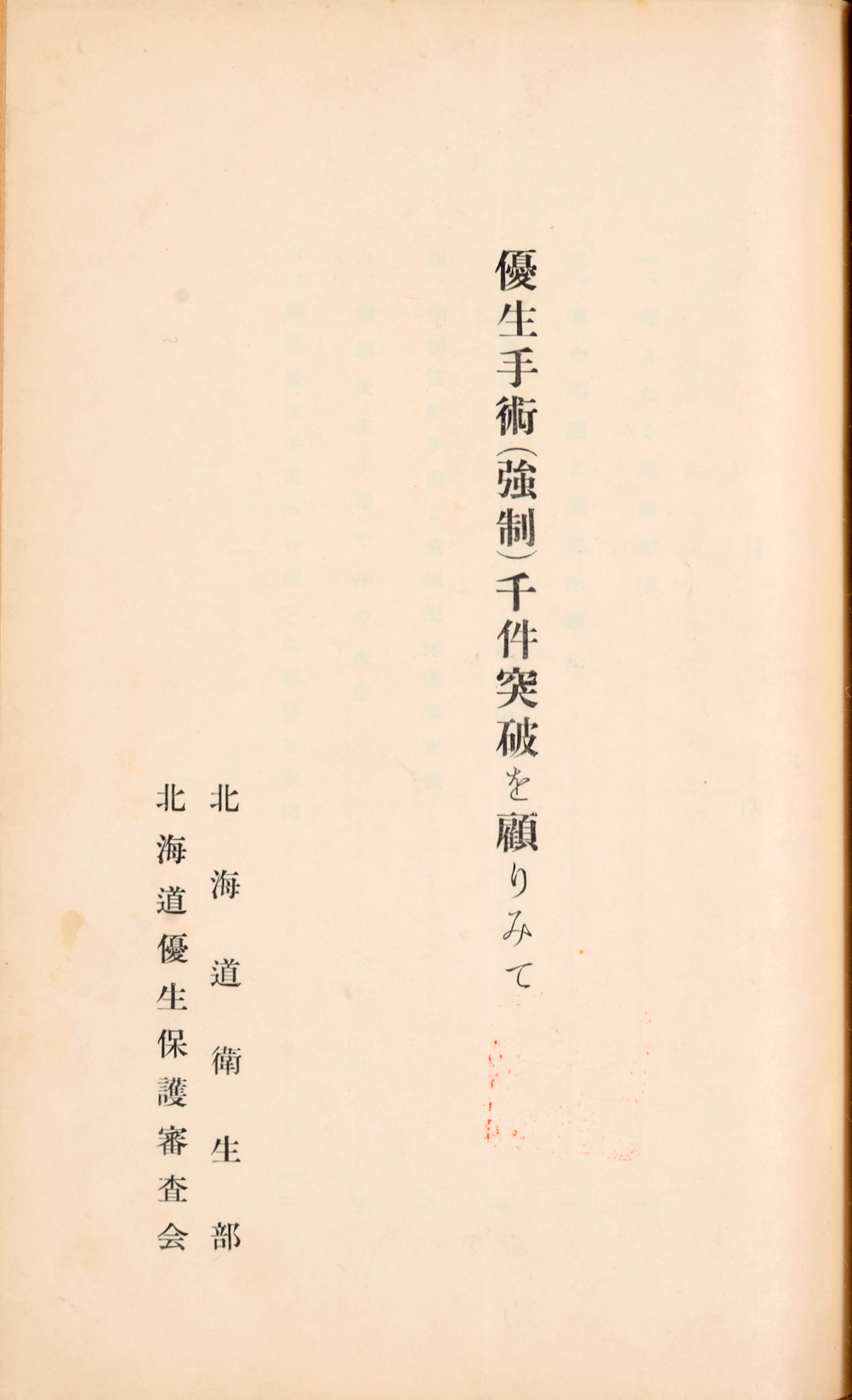

“The number of forced eugenic surgeries, with the help of doctors, review board members, and other affiliated officials, has increased year by year, with the number now surpassing 1,000 cases. We have printed documents that reflect this, attached as a reference,” said the letter. A 16-page commemorative pamphlet, produced by the Hokkaido government’s health bureau and the Hokkaido Eugenic Protection Review Board in 1956, bragged that surgeries conducted by Hokkaido account for “about one-fifth of the national total” and “greatly outnumber other prefectures.”

Commemorative pamphlet produced by the Hokkaido health bureau

“A great contribution to racial hygiene”

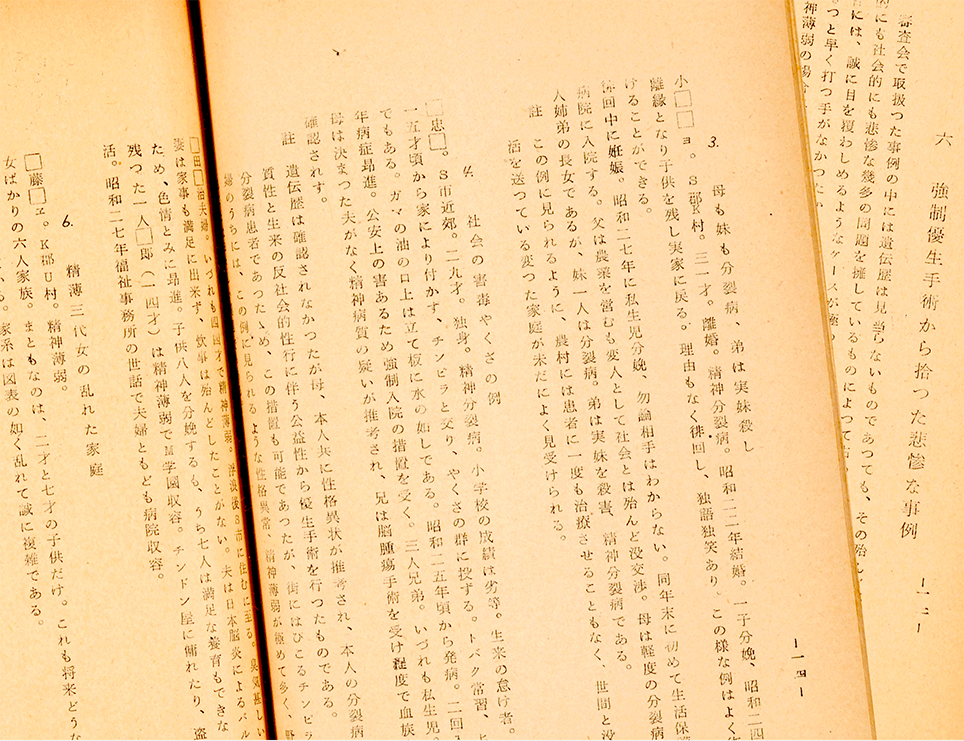

In the commemorative pamphlet, Hokkaido officials wrote that the high number of forced sterilization surgeries was greatly significant “from a racial hygiene perspective.” One section explained that the subjects of forced surgeries had “tragic” medical histories or family environments. The execution of forced sterilization surgeries was therefore a major responsibility, it said.

Below are excerpts from the 1956 commemorative pamphlet.

・ “A family of eight brothers, three with epilepsy”

“One has the intelligence of a first-grade elementary school child. An older brother has epilepsy and died at 21. Their younger brother is a laborer who has an epileptic fit about three times every two months. Father is a white-collar worker and lives an ordinary life, and the parents and the five sisters and brothers are normal, but an uncle on the mother’s side has epilepsy. A paternal uncle has schizophrenia and belongs to a typical epilepsy-heavy family.”

・ “A mother (42) who had three children even after showing symptoms of schizophrenia; one child is schizophrenic”

“Married, Schizophrenic. Had one child after marriage. Symptoms began at 29 years of age. Had three more children, and the second oldest daughter (13) was hospitalized for schizophrenia. The two others are still under 10 years old but are of concern. Eugenic surgery should’ve been conducted the first time she was released from the hospital.”

・ “Mother (31) and younger sister schizophrenic; younger brother killed own sister”

“Schizophrenic. Married 1947. Had one child, symptoms began in 1949. Divorced and left the child to return to parent’s home. Roams outside without reason, talks and laughs to herself; became pregnant by unknown father and bore an illegitimate child in 1952. Although her father is a farmer, he is considered odd and is socially isolated. Mother has mild schizophrenia. Younger brother, who killed his sister, suffers from schizophrenia.”

・ “A Yakuza gang member (29)”

“Single. Schizophrenic. Under-performer in elementary school; innately lazy. Has wanderlust and left his family at 15, mingled with thugs and joined a Yakuza group. A gambling and meth addict. Has three brothers, all born out of wedlock. Mother is unmarried and strongly suspected of being a psychopath. No hereditary evidence but strong suspicion of personality disorder in both him and his mother, so eugenic surgery was conducted, considering his schizophrenia and the preservation of public wellbeing from his anti-societal activities.”

・ “A disturbed family consisting of three generations of mentally disabled women”

“The only sane family members of the female subject who was sterilized are two children, aged two and seven, but their future is cloudy. They are on welfare. The subject’s mother is mentally disabled, and remarried after her husband ran away. The subject was born around this time and is also mentally disabled and sexually lewd. She has three daughters with her father-in-law. He is a fisherman but passed away a few years ago, and she allows a homeless man to live with her. She had an abortion five months into a pregnancy. Her younger daughter (17 years old, mentally disabled) also aborted a child whose father is unknown seven months into her pregnancy. Her older daughter (19 years old, mentally disabled) is extremely beautiful. She attracts attention from coal miners, and becomes sexually involved with them for small amounts of money. All three have been hospitalized.

“This situation could have been prevented had measures been taken with the grandmother. Either way, the problem is that this family was free for over 20 years. It’s hard not to shake one’s head in disappointment, knowing they receive social and medical welfare.”

The 1956 Hokkaido commemorative pamphlet

“The government is addressing this issue head-on”

The commemorative issue pointed out that 85% of subjects who underwent surgery were schizophrenics. Yet it lamented that 14,000 people in Hokkaido with mental disabilities and psychopathic disorders were yet to be treated. The Hokkaido government concluded that it was “hoping for more proactive cooperation” from relevant officials.

Hokkaido Prefecture’s actions were backed by a national agenda based on the Eugenic Protection Law.

“Improving the quality of our people is an ageless necessity,” read the pamphlet. “It’s especially important as we revive our national capabilities and hope for the realization of a bright civilized state. The government addressing this issue head-on a big step forward for ethnic hygiene.”

The health ministry (now the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare) aggressively pushed local governments to increase the number of forced sterilization surgeries.

A letter sent on April 27, 1957 to local government officials from Dr. Rokuro Ohashi, a mental health department manager at the health ministry’s public health bureau (*10), included the following.

“The number of eugenic surgeries conducted is increasing year by year but has yet to reach the target.

“The number of surgeries between prefectures, as seen in the attached document, are extremely uneven. This isn’t because there aren’t potential subjects, but because there is room for growth depending on the level of advocacy activities and efforts made by relevant officials.

“Please give the utmost care and effort to the eugenic surgeries to be conducted this year.”

Local government officials across Japan were fully aware of the health ministry’s intentions, and some were even conscious of the number of surgeries conducted in other prefectures.

Kyoto Prefecture: 10% of mental hospital patients are potential subjects

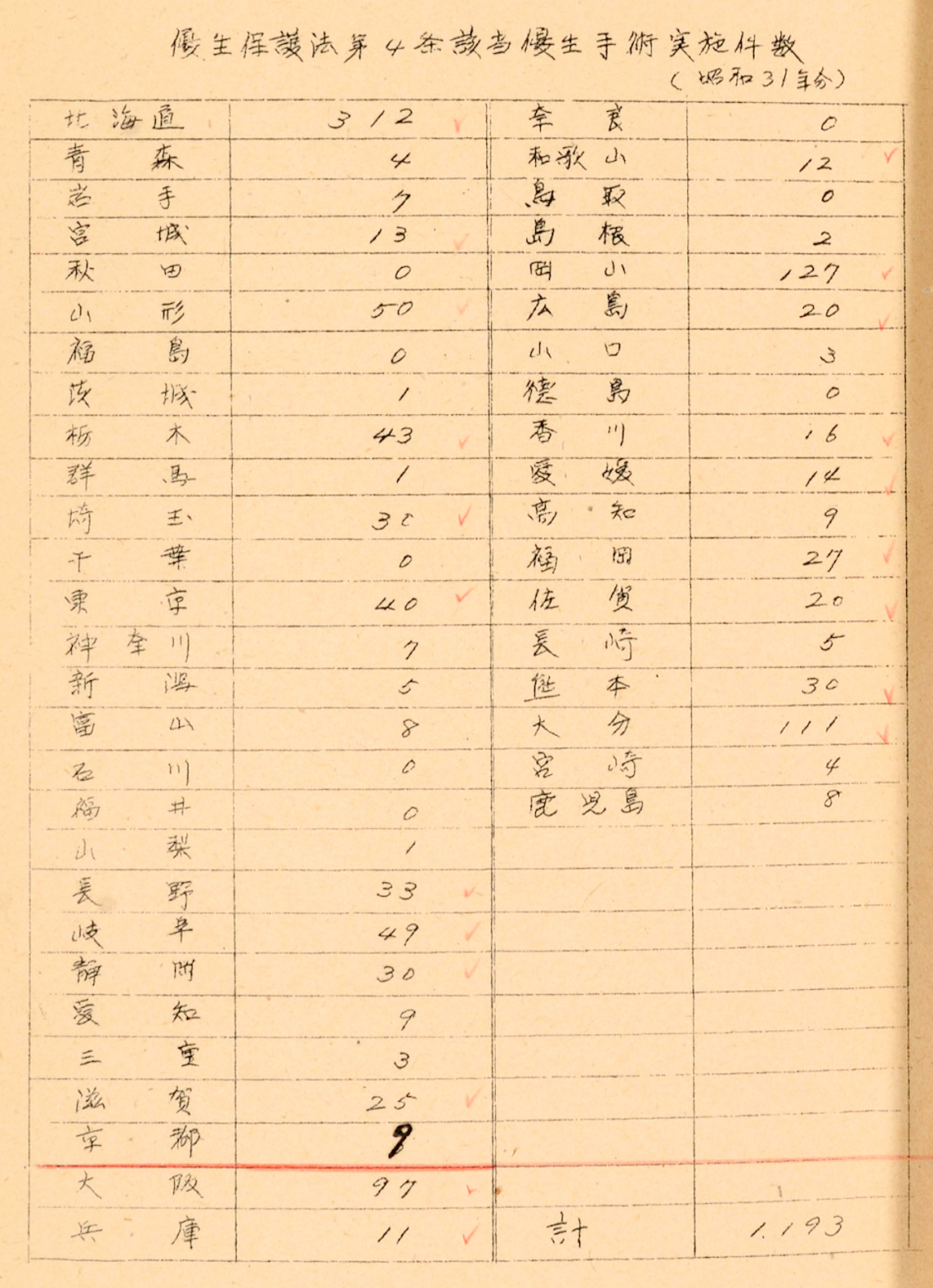

Ohashi’s letter included a chart detailing the number of surgeries conducted by prefecture. A red check was drawn next to every prefecture with numbers higher than Kyoto Prefecture.

Chart detailing the number of surgeries conducted by prefecture, from Rokuro Ohashi's letter

There were signs that Kyoto Prefecture had tried to raise the number of surgeries even before the health ministry’s request.

On Jan. 25, 1955, a manager at Kyoto Prefecture’s public health bureau sent a document titled “On conducting eugenic surgeries on the mentally ill at all local hospitals.”

In the document, the manager decried the low application numbers of potential subjects to the local eugenic protection review board and noted other prefectures with higher numbers.

“It is a serious concern that the application numbers are extremely low [in Kyoto] while the number of the mentally ill is increasing annually,” the document read.

“As a reference, over 200 eugenic surgeries are conducted in Osaka hospitals, and there are significant numbers of surgeries conducted in Hyogo Prefecture, so we estimate that about 10% of patients at mental institutions are potential subjects for eugenic surgery.”

Forced sterilization extended to disabled children

Just two months after the above letter from Kyoto Prefecture’s public health bureau, calling for more involvement by mental institutions, was sent, a document titled “On conducting eugenic surgeries on the mentally disabled” was dispatched by the same bureau to the heads of institutions for disabled children. The document, dated March 7, 1955, asked for the institutions’ cooperation in finding mentally disabled children as potential subjects for sterilization surgery.

“Among the children institutionalized for mental disabilities, we believe there are those who fall into the category of having hereditary mental disorders,” the document read. “We strongly request that you consider the eugenic surgery guideline.

“In addition, the cost of each surgery will be covered by the prefectural budget.”

“Numbers low compared to other prefectures”

On July 22, 1964, the Hiroshima Prefecture health director asked local mayors and public health centers to seek potential subjects for sterilization surgery.

“Despite eugenic surgeries being handled by Hiroshima’s eugenic protection review board, the numbers are low compared to other prefectures, and we believe there is a lack of information dissemination about the program,” read the letter, titled “On Eugenic surgery applications based on the Eugenic Protection Law.” We obtained the letter through a freedom of information request to the Hiroshima prefectural government.

At a eugenic protection review board meeting held on June 17, 1977, in Mie prefecture, a member of the board expressed concern about the lack of applications in 1975 and 1976.

“Perhaps it’s a matter of instruction. The numbers are high in northeastern Japan,” said the board member, an assistant judge of a local court in Tsu City, according to meeting minutes.

These statements illustrate how local governments were conscious of one another’s performance, and equally conscious of the national agenda based on the Eugenic Protection Law.

Victims include more than 2,300 minors, some as young as nine

Statistics produced by the health ministry and other reports illustrate the scale of the national project.

Over the 50 years until the law was amended, 16,518 people were forced to go through sterilization surgeries. About 90% were carried out in the 1950s and 60s. In 1955, three years after the law was amended to include people with non-hereditary mental disabilities, the number peaked at 1,362 in a single year. Although the exact gender divide is unclear due to insufficient historical data, the health ministry’s numbers show that more than twice as many women were sterilized as men.

In two cases, in 1963 and 1974, nine-year-old girls were sterilized, according to surgery records kept by Miyagi Prefecture. Among the 2,390 victims under 20 years old, 70% were female. In Kyoto Prefecture, a 12-year-old girl was forcibly sterilized for “epilepsy and idiocy,” according to a document obtained by Tansa.

The greatest number of victims — 4,673 — were in their 20s. The most recently recorded surgery was conducted on a woman from Fukuoka Prefecture who was under 20 years old. She would now probably be in her 40s.

Forced sterilization surgeries were conducted in all Japanese prefectures. Hokkaido had the highest number at 2,593, followed by 1,406 in Miyagi, and 845 in Okayama prefecture.

Many of the younger victims are now in their 50s and 60s.

The data was produced by adding the number of surgeries conducted under Article 4 (involuntary sterilization of people with hereditary disorders or disabilities) and Article 12 (involuntary sterilization of people with non-hereditary disorders or disabilities) of the Eugenic Protection Law, both compiled from health ministry documents. Source documents: 1949 – 1952, 1954 – 1959 taken from the health ministry's Annual Health Report. 1953 taken from the healthy ministry's 1975 Eugenic Protection Law Designated Doctors Workshop Document. 1960 – 1995 taken from Eugenic Protection Statistical Report and 1996 taken from Maternal Protection Statistical Report, both from the health ministry. There is no data on 1948 when the law was enacted. Data separated by age produced by Tansa. Numbers are not listed on documents for 1949 – 1954. Data for 1957 may be wrong, according to the health ministry.

Involvement of public prosecutors and judges

According to the Eugenic Protection Law, doctors were responsible for reporting potential subjects of sterilization surgeries to the prefectural review board, which then would make the final call on whether to conduct the surgery. Review boards included heads of medical associations, deputy prosecutors, and domestic court judges. They were appointed by prefectural governors, according to documents obtained through freedom of information requests sent to 47 prefectural governments.

However, as it was in Hokkaido, Kyoto, Hiroshima, and Mie, the local governments played a central role in finding potential subjects and increasing the number of surgeries.

Newsletter signup

Newsletter signup