1.2 million DNA profiles in police database

2020.05.20 20:41 Makoto Watanabe

5 min read

Japan’s National Police Agency is eagerly gathering citizens’ DNA.

Often called the body’s blueprint, DNA contains genetic information unique to each individual. In a sense, it is our most intimate personal information. Collection is simple: Just rub the inside of the cheek with a cotton swab.

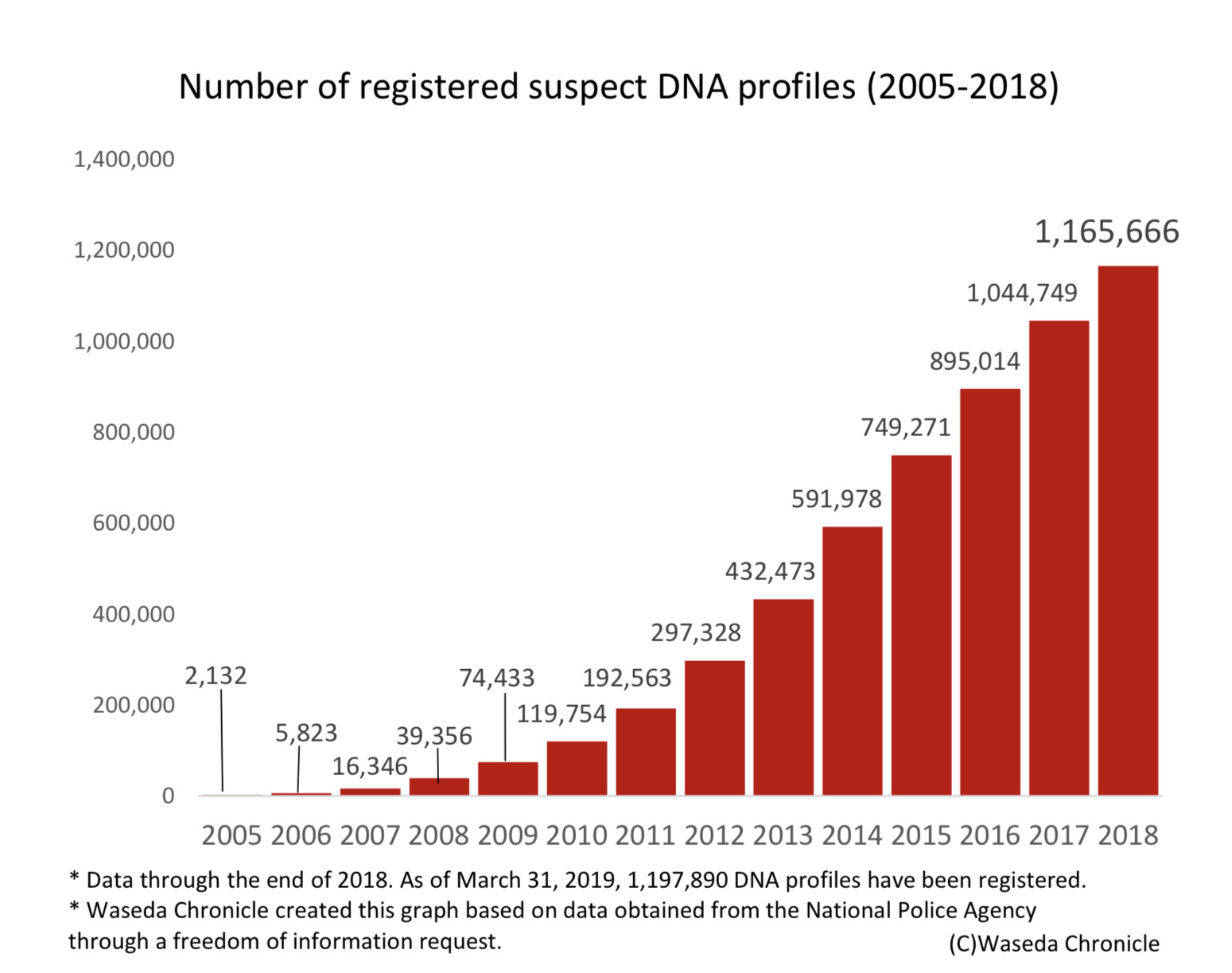

The NPA has been building a database of “suspect DNA gathered during investigations.” It contains the profiles of almost 1.2 million individuals and continues to grow. Out of Japan’s population of roughly 127 million, the police have every one in 100 people’s DNA on file.

But are there really 1.2 million suspected criminals in Japan?

In fact, the police collect DNA for minor offenses too.

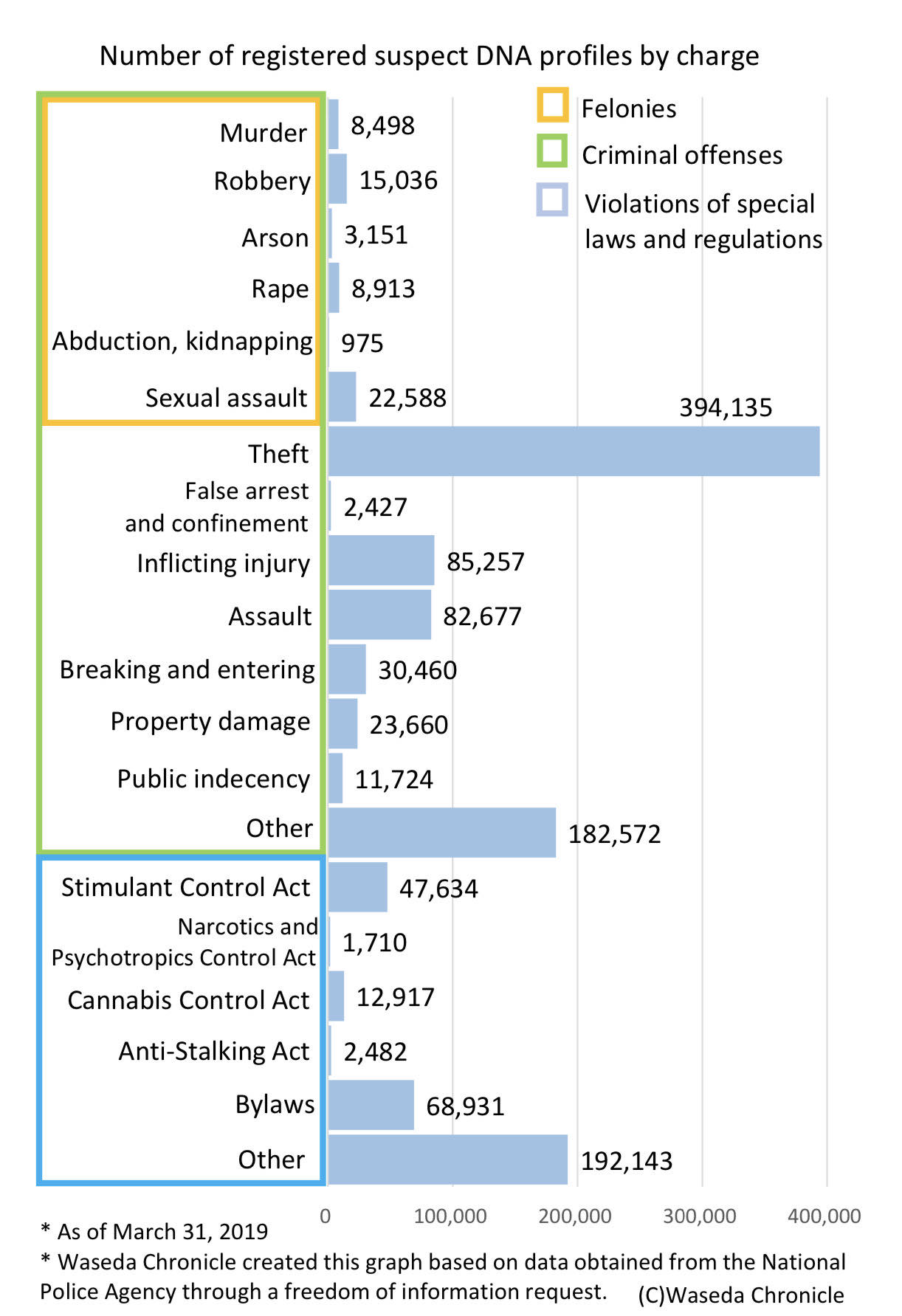

Of the 1.2 million DNA profiles, only 59,161 were collected in connection with felonies such as murder or sexual assault — less than 5% of the total.

Tansa learned the composition of the NPA’s database from police documents obtained through a freedom of information request. The documents list the number of DNA profiles by offense. With 374,715 total profiles, DNA collected in relation to unspecified “other” offenses and violations of special laws and regulations outnumber felony DNA by more than six to one. The “other” category includes petty crimes such as violations of the Minor Offenses Act.

In one case, an individual’s DNA was taken just for putting up “lost dog” posters on telephone poles.

National Police Agency documents divide crimes into “criminal offenses” and “violations of special laws and regulations” such as bylaws. Six criminal offenses, such as murder and arson, are classified as “felonies.”

Even if a suspect is not prosecuted for a crime, they have no way of knowing whether their DNA has been deleted from the database.

The NPA’s stated reason for creating the database is “for use in criminal investigations.”

But something isn’t right: No law regulates DNA collection and storage. It is left up to the police’s discretion.

Why hasn’t such a law been created? What will happen if the police’s access to our DNA remains unchecked?

We wanted to hear from people who have had their DNA collected by the police.

In 2019, a young man in Aichi Prefecture had his DNA collected simply because he went fishing.

Hopping the guard rail

Shota Uchino (an alias) was stopped by the police on Jan. 3, 2019.

Around 2 p.m. that day, Uchino was fishing in an irrigation channel in the Moriminami neighborhood of Ama City, Aichi Prefecture. The channel was a popular spot for catching black bass.

Uchino is in his 20s. Mental health problems had forced him to leave his job three years prior, and since then he had been recovering at home. By January 2019, Uchino was on the mend and thinking of looking for work again. On the third, he had driven to the irrigation channel to spend some quality time fishing.

As it was still the New Year’s holiday, there were no other fishers. Uchino cast his rod from a bridge that spanned the channel, plopping the lure into the water.

But the bass weren’t biting. Uchino decided to try casting from the channel’s bank.

He hopped the 85-centimeter guard rail that bordered the channel and descended the concrete levee to the water’s edge.

Still no bites. Giving up on bass for the day, Uchino turned away from the water and was about to climb back up the levee.

“Wait a second,” a voice suddenly called out behind him.

Uchino turned to see a police officer mounted on a motorcycle about eight meters away on the opposite bank.

“This probably calls for an arrest”

The tall, young police officer parked his motorcycle on the opposite bank and approached Uchino.

“Don’t you know this area is off-limits?”

“No, I don’t,” Uchino said. It was the truth.

A guard rail ran along the channel for about nine meters before being replaced by a chain-link fence 1.15 meters high. A “do not enter” sign was affixed to the fence, not to the guard rail Uchino had climbed over. When we visited the area, the 60-by-45-centimeter sign was hidden behind a thicket of weeds.

On January 3, Uchino hadn’t noticed the sign at all.

“Have you been here before?” the officer asked.

“Five or six times,” Uchino replied honestly.

This was the first time he had crossed the guard rail to approach the water, but he often went fishing in the area. After all, it was a popular spot to catch black bass. “Everyone goes fishing here,” he added.

The police officer returned to his motorcycle and picked up his two-way radio. He appeared to be calling for backup.

Uchino’s anxiety grew. His heart was racing.

“What’s going to happen to me?” he asked.

“This probably calls for an arrest,” the officer replied.

The 'do not enter' sign attached to the chain link fence bordering the irrigation channel. (C)Tansa

Escorted to the station by two motorcycles and a police car

Uchino was scared.

“What’s going to happen?” he asked again.

“You might be arrested,” the officer replied this time.

About 20 minutes later, another young, male police officer arrived on a motorcycle.

The second officer made Uchino stand in front of the fence and point at the “do not enter” sign while he took a photo.

He also took a photo of Uchino pointing to the levee bank where he had been fishing. Then another of Uchino standing next to his car, holding his fishing rod.

Before long, a police car arrived.

Two older men joined the group. Uchino was now surrounded by four officers.

He told them he suffered from mental health problems, but they didn’t seem to care.

Although they didn’t arrest him, the officers asked Uchino to come with them to Tsushima Police Station for questioning. It was about 15 minutes away. Uchino drove his own car, with the two motorcycles in front and the police car behind him. One of the officers instructed them to drive in that formation, although he said he “didn’t think Uchino would try to run.”

Uchino’s heart beat frantically. His hands, gripping the wheel, were slick with cold sweat.

He felt sick.

… To be continued.

(Originally published in Japanese on Sept. 5, 2019)

On the Hunt for DNA: All articles

Newsletter signup

Newsletter signup