Drug Pricing Organization chairman advocates doctors’ “voluntary restraint” from pharma-sponsored events (3)

2020.10.20 18:22 Makoto Watanabe

5 min read

In Japan, drug prices are set by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare’s Central Social Insurance Medical Council, which makes its decisions based on pricing plans developed by the Drug Pricing Organization (DPO). But these prices are determined within a black box: The ministry discloses neither DPO members’ names nor the money they earn in additional income from pharmaceutical companies. Even our freedom of information request for the latter was denied. (See this series’ second article for details.)

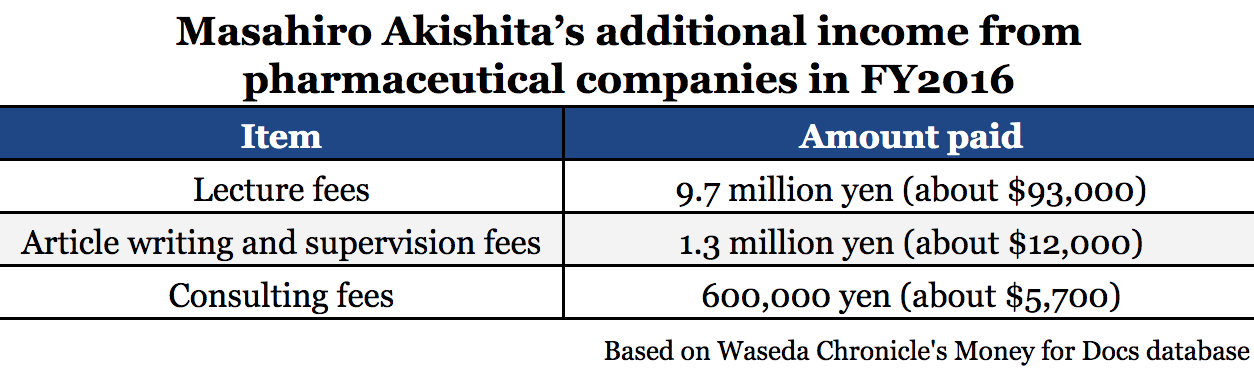

Three members of the DPO’s core committee — including University of Tokyo professor of geriatric medicine Masahiro Akishita — each received over 10 million yen (about $94,000) in additional income from pharmaceutical companies in fiscal year 2016.

Tansa interviewed Akishita on May 13, 2018; this series’ previous article covers his comments on the DPO’s operations. We also asked what Akishita thought about doctors and DPO members, himself included, receiving significant additional income from pharmaceutical companies. Here’s what he had to say.

Invited to speak at pharma-sponsored events by other doctors

Akishita is both a practicing physician and head of the organization responsible for calculating prescription drug prices in Japan. And he received a total of 11.6 million yen (about $109,000) in additional income from pharmaceutical companies in fiscal year 2016, according to our Money for Docs database.

The vast majority of Akishita’s pharma income was in lecture fees, but he denied promoting specific products in his talks.

“I know it sounds like an excuse, but I get roped into doing these lectures by professional acquaintances — by other doctors,” he told us. “And then it turns out the lectures are sponsored. That happens quite a bit, actually: I accept a lecture request then get contacted by pharma people. You can understand it puts me in an awkward position.”

More lecture invites since becoming a professor

We asked Akishita whether he felt uncomfortable speaking at pharma-sponsored events.

“I started getting invited to more of these lecture events since becoming a professor,” he replied. “And it is important to attend lectures as part of my academic activities. But then it’s like, ‘Is it really ok to be attending pharma-sponsored lectures?’ Those held by medical associations would be ok, but it’s like, ‘Why pharma?’ you know? Personally, I have reservations about it.

“These days, I turn down just about nine out of 10 lecture requests I receive. I hold myself to a certain standard to do as few of these events as possible.”

Akishita went on to say that many of his colleagues at the University of Tokyo Hospital observe this kind of voluntary restraint. He cited a 2014 scandal in which University of Tokyo Hospital doctors shared drug trial patient data with the pharmaceutical company Novartis as the reason his colleagues now keep big pharma at a distance.

“[The Novartis incident] really changed how things were done. But I think we’re heading in that direction anyway, overall,” Akishita said.

“Don’t write anything negative”

We asked whether Akishita thought doctors’ additional income from pharmaceutical companies should be disclosed to the public.

“Well, I wouldn’t really want just anybody to be able to see it,” he began.

“For example, I wouldn’t like it if my neighbors gossiped about me. My wife would stress about how to recycle invoices — what if someone saw? I don’t think any doctor would want to be an object of attention like that.”

We reminded Akishita that we weren’t asking what he thought about doctors’ total earnings being disclosed, just income from pharmaceutical companies — a measure to ensure that doctors don’t prioritize the drugs sold by their benefactors.

“I know,” Akishita replied. “And I know that that sort of system is necessary.”

In fact, in some parts of the world, such transparency measures are already taking shape. For example, the U.S.’s Physician Payments Sunshine Act requires pharmaceutical companies to report payments of $10 and above, including the recipient doctors’ names. Data collection began in 2013, and a national database went live the next year. The issue of conflict of interest in medicine received significant attention in the U.S. following the death of 18-year-old Jesse Gelsinger in a clinical trial in 1999 — one of the researchers had failed to disclose that he stood to benefit from the trial’s results.

Doctors in Japan feel a similar urgency. A Science Council of Japan committee on clinical trials has called for the creation of a database compiling information on payments to doctors, as well as payments to medical facilities and organizations. Such measures are vital for increasing transparency and maintaining ethical conduct.

During our interview, Akishita asked us not to write anything “weird” or “negative,” as well as requested to meet again before we released any articles.

The latter was fine with us: We asked for a second interview. But in the end, Akishita turned us down, citing his busy schedule. On May 22, 2018, Akishita sent us the following written response via the University of Tokyo Hospital public relations office.

With regard to the DPO committee members’ current nondisclosure of their additional income from pharmaceutical companies, Akishita wrote: “I believe disclosure is an issue that deserves further consideration, in coordination with the relevant ministries and organizations and taking into account the social landscape going forward.”

A true representative of his profession, Akishita made no promises.

(Originally published in Japanese on June 29, 2018. Translation by Annelise Giseburt.)

Money for Docs: All articles

Newsletter signup

Newsletter signup