Why Japan doesn’t have until 2050 to go carbon neutral

2021.10.07 13:55 Annelise Giseburt

Members of Youth4ClimateAction in front of South Korea's constitutional court on March 13, 2020. (C) Youth4ClimateAction

As explained in our previous article, lawyers for Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry initially tried to deny their own data and claim ignorance of basic climate science in a lawsuit that aims to stop the construction of coal plant in the city of Yokosuka.

A member of the plaintiff group, which includes residents from Yokosuka and neighboring towns, speculated that the government lawyers’ careless attitude came from confidence in their own victory.

But, looking at climate litigation around the world, a government victory isn’t always assured. In recent years, citizens, lawyers, and environmental groups have repeatedly used the courts to impel their governments to take stronger stances on climate.

The world has seen over 1,800 climate cases in roughly 40 countries, and the number continues to rapidly grow. Of 369 decided cases analyzed by the Grantham Research Institute, roughly 60% had outcomes favorable to climate change action.

In numerous instances, their success lies in a concept little discussed in Japan: our rapidly dwindling carbon budget.

Over 1,000 climate lawsuits filed since 2015

In July 2021, Joana Setzer and Catherine Higham of the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment released a report analyzing trends in climate litigation around the world.

Of the 369 decided cases examined, the report found that 118 had outcomes unfavorable to climate change action, such as failed challenges to approvals for new high-emission projects. Thirty-six cases had no discernible impact. But the majority — 215 cases — had outcomes favorable to climate action, such as a high-emission project stopped or emission reduction targets strengthened.

Between 1986 and 2014 roughly 800 climate cases were filed. In just six years since 2015 there have been more than 1,000 new cases.

The report notes that “climate change litigation continues to grow in importance as a way of either advancing or delaying effective action on climate change.”

Here are a few examples of successful climate litigation.

・Netherlands: In September 2013, the climate activist group Urgenda Foundation sued the Dutch state, arguing the government had ignored the short-term emission reduction targets it itself had previously said were necessary. Urgenda saw victories in the district court, court of appeals, and finally the supreme court in 2019.

・France: In March 2019, environmental nonprofits sued the government over its climate policies. In February 2021, the Administrative Court of Paris ruled that the government’s failure to reduce short-term emissions was causing unlawful environmental harm through climate change.

・Colombia: In January 2018, Colombian youth sued the government, claiming that its failure to sufficiently reduce emissions and prevent deforestation was harming their fundamental rights. The supreme court ruled in their favor in April 2018.

・Nepal: In August 2017, an environmental lawyer filed a petition that aimed to force the government to enact a comprehensive climate change law. In December 2018, the supreme court ruled that the government’s failure to address the climate crisis violates fundamental constitutional rights, as well as its commitments under the Paris Agreement.

Members of the Urgenda plaintiff group in front of the Dutch supreme court. Photo taken in December 2019. (C) Chantal Bekker

“Irreversibly offloading the burden”

A number of recent climate cases highlight the impact of the climate crisis on youth.

Germany is one such example. On April 29, 2021, Germany’s Federal Constitutional Court issued a ruling that, roughly a week later, prompted the government to promise to raise the country’s emission reduction targets.

The suit was brought to the constitutional court by nine German youth, including one of the leaders of environment activist group Fridays for Future.

The constitutional court ruled that “the Federal Climate Change Act governing national climate targets and the annual emission amounts allowed until 2030 are incompatible with fundamental rights insofar as they lack sufficient specifications for further emission reductions from 2031 onwards.

“The challenged provisions [of the Climate Change Act] do violate the freedoms of the complainants, some of whom are still very young. The provisions irreversibly offload major emission reduction burdens onto periods after 2030.”

Germany’s remaining carbon budget was a motivating force behind the court’s decision.

The term “carbon budget” refers to the upper limit of total CO2 emissions that we can still emit before exceeding a specific global average temperature. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) sixth assessment report, released in August 2021, we have just 11.5 years until we use up the remaining carbon budget for keeping global warming under 1.5 degrees C (50% probability; at 2020 levels of emissions).

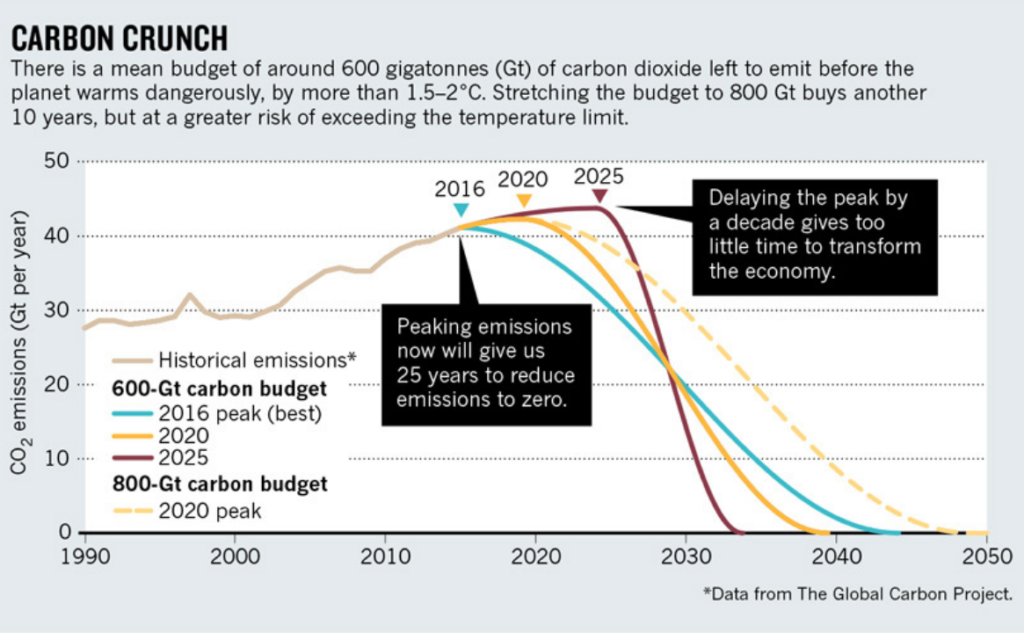

A graph from a June 2017 article in Nature (Figueres et al.) illustrating how delaying emission reductions will mean we need to make more drastic cuts sooner. Graph source: Stefan Rahmstorf/Global Carbon Project

In its decision, the German constitutional court referred to the country’s own remaining carbon budget, calculated by the German Advisory Council on the Environment based on IPCC estimates. The council found that Germany’s carbon budget would be “largely used up by the year 2030.”

Dennis van Berkel, a legal counsel for the Urgenda Foundation who was part of its pioneering climate lawsuit in the Netherlands, explained the ramifications of Germany’s carbon budget calculation. Once the budget is depleted, Germany would have to suddenly reduce its emissions to almost zero within a year in order to stay Paris-compatible.

“The court decided that it’s a massive restriction on the freedom of people after 2030,” van Berkel says. “You wouldn’t be able to go out, drive your car, heat your house — it’s unimaginable. The court decided that’s unconstitutional because it’s unduly burdening people in the future.

“It was the inevitable conclusion that Germany had to increase its 2030 emission reduction target.”

Although the constitutional court didn’t mandate any specific new targets, on May 5, 2021, the German government announced its intention to raise its 2030 emission reduction target from 55% to 65%.

The German court’s decision reverberated in Asia too, with a group of youth plaintiffs and their lawyers who had filed a suit in South Korea’s constitutional court in March 2020. They claim their country’s 2030 emission reduction target fails to prevent future harm to their generation.

Although their initial complaint didn’t focus on South Korea’s carbon budget, Sejong Youn, a legal counsel for the plaintiffs, said their team was inspired to calculate what that budget is following the victory in Germany.

“The population of Korea is smaller than Germany, but our annual emissions are pretty much the same right now,” Youn says. “We found Korea’s carbon budget will be depleted in three years.”

Yokosuka legal team: “Japan’s carbon budget used up by 2025”

Back in Japan, the Yokosuka plaintiffs’ legal team also recently highlighted carbon budgets in its argument. At the Tokyo District Court on Sept. 3, 2021, the lawyers presented the judge with their calculation of Japan’s remaining carbon budget. The team based its calculations on population, as both the German advisory council and the South Korean lawyers had done.

According to the lawyers, Japan will use up its remaining 1.5 degree C carbon budget in 5.8 years if it continues emitting at 2018 levels — in other words, by 2025.

JERA, the utility that owns the new Yokosuka coal plant, does not appear to be working within the same time frame.

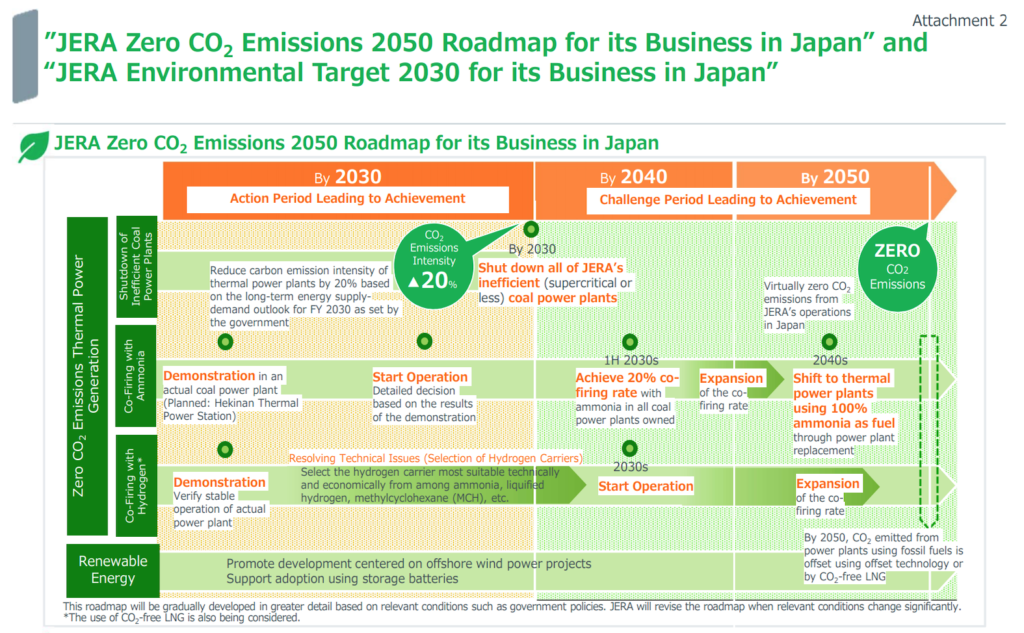

It declared its intention to go carbon neutral by 2050 in October 2020, shortly before the prime minister made the same commitment for Japan overall. As part of that announcement, JERA released a roadmap for how it will make its thermal power stations zero emission. The utility said it would gradually replace coal with ammonia, utilizing mixed combustion for most of the period from the late 2020s to 2050.

JERA aims to run coal plants like Yokosuka on 20% ammonia, 80% coal by the early 2030s. As ammonia doesn’t emit CO2 when burned, this would mean the Yokosuka plant’s annual CO2 emissions would be reduced from 7.26 million tons to 5.81 million tons.

JERA hopes to achieve a 20% reduction in emission intensity across its thermal power generation portfolio by 2030.

JERA's plan to decarbonize by 2050, announced on Oct. 13, 2020. Graphic taken from its press release.

In addition to JERA’s plan seeming rather relaxed from a carbon budget perspective, Japan’s own Agency for Natural Resources and Energy has admitted that running all of Japan’s coal plants with 20% ammonia would require almost the entirety of the world’s current ammonia trade volume.

In response to questions from Tansa, JERA stated the following about its plans for decarbonization.

“Although there are still many technological barriers that we must overcome to achieve ‘JERA Zero Emission 2050,’ we will continue to actively develop our decarbonization technology in order to do so.”

Around the world, an increasing number of lawsuits are putting lax climate policies and high-emission projects to the test.

It’s possible that the Yokosuka plaintiffs will be among those pulling us back from climate catastrophe. But with no successful domestic precedents, it’s difficult to say how their suit will fare. A decision from the Tokyo District Court isn’t expected until sometime in 2022.

In the meantime, construction of the coal plant continues.

The new Yokosuka coal-fired power plant, currently under construction, is scheduled to fully come online in 2024.

—————

This article is supported by the Judith Neilson Institute’s Asian Stories project, in collaboration with the Australian Financial Review, the Centre for Media and Development Initiatives Vietnam, the Korean Center for Investigative Journalism Newstapa, Malaysiakini, Tempo, and Tortoise Media.

Newsletter signup

Newsletter signup