Seniors, including individuals with dementia, coerced into newspaper subscriptions

2021.03.12 13:53 Makoto Watanabe

Multiple newspaper subscriptions taken out by one 84-year-old woman

“Mom, why’re you subscribed to so many papers?”

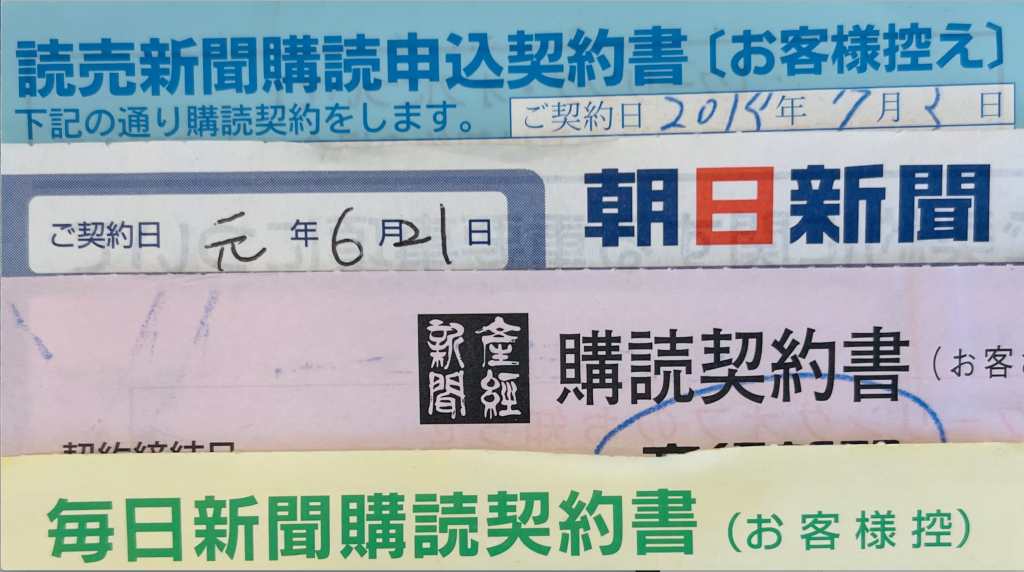

In September 2019, a woman (45) was surprised to find a modest stack of contracts sitting beneath the landline in her mother’s apartment in Tokyo’s Kita City. The contracts were subscriptions to four of Japan’s major papers: the Yomiuri, Asahi, Sankei, and Mainichi.

“Maybe there was some mistake?” replied her mother (84), suddenly confused and worried. She was showing signs of dementia and was increasingly forgetful.

The woman took a closer look at the four contracts. Some had overlapping subscription periods, and some were even set to begin in three years’ time. She became increasingly indignant: Her mother lived in municipal housing and supported herself on pension payments of a mere 110,000 yen (about $1,050) per month. A subscription even to just the morning edition of a single paper came with a monthly fee between 3,000 and 4,000 yen (about $29–38).

Her mother had said she wanted a paper delivered to help her keep track of the date, but four was totally excessive.

The woman lost no time calling each paper’s distributor to cancel the subscriptions. “My mother suffers from forgetfulness; she can’t make an informed decision to take out a subscription. Please let her cancel it.”

Sankei responded as asked. But when the woman called the Yomiuri, she was told “We need to recover the cost of the rice gifted when the contract began, so please continue the subscription for one more month.” The Asahi distributor too said that cancellation was dependent on the return of a free catalogue that had come with the subscription.

As for the Mainichi, although the woman managed to cancel, a solicitor visited her mother again in March 2020. This time, the woman called the Mainichi’s head office rather than the distributor.

“A salesman came around with a hard sell last year too. I already explained [to the distributor] that my mother has a bad memory and asked them to stop. If we want a paper, we’ll say so.”

At last, the Mainichi left her mother alone.

Incidents of elderly individuals coerced into taking out subscriptions to newspapers occur throughout Japan. Even in a single month (January 2020), consumer affairs centers across the country received over 100 complaints specifically related to newspapers and the elderly. These complaints are often submitted by elderly individuals’ family members or caretakers.

But it’s much harder for those without a support system to seek remediation. Cases reported to consumer affairs centers could be just the tip of the iceberg.

As readerships steadily decline, Japan’s newspapers finds themselves in an increasingly dire financial situation. Tansa investigated the lengths to which they will go to save themselves from going under.

“He even calls in my dreams”

A man (84) living in prefectural housing in Osaka Prefecture’s Sakai City had been receiving visits and calls from a Yomiuri solicitor for roughly a year.

Having suffered from poor health since he was a child, the man hadn’t been able to work enough to receive a livable pension. Supported by welfare payments, he certainly didn’t have the financial leeway to subscribe to a paper.

But the solicitor wouldn’t take no for an answer and kept calling. Feeling hounded, the man started having dreams in which the solicitor would pressure him to take out a subscription. In the end, he reluctantly caved, just to relieve the stress.

The man asked his daughter (51) for help. She called the Yomiuri distributor from her father’s phone and explained that he wanted to cancel the subscription. The distributor said they would call her back at her own number and hung up.

But when the call came, it was to the man himself, not his daughter. The distributor said that cancellation was only possible after another six months, and the man folded.

His daughter was furious when she heard. She called the distributor again: “Pressuring an old man in poor health to take out a subscription is just fucking unbelievable!”

Although she finally managed to cancel the subscription, the distributor parted with “Promise not to subscribe to any other papers.”

But it didn’t end there. She happened to take a call while visiting her father — it was the Yomiuri solicitor. “What the hell! I told you never to call again,” she said angrily and hung up. But the damage was done: Her father was on edge, anticipating calls from the solicitor, and she worried about the emotional toll it was taking on him.

“Two copies of the same paper,” “suspicious handwriting,” “dressed as a delivery man” — and more

Tansa sent a freedom of information request to the National Consumer Affairs Center of Japan for records of complaints from consumer affairs centers across the country related to newspaper soliciting. In order to get our request processed in a reasonable amount of time, we started with records just from January 2020.

That one month had seen about 300 complaints related to newspaper soliciting. Among them, 106 cases related specifically to elderly individuals being targeted by hard sells or being unable to cancel their contracts. A few cases related to individuals with disabilities. The following are 11 particularly egregious examples.

1. “A newspaper sales agent came to my mother’s home dressed as a delivery man. My mother thought nothing of it and signed the contract. It’s underhanded.”

2. “I wasn’t allowed to cancel my relative’s subscription, even though I explained that they were about to enter an intensive-care retirement home.”

3. “My elderly parents suddenly starting having a newspaper delivered to their home in January. I tried to call to cancel, but was told to return the 20,000-yen (about $190) gift certificate.”

4. “I have glaucoma, so it’s hard for me to read, but I wasn’t allowed to cancel my subscription.”

5. “My brother-in-law, who has a mental handicap, took out a newspaper subscription two years ago, but it just started being delivered this month. He wasn’t aware that he had taken out the subscription, but I wasn’t allowed to cancel it.”

6. “I work in a care facility, and one of our clients, who has dementia, was pressured into taking out a subscription. I’m trying to negotiate on their behalf to get it cancelled, but it makes me uneasy.”

7. “My older sister, who is elderly and lives alone, isn’t up to reading the paper. A subscription contract that didn’t include either a name or address was delivered to her house. I want to cancel it.”

8. “I paused my husband’s newspaper subscription for about nine months because he had been hospitalized. He ended up passing away, and my eyes aren’t strong enough to read the paper, but I was made to continue the subscription due to ‘time remaining in the contract.’”

9. “My wife, who has poor eyesight and shows signs of dementia, took out a subscription, and now we receive two copies of the same regional paper. One is enough, but the distributor won’t respond to our request to cancel the second.”

10. “Today I discovered that my mother had taken out a newspaper subscription from a solicitor, but the subscription term will begin two years from now. Her address was pre-printed in the contract — I’m furious.”

11. “My elderly mother, who lives alone, gets a paper delivered to her home, but the handwriting on the contract doesn’t look quite like hers.”

Newspaper circulation fell by 2.7 million in one year

In Japan, readers don’t take out newspaper subscriptions directly from the papers themselves: They enter into a contract with an independent distributor, which has purchased a certain number of copies from the paper. Solicitors making phone and house calls are employed by newspaper distributors.

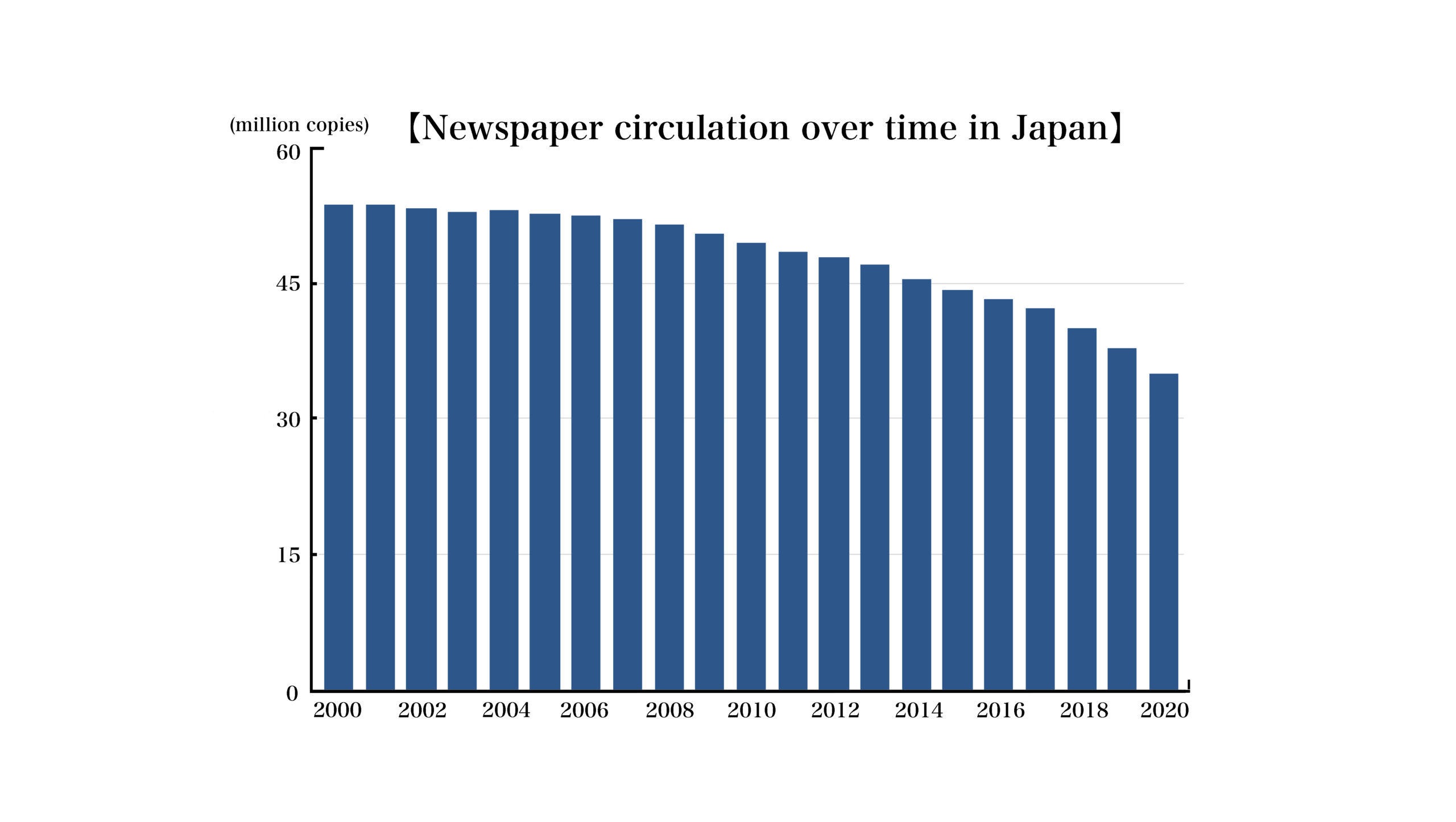

In 2020, total circulation of all national, regional, and sports papers in Japan was at about 35.1 million copies. That’s a 35% decrease from 2000, when circulation numbers were around 53.7 million. It isn’t hard to imagine that this dramatic dip has helped spur the questionable sales tactics described above.

The decrease in circulation numbers has accelerated in recent years, with 2020 seeing a roughly 2.7-million-copy drop from the year before. Based on the current trend, circulation may decrease even more rapidly in the future.

Compiled by Tansa from statistics on the Japan Newspaper Publishers & Editors Association’s website

Japan Newspaper Publishers & Editors Association “not investigating any specific cases”

How do Japan’s newspapers view these coercive sales tactics, the victims of which are often elderly individuals with dementia or poor eyesight?

On Dec. 21, 2020, Tansa requested comment from the Japan Newspaper Publishers & Editors Association, which is comprised of 103 papers across the country. Our questions, addressed to association President Toshikazu Yamaguchi (president of the Yomiuri Shimbun Group), were as follows.

1. Is the Japan Newspaper Publishers & Editors Association aware that some of its member papers employ questionable sales tactics toward elderly individuals, including those with dementia?

2. If the association is aware of said sales tactics, what concrete countermeasures have been implemented?

3. Are these questionable sales tactics in line with the Specified Commercial Transactions Act and other laws governing newspaper soliciting? If you believe these sales tactics are lawful, please state your reason.

Although we gave a deadline of Dec. 24, 2020, an association spokesperson replied that the association needed a little more time to consider its response.

We heard back in the new year, on Jan. 18, 2021. The response was given in the name of Japan Newspaper Publishers & Editors Association managing director Fumiaki Nishino.

To our first question of whether the association was aware of questionable sales tactics used to coerce elderly individuals into taking out subscriptions, the association replied as follows.

“Although the association is aware of consumer trouble involving elderly individuals from materials released by the National Consumer Affairs Center, we are not investigating any specific cases.”

“Materials released by the National Consumer Affairs Center” referred to a press release from the center titled “Consumer trouble with individuals 60 and above in fiscal year 2019.” It compiled complaints related to various products purchased by elderly individuals, including the following case related to newspapers and an elderly individual with dementia.

“My mother subscribed to Newspaper A, but for the past five years — from the end of her subscription period until this month — she subscribed to Newspaper B. She didn’t really read it, so she was relieved when the subscription period finally ended.

“But yesterday, a letter arrived from the Newspaper A distributor, saying that the morning edition would be delivered for the next three years starting next month. My mother has no memory of re-subscribing to the paper, but when I asked the distributor, they said that five years ago she had signed a three-year contract that will begin next month. They said they had the signed contract on file, and they later brought over a copy. While it matched my mother’s handwriting, recently she has been showing signs of dementia, and she wants to cancel the subscription in any case. I hope it can be resolved.”

(Received in December 2019. Complaint received from: woman, 60 years old. Subscriber: woman, 80 years old.)

Nevertheless, the Japan Newspaper Publishers & Editors Association took no action to follow up on this kind of case. It was simply written off as “trouble with consumers.”

However, “trouble” is a misrepresentation: It bothsides the issue and makes such cases seem like isolated disputes.

But the reality is that elderly individuals with dementia are being taken advantage of.

No response as to whether sales activities follow the law

Our second question was whether the association had implemented any specific countermeasures to combat questionable sales tactics.

The association’s response: “A report was made to the association’s sales committee (comprised of officers in charge of sales from 59 newspapers) regarding the materials released by the National Consumer Affairs Center. It was also shared with distributors and their solicitors across the country, who were told to be more careful of consumer trouble, especially with the elderly.”

In other words, distributors and their solicitors had only been told to avoid trouble; no further action had been taken.

The association replied to our third question, whether such sales activities were in line with the Specified Commercial Transactions Act and other relevant laws, as follows.

“The association calls on all distributors and their solicitors across the country to always abide by sales regulations such as the Specified Commercial Transactions Act, and the decline in complaints can be seen as a result of such.”

Without answering whether or not these newspaper sales activities were following the law, the association only noted that it “called on” distributors and their solicitors to always do so.

“The decline in complaints” referred to those related to newspaper sales activities received by consumer affairs centers across Japan in fiscal year 2019. At 6,267 cases, it was 1,086 and 3,906 cases lower than in fiscal years 2018 and 2013, respectively.

But the association appeared not to see the recent figure of 6,000-plus cases as an issue in itself. With regard to elderly individuals with dementia or a low income being coerced by aggressive sales tactics, the association indicated no particular opinion.

(Compiled from articles originally published in Japanese on Dec. 28, 2020 and Jan. 25, 2021. Translation by Annelise Giseburt.)

Shady Subscriptions: All articles

Newsletter signup

Newsletter signup