Nuclear agency and police dropped the case

2020.07.03 18:02 Makoto Watanabe

8 min read

In the early 1970s, the former Power Reactor and Nuclear Fuel Development Corp (PNC) and the Ibaraki Prefectural Police’s Katsuta Station (now Hitachinaka Station) worked closely to “protect PNC’s nuclear materials from extremist groups.” Their main surveillance target was the PNC labor union.

Soon after nuclear scientist Tatsuya Takemura disappeared, a detective from Katsuta Station speculated that “he might have been carried off by the North.” If abduction was a possibility, it would be natural for PNC and Katsuta Station to have pursued the case.

“I really should have heard about it”

I looked for someone who had belonged to PNC’s general affairs department, which had been the focal point for the organization’s collaboration with the police.

Once again turning to my trusty employee directory, I found a man who had been general affairs manager of both PNC’s Tokai office and its Tokyo headquarters, in addition to serving as secretary to the chairman of PNC’s board of directors. Although 10 years younger than Takemura, he had similarly been among PNC’s elite.

And, like Takemura, he had experience with the U.S., having participated in negotiations for Japan to receive permission to reprocess spent nuclear fuel (which happens to produce weapons-grade plutonium). I called on the man at his home, hoping that, given his career, he had looked into Takemura’s disappearance. But I was out of luck.

“Can’t say I know him,” he said when I showed him Takemura’s photo. “I don’t recognize his face.”

After serving me a glass of cold barley tea, he took another long look at the photo.

“Although Takemura is only reported as missing, there’s a possibility that he was abducted by North Korea,” I explained.

“The disappearance, much less the potential abduction, of a plutonium expert is a serious matter,” the man said. “It should have been treated as such. But there was no follow-up, and I never heard anything about it.

“I was head of general affairs at PNC’s Tokai office and later secretary to the chairman. Although I was just an assistant, I was also part of the negotiations with the U.S. about fuel reprocessing and permission to possess [weapons grade] plutonium. If a serious incident like this occurred, I really should have heard about it. It’s so strange…”

He tilted his head, momentarily lost in thought.

“Is it true that PNC’s general affairs department worked with the Katsuta Station police to monitor the union?” I asked.

“Yes, we were often in contact. We also had meetings with the Ibaraki Prefectural Police headquarters once or twice per year. But I never heard anything about Takemura, really.”

Despite PNC’s professed efforts to protect its nuclear materials from “extremist groups,” it seemed the disappearance of one of its top scientists had been quickly forgotten.

“It would be the same at any company”

In 2005, PNC was restructured into the Japan Atomic Energy Agency (JAEA). I spoke on the phone with a representative from its PR department’s media section. When I explained Takemura’s disappearance and the possibility of abduction by North Korea, the line was silent for a full three seconds.

“Oh, I see,” they finally responded.

It seemed the employee wasn’t familiar with Takemura’s case. They agreed to speak in person, and I sent a list of questions about Takemura’s time at PNC and the organization’s response following his disappearance.

JAEA’s PR department is located on the 19th floor of its Tokyo office. When I arrived, the employee I had spoken to on the phone was accompanied by the department’s deputy manager, and it was the latter who mainly responded to my questions. But all they told me were the dates Takemura joined and left PNC, as well as his final position in the engineering department.

“As a national research organization, PNC was an independent administrative agency, and therefore we are required by law protect the personal information of its employees,” the deputy manager said. “We aren’t at liberty to discuss details without the consent of the individual in question.”

Takemura was missing. Of course there was no way to obtain his consent.

“Takemura’s case is part of the police’s open investigation into potential abductees,” I said. “Doesn’t the JAEA have a record related to his disappearance?”

“He disappeared after leaving PNC, so no, we don’t. Our records only cover the time he worked for us. It would be the same at any company: The record ends when the employee leaves the organization. That’s part of protecting personal information too, after all.”

But Takemura was a nuclear scientist. His whereabouts were a matter of national security. If such a person went missing, shouldn’t PNC report it to the government and the International Atomic Energy Agency?

When I said as much, the deputy manager replied: “These days, our nuclear technologies would be considered confidential information, so there would be a penalty for not following regulations. However, we don’t know how it was handled back then.

“I was just a kid in 1972 [when Takemura disappeared], and this one here wasn’t even born. That stuff about the general affairs department and police taking countermeasures against the union… We sure are lucky to work in an era of peace.”

I told them the words of a former PNC scientist I had interviewed: “Every time North Korea launches a missile, I wonder whether they’re using our technology, gained through Takemura.”

The two JAEA employees promised to get back to me as to whether, in 1972, PNC had been obligated to notify the IAEA and the government about its scientist’s disappearance.

Japan Atomic Energy Agency website (C)Tansa

Left to the Osaka police

The JAEA hadn’t known anything about Takemura’s disappearance, but maybe the Ibaraki Prefectural Police would be different. Tansa’s members searched for individuals who might be familiar with Takemura’s case.

One managed to locate a former Ibaraki Prefectural Police officer who had been chief of Hitachinaka-nishi Station (formerly named Katsuta, now Hitachinaka) in 2013. That year, the National Police Agency had released its potential abductee list, which noted Takemura as having been last seen in the station’s jurisdiction.

What’s more, this officer had also served as head of the Ibaraki Prefectural Police’s foreign affairs division, which dealt with espionage and other public safety issues.

A Tansa reporter visited his house. After they explained their interview request over the intercom, the former officer appeared in the doorway, clad in sweats.

“Did you receive permission from Takemura’s family before information about his case was published to the National Police Agency’s website in 2013?” our reporter asked.

“It never came up. [As chief] I would have been involved with that sort of thing, but I have no memory of it.”

“Takemura was from Osaka, and it’s our understanding that his family reported his disappearance to the Osaka Prefectural Police.”

“Well, if so, the Osaka police [would have handled the case].”

“But you also served as head of the Ibaraki police’s foreign affairs division,” our reporter continued. “Wouldn’t abductions and PNC’s security have been a matter of serious interest?”

“Yes, naturally I took an interest in those areas. Still do, in fact. But [Takemura’s case] never came up.”

“In 1972, after Takemura disappeared, a detective from Katsuta Station came to PNC to ask questions.”

“Is that so?” the officer replied. “This is the first I’m hearing of it. PNC’s security was part of my work, of course, but it was never connected with abduction. The case must have been dropped.”

“You have absolutely no memory of the name Tatsuya Takemura?”

“No, none.”

So the head of foreign affairs for the Ibaraki police had never heard that PNC’s plutonium expert had vanished.

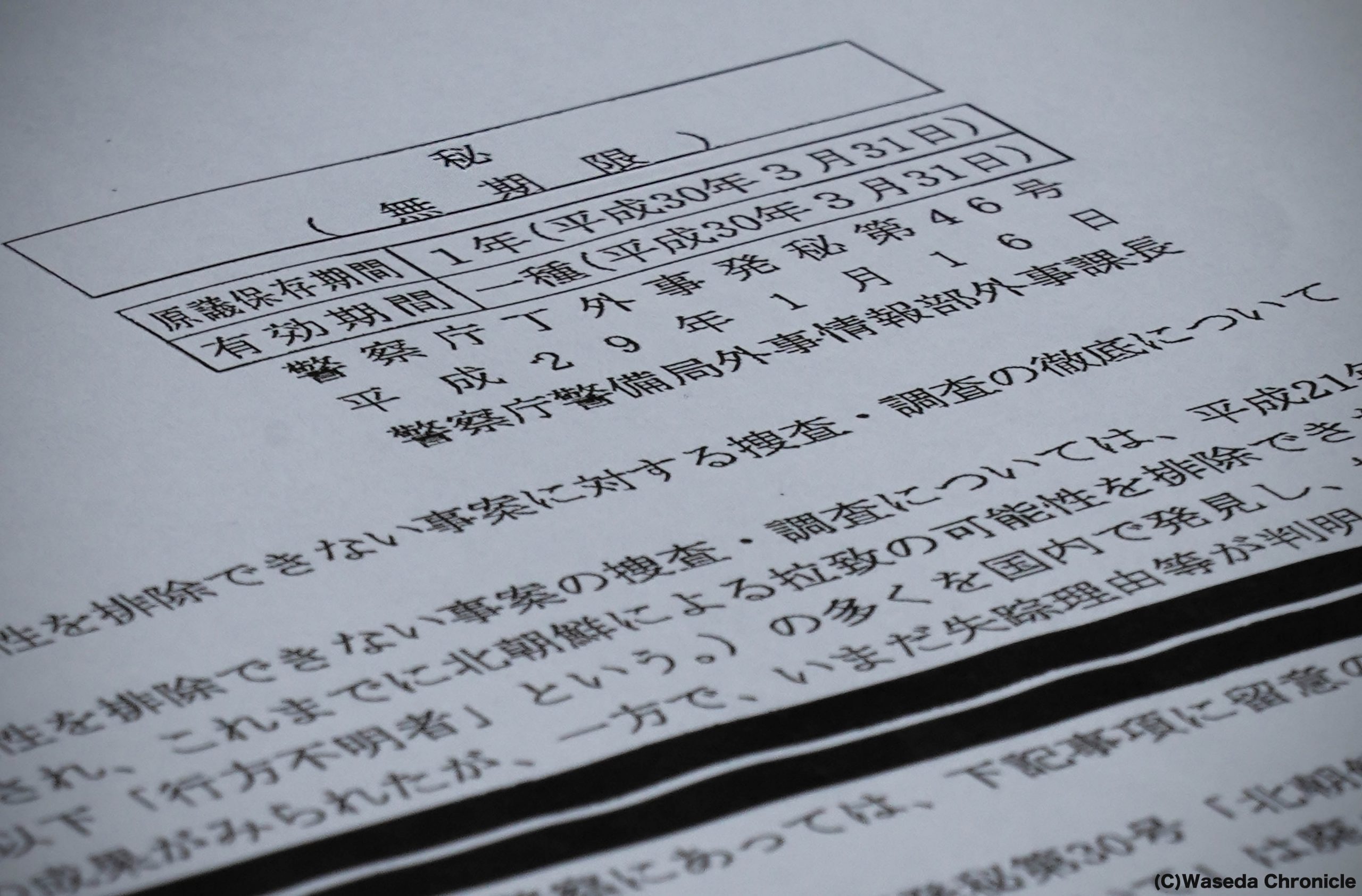

Directive sent by the National Police Agency to police nationwide, instructing them to thoroughly investigate potential abductions.

Confidential, redacted

Just how serious were the police about investigating Takemura’s disappearance?

Through a freedom of information request, I obtained a directive from the National Police Agency’s security bureau, foreign affairs and intelligence department. It had been sent to the head of the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department’s public security bureau and the heads of prefectural police.

Titled “Re thorough investigations into cases for which we cannot rule out the possibility of abduction by North Korea,” the directive was dated Jan. 16, 2017. It was marked “confidential (indefinite)” and began with the following.

“Since fall 2009, we have strengthened our initiatives related to investigating cases for which we cannot rule out the possibility of abduction by North Korea. Although we have seen some successes, including locating many such missing persons in Japan and ruling out the possibility of abduction in other cases, there are still numerous individuals for whom we are unable to determine the reason for their disappearance.”

The directive then gave three areas to pay particular attention to when conducting these “thorough investigations.”

The first, “Points to bear in mind,” was divided into four subcategories, including “Strengthening collection of related information and thorough analysis and inspection” and “Diligent execution of various types of inquiries and thorough guidance and instruction.”

But the majority of the content had been redacted. Among the four points, only “Appropriate response to families, etc.” wasn’t covered in black ink.

“Endeavor to appropriately respond with consideration for the feelings of the missing person’s family, etc.,” it read. “This includes explaining matters related to the investigation’s progress and discoveries, provided that information divulged does not hinder the investigation.”

The directive’s second area, “Thorough management by police headquarters and implementation of planned initiatives,” had been redacted in its entirety.

The third area was “Coordination with relevant agencies, prefectural police, etc.”

“Along with strengthening coordination with the Coast Guard and other relevant agencies, implement close, mutual coordination with the National Police Agency and other relevant prefectural police,” it read.

The directive had been so heavily redacted that my freedom of information request” lost most of its meaning. It provided little information on the police’s investigations into potential abductees like Takemura.

But at the very least, the directive had mentioned “close coordination” between police departments in different prefectures.

And yet, the former Ibaraki police foreign affairs division head had never even heard of Takemura’s disappearance. The most likely explanation was that the Osaka police, who were responsible for Takemura’s case, had never contacted their colleagues in Ibaraki about the matter.

It was hard to imagine that the police were serious about investigating the disappearance of this nuclear scientist.

… To be continued.

(Compiled from articles published in Japanese on May 13 and 15, 2020. Translation by Annelise Giseburt.)

———

What was North Korea’s objective in abducting Japanese citizens? Is Japan fit to handle nuclear technologies? With these questions in mind, Tansa is pursuing an independent investigation into the disappearance of former Power Reactor and Nuclear Fuel Development Corp scientist Tatsuya Takemura. This series is produced in collaboration with tabloid Nikkan Gendai, in which it is also published.

Get in touch with Tansa if you have information about the disappearance of Tatsuya Takemura. Please refer to our whistleblower support page for information on secure contact methods.

The Missing Nuclear Scientist: All articles

Newsletter signup

Newsletter signup