Drug Pricing Organization chairman hands off responsibility to health ministry (2)

2020.10.06 18:14 Makoto Watanabe

5 min read

Among the Drug Pricing Organization’s (DPO) 11 core committee members, three — including the chairman, University of Tokyo professor of geriatric medicine Masahiro Akishita — each received over 10 million yen (about $94,000) in additional income from pharmaceutical companies in fiscal year 2016. Tansa learned of the payments made to committee members through our Money for Docs database, created in partnership with the Medical Governance Research Institute.

The DPO is a subsidiary organization of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare’s Central Social Insurance Medical Council, the latter of which approves the DPO’s pricing plans for new prescription drugs.

The health ministry does not disclose information about the income DPO members receive from pharmaceutical companies. Committee members are barred from voting and participating in deliberations if their additional income from pharmaceutical companies crosses certain thresholds. But without disclosure, it is difficult to verify whether the DPO is abiding by these regulations.

On May 13, 2018, Tansa interviewed DPO committee chairman Akiyama following a lecture he gave at the Toshi Center Hotel in Tokyo.

DPO committee chairman Masahiro Akishita speaks at an event at the Toshi Center Hotel in Tokyo. Photo by Tansa.

Playing by the rules?

According to our Money for Docs database, Akishita received a total of 11.6 million yen (about $109,000) from pharmaceutical companies in lecture, article writing and supervision, and consulting fees in fiscal year 2016.

The majority of his earnings came from three companies: Daiichi Sankyo at 5.6 million yen (about $53,000), Takeda Pharmaceutical Company at 2.4 million yen (about $23,000), and MSD at 1 million yen (about $9,500).

DPO regulations state that if a committee member has received over 500,000 yen (about $4,700) in a single fiscal year from a company whose drug the committee is evaluating, they forfeit their voting right for that drug. For amounts over 5 million yen (about $47,000), they cannot even participate in deliberations. Committee members are required to declare payments they receive from pharmaceutical companies whose drugs they are evaluating.

According to these regulations, Akishita would not have been able to participate in deliberations on drugs manufactured or sold by Daiichi Sankyo. And he would not have been able to vote on drugs by Takeda Pharmaceutical or MSD.

The prices of 208 new drugs were set from April 13, 2016 to May 16, 2018. They included 14 manufactured or sold by Daiichi Sankyo, seven by Takeda Pharmaceutical, and 13 by MSD.

As such, the DPO chairman would have been barred from voting and/or deliberations on roughly 15% of the new drugs whose prices were set during this period. Were the rules being upheld?

“I was absent a fair bit”

“My memory isn’t perfect — the secretaries handle everything, you see,” Akishita began when we asked about his attendance record. “They’re the ones who calculate it all. Then the health ministry people check it.”

“I was absent a fair bit,” he continued. “No participation in the discussions, nothing.”

Payments from Daiichi Sankyo, Takeda Pharmaceutical, and MSD accounted for 9 million yen (about $85,000) of Akishita’s total 11.6 million yen received from pharmaceutical companies in fiscal year 2016. Just three companies had contributed roughly 80% of his earnings. Was there a reason for their consistent patronage?

“I’m involved in primary care,” Akishita explained when we asked. “It’s a combination of blood pressure, diabetes, that sort of thing. That’s why the majority of my pharma income comes from companies whose products treat a variety of conditions.”

“The DPO doesn’t have as much power as you think”

Akishita insisted that he had never tried to raise the price of a drug to benefit a pharmaceutical company.

“Drug prices aren’t just left to the committee members’ discretion,” he explained. “There are super strict rules — not set by us — [on calculating the prices]. The gist of our discussions is basically ‘Maybe this drug could be a little higher,’ ‘Don’t you think this one is too expensive?’ ‘But that’s what the rules say, so there’s no helping it.’

“I can’t think of a single instance where we’ve deliberately raised [the price of a drug].”

Akishita also told us that the DPO committee’s deliberations were led by the health ministry, which manages the organization.

“Questions are answered by [a ministry] expert officer. Or sometimes the Medical Economics Division head. I never speak on these matters, since there’d be trouble if I turned out to be wrong. I just listen to the experts and then clarify a few points later. That’s what the committee does. The DPO certainly doesn’t have as much power as you think.”

But the picture Akishita painted didn’t match our understanding of the DPO’s role and work process.

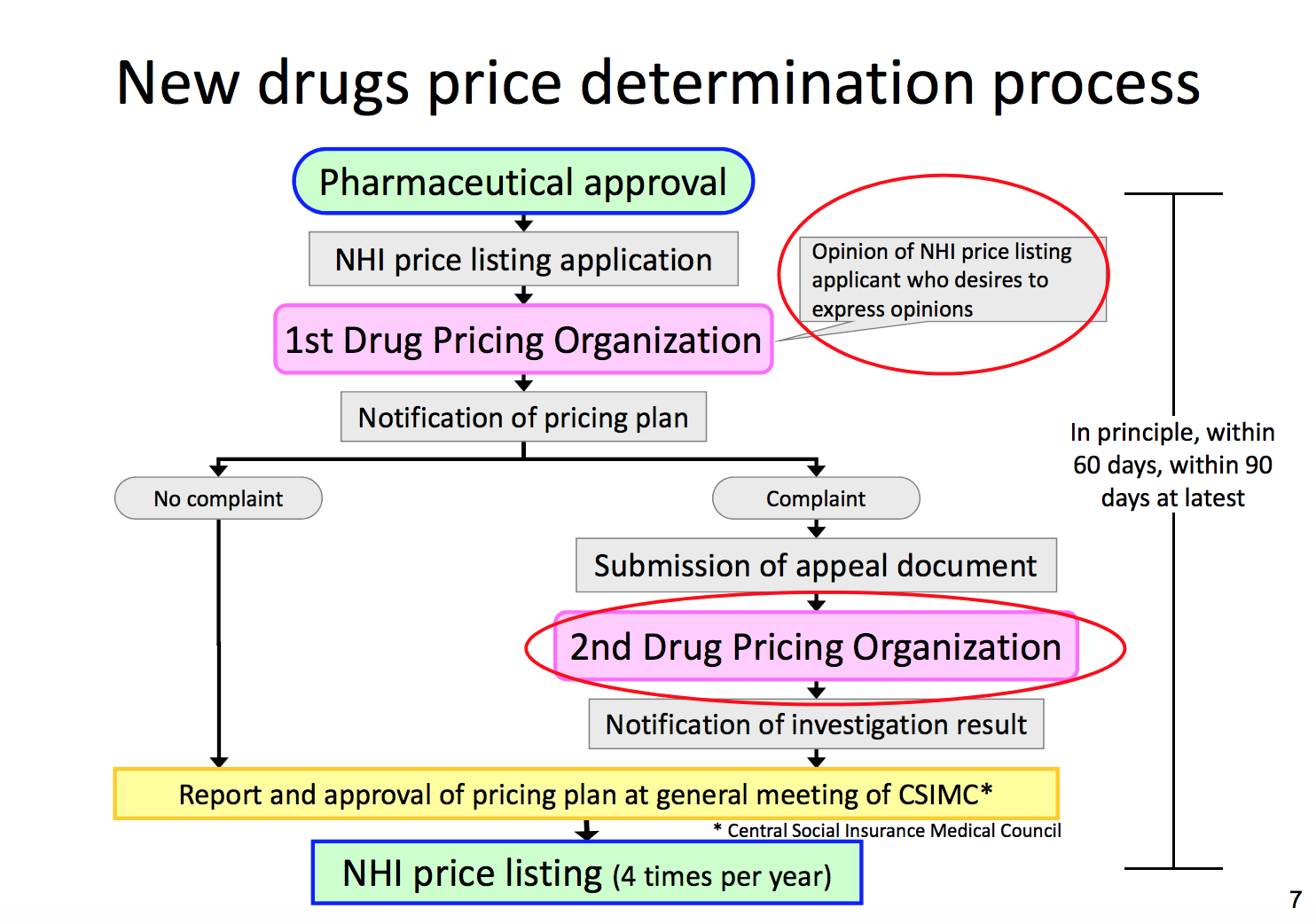

To review, this is how prescription drug prices are set. Following a new drug’s approval for manufacture and sale, the DPO calculates a pricing plan on behalf of its parent organization, the Central Social Insurance Medical Council. The DPO chair makes quarterly reports to the council’s general meeting, at which the pricing plans are approved.

The Drug Pricing Organization develops pricing plans, which are then approved by the Central Social Insurance Medical Council. Chart by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. (Red circles in original.)

Looking at this structure and process, it would be natural to assume that the DPO has a certain level of influence over drug prices.

But Akishita, the organization’s head, denied that influence, saying it was even annoying how little sway the DPO had. He placed responsibility squarely with the health ministry.

So did that mean the ministry was taking a leading role in determining the price of drugs?

Committee chairman chosen for his CV

Akishita had said that he wasn’t a particularly active participant in the committee’s deliberations and that health ministry officials were the ones to answer questions. If that was the case, why had Akishita been selected as DPO chairman?

“Well, I have a certain amount of name value,” he said when we asked. “I’m a professor at the University of Tokyo [Japan’s top university], and my work relates to [overall healthcare for the elderly]. I mean, at the very least, I’m not unsuited for the position.”

Toward the end of our interview, we asked what Akishita, in his capacity as DPO chairman, thought of the health ministry not disclosing the DPO members’ conflicts of interest with pharmaceutical companies. And what did he think of doctors receiving substantial payments from big pharma in the first place?

The chairman’s reply was not what we expected.

… To be continued.

(Originally published in Japanese on June 22, 2018. Translation by Annelise Giseburt.)

Money for Docs: All articles

Newsletter signup

Newsletter signup