Japan vocal on leaked nuclear tech — when it’s another country’s problem

2020.08.25 19:45 Makoto Watanabe

5 min read

Tatsuya Takemura, a nuclear scientist who worked for the former Power Reactor and Nuclear Fuel Development Corp (PNC), was born in 1935. If he’s still alive, he’ll be 85 this year. Those investigating his disappearance, whether police or journalist, have no time to waste.

So what leads hadn’t we examined yet?

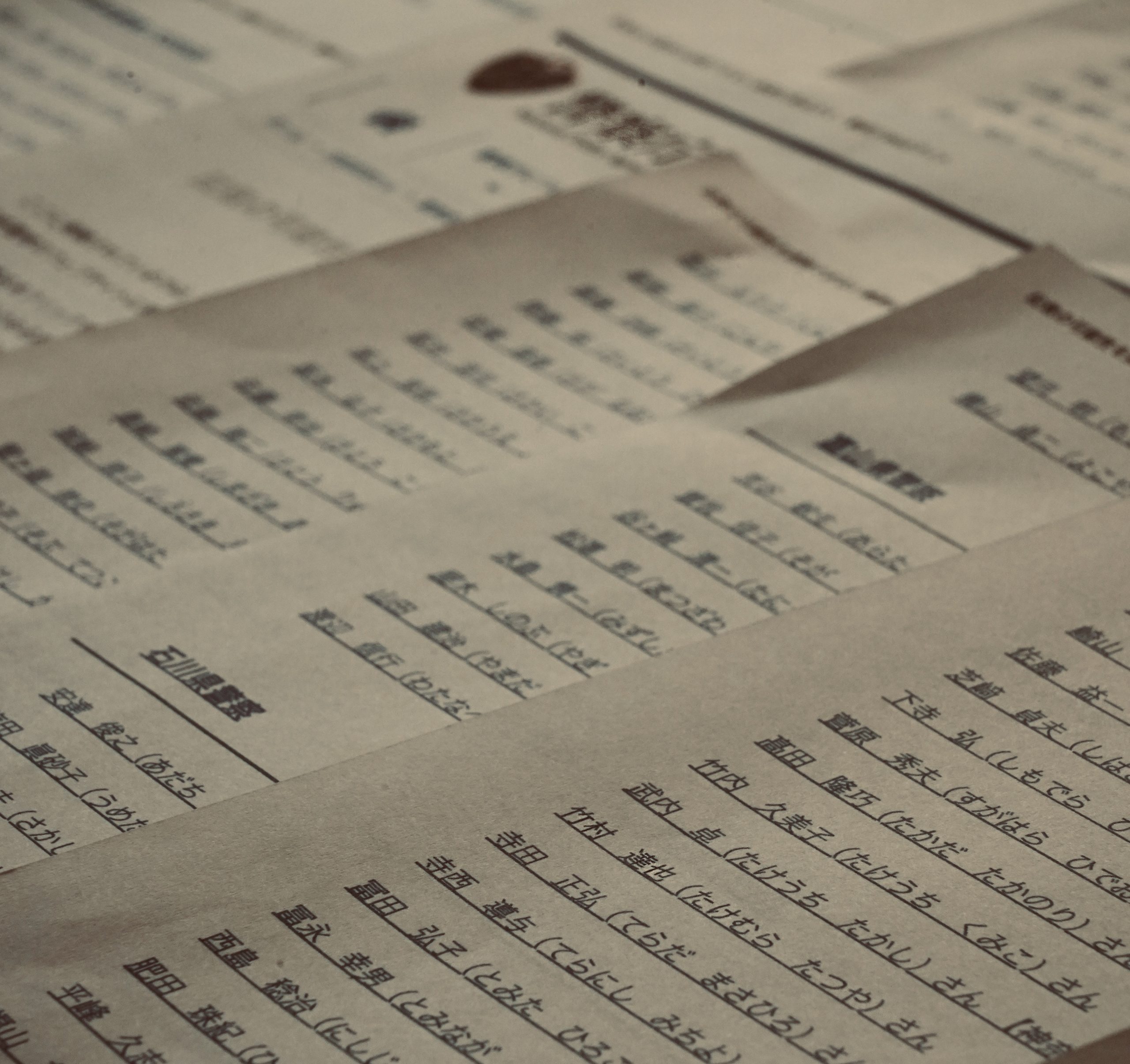

The police’s list of “cases in which the possibility of abduction cannot be ruled out” (C)Tansa

Robotic control and precision machine specialists also missing

Maybe other specialists possessing skills coveted by North Korea had disappeared too.

A Tansa member scoured the National Police Agency’s online list of “Cases in which the possibility of abduction cannot be ruled out.”

We compared each entry with past newspaper articles and information published by the Investigation Commission on Missing Japanese Probably Related to North Korea, a private citizens’ group.

Sure enough, the potential abductee list contained other experts in addition to Takemura.

Fifty-six were university or graduate students in specialized fields. Eleven, including Takemura, were public servants. And five were retired officials from Japan’s Self-Defense Forces.

Among these, we found two cases of particular interest.

The first was Koichi Kawashima, who had disappeared from Yokohama’s Kanazawa Ward. According to the police’s list, he was 23 years old and unemployed at the time of his disappearance.

“Kawashima’s parents had driven to Yokohama to help him move home to Hamamatsu following his graduation from university,” the list noted. “Although they had planned to drive back together on March 21, 1982, Kawashima suddenly decided to take the train instead. His whereabouts have been unknown since.”

Newspapers covered the case in more detail. The Chunichi Shimbun, which has a regional headquarters in Hamamatsu, reported the following in 2014.

“Kawashima had conducted research in robotic control at Kanto Gakuin University’s College of Engineering. He went missing in March 1982, after graduating and moving out of his accommodation in Kanazawa Ward, Yokohama.”

In other words, although the police had simply listed him as “unemployed,” in fact Kawashima had been studying robotic control, a field with various applications in military technology.

The second case was Tomiyasu Yakura in Tottori Prefecture. The police’s list gave his occupation as “fishing industry,” and it merely noted that Yakura had gone missing after departing the port city of Sakaiminato in his fishing boat, which was later discovered near the Liancourt Rocks in the Sea of Japan.

Yet according to the Investigation Commission on Missing Japanese, until three years before his disappearance, Yakura had worked at Japan’s leading manufacturer of precision machine tools. He had even been sent abroad to provide technical guidance. But the company went under, and Yakura became a fisherman.

His parents, stressing that they believe their son to have been abducted by North Korean agents, lodged a criminal complaint with Yonago Police Station against the as-yet-unknown culprits in 2007.

A number of suspected abductees were highly skilled individuals who could contribute to North Korea’s military technology. The Japanese government and police knew it, but it seems they didn’t want anyone else to.

Skills applicable to nuclear weapons development

Takemura had been head of plutonium production at PNC. Could his knowledge and skills be applied to nuclear weapons development?

I met with two scientists who had been Takemura’s subordinates in PNC’s plutonium fuel department.

“Takemura worked on the oxidation of plutonium, to make it into nuclear fuel,” the first said. “That by itself isn’t enough to produce nuclear weapons. I’d say it would take at least 20 years for North Korea to actually do so, even if Takemura were involved.”

He continued: “Plutonium is really difficult work with. Its crystal structure and density change depending on its temperature. If Takemura was, in fact, abducted and forced help manufacture nuclear weapons, I imagine he’d be helping them handle plutonium.”

The second scientist also thought Takemura’s skill set could be put to use.

“Plutonium is an essential part of nuclear weapons development, but [its extreme radioactivity means that] inhaling even a little is enough to give you lung cancer,” he said. “You need to know how to work with it through a glovebox, a sealed container that prevents exposure. North Korea probably was in need of someone with those skills.”

He called Takemura a member of the “first generation” of Japanese scientists to study nuclear technology at an American facility.

“If someone from the first generation were involved in North Korea’s nuclear weapons development, he probably would have played a pretty significant role.”

According to the two scientists, Takemura most likely could have been useful to North Korea’s nuclear weapons program. And yet, the police and the Japan Atomic Energy Agency (formerly PNC) were not even doing the bare minimum to pursue his case.

“The tip of the iceberg”

Although Takemura’s involvement remains in the realm of speculation, another nuclear scientist confessed to having assisted North Korea’s quest for nuclear weapons.

In February 2004, Pakistani nuclear physicist Abdul Qadeer Khan admitted on national television to having passed nuclear technology to Libya, Iran, and North Korea.

The revelation of a nuclear black market shook the world, Japan included.

The day after Khan’s confession, International Atomic Energy Agency Director General Mohamed ElBaradei called the scientist’s actions merely “the tip of the iceberg” and emphasized the nuclear black market’s sophisticated network.

Ten months later, in December 2004, the Japanese Diet’s upper house established the Special Committee on the North Korean Abduction Issue and Related Matters.

“North Korea confirmed the existence of its uranium enrichment program to a visiting U.S. delegation in October 2002,” said Minister of Foreign Affairs Nobutaka Machimura at the time. “Japan too is gathering relevant information, including that which is related to Dr. Khan’s statements.”

Furthermore, Vice-Minister for Foreign Affairs Shintaro Ito said the following at a lower house Diet session in June 2009.

“It has come to light that Dr. Khan visited [North Korea] multiple times and was involved in exporting nuclear technology from Pakistan.

“Japan finds it extremely regrettable that various forms of nuclear technology leaked to North Korea and other countries, thereby harming international peace and stability, as well as nuclear nonproliferation systems.”

The two politicians’ comments reflect Japan’s commitment to aiding the U.S. and other nations to stop the flow of nuclear technologies into North Korea.

But had Japan informed its allies of its own potential leak?

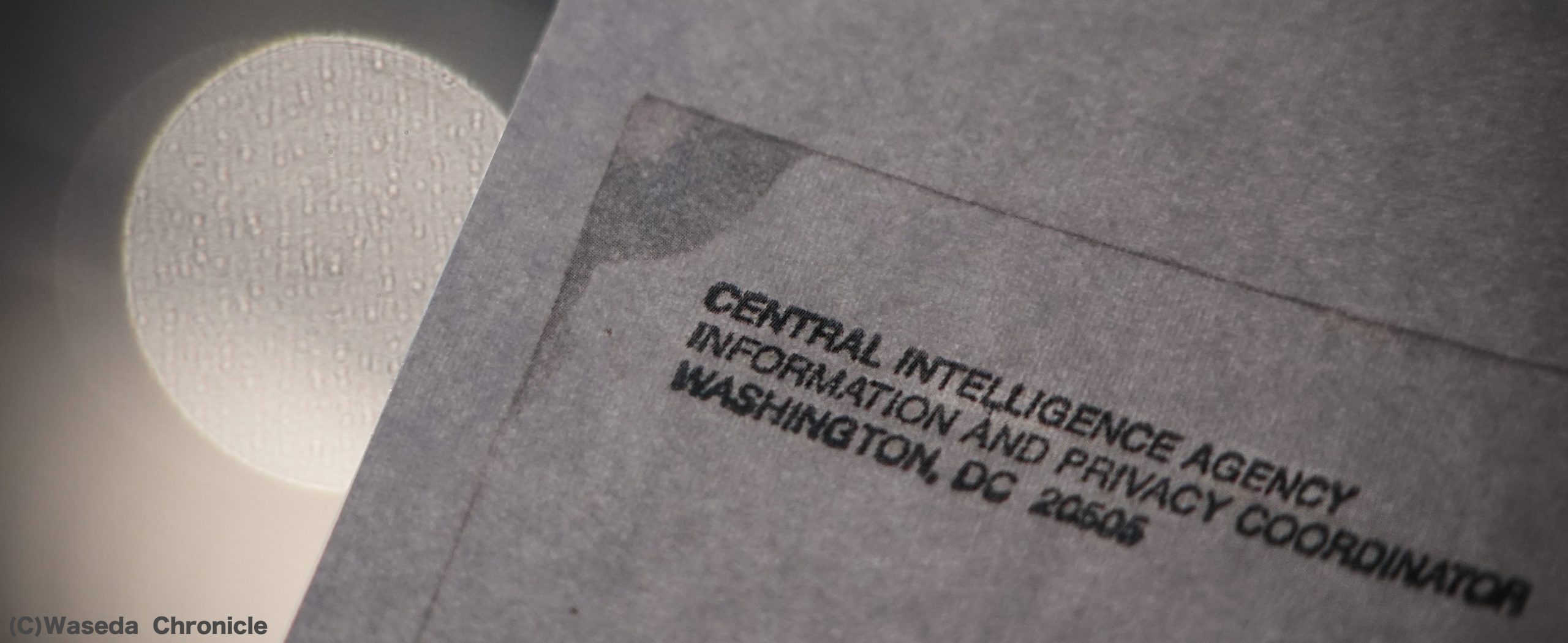

Tansa sent a freedom of information request to the U.S.’s Central Intelligence Agency, to see whether it has any information on Takemura’s disappearance. So far, the CIA has found none among its records.

The CIA’s response to Tansa. It has not yet found any information related to Tatsuya Takemura. (C)Tansa

… To be continued.

(Originally published in Japanese on May 22 and June 2, 2020. Translation by Annelise Giseburt.)

———

What was North Korea’s objective in abducting Japanese citizens? Is Japan fit to handle nuclear technologies? With these questions in mind, Tansa is pursuing an independent investigation into the disappearance of former Power Reactor and Nuclear Fuel Development Corp scientist Tatsuya Takemura. This series is produced in collaboration with tabloid Nikkan Gendai, in which it is also published.

Get in touch with Tansa if you have information about the disappearance of Tatsuya Takemura. Please refer to our whistleblower support page for information on secure contact methods.

The Missing Nuclear Scientist: All articles

Newsletter signup

Newsletter signup