3,863 pesos in unpaid wages

2020.07.15 18:53 Hideaki Kimura

7 min read

The banana industry dominates the town of Compostela. There are few opportunities for employment outside the plantations and packing plants. Many leave Compostela for work abroad. Women are hired as maids in oil-rich Gulf Coast nations such as Saudi Arabia and Qatar, men as sailors on foreign vessels. These migrant workers help sustain the Philippine economy.

Melodina Gumanoy (43) serves as the secretary of joint labor union Namasufa, which is comprised of workers at banana producer Sumifru’s packing plants. Although she previously worked recording the bananas brought to the plant, Gumanoy has not received a salary since the union went on strike in October 2018.

As I spoke with her one morning, Gumanoy plucked branches from a moringa tree in her garden. Moringa, also known as the horseradish tree, is a popular food in the Philippines. Recently, it has come into vogue in Japan as well. Gumanoy reached up to snap off the tree’s thin branches. She was growing squash too. Her family depends on their little vegetable garden.

“We have no place to keep pigs, but even if we did, there’s no money for feed,” Gumanoy said. “It’s hard to find enough to eat. And we can’t afford to get sick.”

Melodina Gumanoy plucks branches from her moringa tree. Photo taken on Aug. 11, 2019 in Compostela, Compostela Valley (now Davao de Oro) Province, Philippines (C)Tansa

The work record

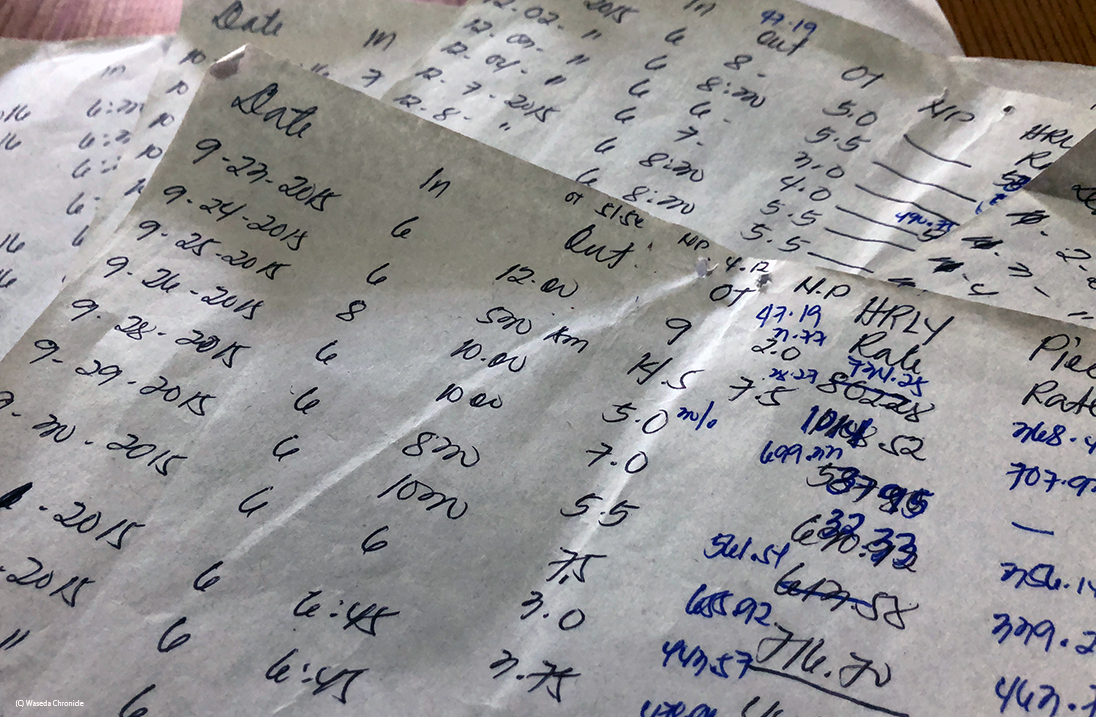

I was curious how much the union members had made before they were fired by Sumifru. When I asked Gumanoy, she said, “Hold on a minute,” and disappeared into her house. Moments later, she returned carrying a cloth handbag stuffed full of payslips and a handwritten record her work. It was obvious why Gumanoy was the union’s secretary.

Her notes, made in ballpoint pen on sheets of printer paper, chronicled the days when workers still were paid by commission rather than the legal daily minimum wage. The entries began on Sept. 23, 2015. Her notes from that day were as follows:

“Started work at 6 a.m., finished at midnight. Although I should have been paid for working at night and overtime, I only received 368.41 pesos (about $7). Unpaid wages amount to 365.84 pesos.”

Gumanoy had totaled her unpaid wages from Sept. 23 to Oct. 31, 2015, then added the figure to her document in red: 3,863.29 pesos (about $75). Roughly a fourth of the wages she was entitled to remained unpaid.

Melodina Gumanoy’s handwritten notes. Photo taken on Aug. 9, 2019 in Compostela, Compostela Valley (now Davao de Oro) Province, Philippines. (C)Tansa

The union, Gumanoy included, had protested the low wages workers received through commission-based remuneration. On April 24, 2017, workers at last began to be paid the legal daily minimum wage.

Before she was fired for participating in the strike, Gumanoy earned about 365 pesos (about $7) per day, the daily minimum wage. There was no hourly rate. Overtime pay was added to the daily minimum. However, the work was not constant. Gumanoy usually only worked at the packing plant three days per week.

Wages were paid every 15 days. Insurance and social security fees were deducted from the total. According to Gumanoy’s payslips for roughly the first year after workers began to be paid the daily minimum wage, her take-home pay every 15 days was between 3,048.48 and 5,373.79 pesos ($59 to $104). The average was about 3,700 pesos ($71).

No matter how low the cost of living may be, that is not enough to support a family.

A banana plantation at dawn. Photo taken on Aug. 9, 2019 in Compostela, Compostela Valley (now Davao de Oro) Province, Philippines. (C)Tansa

Continuing her education

Gumanoy lives with her husband (47) and two daughters.

They consume 10 kilograms of rice, the staple food in the Philippines, per week. The typical white rice sold in the Compostela market costs 39 pesos per kilogram. A week’s worth costs 390 pesos, one day’s pay.

“We need rice, even if we don’t have anything to accompany it,” Gumanoy said. Her mother helps out when they don’t have enough.

Gumanoy currently relies on her husband’s income. He works six days per week at a relative’s banana plantation. The daily pay is 300 pesos, less than the 365-peso minimum wage. When Gumanoy worked at the packing plant, she often asked for advances on her salary. During the commission-based remuneration days, there were times when her take-home pay was practically nothing. She borrowed. As long as Gumanoy is unemployed, she can’t pay back what she owes. Her union position is voluntary.

Gumanoy’s younger daughter attends public elementary school; her uniform costs 700 pesos per year, with an additional 500 pesos for gym clothes. The elder daughter (21) wanted to continue her education and attended university in Compostela. A relative who works as a watchman at a banana plantation not owned by Sumifru helped cover her tuition. She earned a bachelor’s degree in education and has worked in Compostela as a teacher since 2017. Her monthly salary is about 8,000 pesos, from which she gives her younger sister a 20-peso daily allowance.

When money was especially tight, Gumanoy worked as a nanny for relatives living in the suburbs of Manila, the capital.

Gumanoy is by no means the only one to go into debt to keep her family afloat. They don’t borrow to purchase luxury items — the wages paid by Sumifru are simply not livable. Workers fired for participating in the strike are unable to repay their debts.

Take union member Marcial Lanticse (34), whose family includes his wife (26), three sons (7 years, 6 years, and 2 months), and daughter (1). Six months before he was fired, Lanticse borrowed 18,000 pesos through the social security system. He had to pay back 932 pesos per month for two years. Lanticse currently works as a harvester at a small banana plantation not owned by Sumifru. There is only enough work for him two or three days per week. The pay is commission-based, and Lanticse only earns between 200 and 300 pesos for a 6 a.m. to 6 p.m. shift. They had previously hired a nanny at 500 pesos per week, but as Lanticse’s wife was also fired by Sumifru, they can no longer afford the expense. The family buys daily necessities on credit. The store owners know they are participating in the strike, so they agree to defer payment until Lanticse and his wife can return to work again.

Rice, a staple food in the Philippines, sold in the market. Various kinds of rice are sold in the market, as well as corn (bags in the front row). Photo taken on Aug. 9, 2019 in Compostela, Compostela Valley (now Davao de Oro) Province, Philippines. (C)Tansa

Circles on the calendar

Initially, Sumifru refused to negotiate with Namasufa. In late November 2018, Gumanoy and other union members went to Manila to petition central government agencies to force Sumifru to negotiate with them.

Gumanoy’s young daughter missed her mom. “I’ll be home by Christmas,” Gumanoy promised. With a pencil, her daughter drew a dark circle around Dec. 25 on the calendar. But Gumanoy couldn’t make it back. This time, she said, “I’ll see you at New Year’s.” Her daughter circled Jan. 1, 2019. But Gumanoy had to break her promise again. At their tent in central Manila, the union members continued their protest. Gumanoy’s daughter next circled her birthday, Jan. 21, but her mom still couldn’t come home.

Gumanoy made a final promise to her daughter: “If you get an honors medal for your grades in school, everyone in the family will escort you at the end of term ceremony.”

The ceremony was on April 2. Gumanoy’s daughter had kept her promise — a six-centimeter plastic medal strung with red ribbon hung proudly around her neck, proclaiming that she was among the top 10 students.

But Gumanoy wasn’t there to hold her daughter’s hand and escort her at the ceremony. She could only return home on April 18, 16 days later.

The honors medal Melodina Gumanoy’s daughter was awarded. Photo taken on Aug. 11, 2019 in Compostela, Compostela Valley (now Davao de Oro) Province, Philippines. (C)Tansa

… To be continued.

Ages are given as of the time of interview. Investigative partners: Alternative People’s Linkage in Asia, Friends of the Earth Japan, Pacific Asia Resource Center (PARC)

(Originally published in Japanese on Aug. 22, 2019)

Sweet Bananas, Bitter Work: All articles

Newsletter signup

Newsletter signup