The reality of “high-quality infrastructure exports”

2018.11.05 21:54 Makoto Watanabe

Cirebon 1 coal-fired thermal power plant , West Java, Indonesia, Sep. 2, 2018 (C)Tansa, KCIJ Newstapa, Tempo

Why are countries with some of the world’s most advanced anti-pollution technologies building power plants in Indonesia that would not meet standards at home?

Why wouldn’t Japan use its advanced anti-pollution technology overseas?

Coal-fired thermal power stations are being built as a joint project of Japanese and South Korean trading and electric power companies. One, which has already started operating in Indonesia, cannot meet Japanese or South Korean pollution control standards. The Japanese, South Korean and Indonesian governments have ignored local voices of protest.

The multi-billion-yen power plant project is located in the West Java region of Cirebon. Unit 1 started operating in 2012 and the second and third units, called Cirebon 2 and Cirebon 3, are scheduled to be built. Cirebon 1 cost ¥96 billion (about $848 million). The estimated cost of Cirebon 2 is about ¥226 billion (about $1.9 billion) and the third unit of the project is likely to be as expensive.

The chief operator of the project is a company that Japanese trading giant, Marubeni Co., has created in Indonesia. The project is financed by the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) which is 100 percent backed by the Japanese government, working in tandem with a South Korean electric power company and a bank.

The project has a grave defect: it would not pass pollution control standards in Japan and South Korea. Indonesia’s less stringent standards and regulations allow it to go ahead. Since anti-pollution technology is not required, the project may be about 20 percent less expensive than if it were built in Japan or South Korea, according to an expert.

Local residents are furious.

Local residents were furious and asked us if other countries think it’s ok for Indonesians to suffer from pollution.

Many countries are shifting to non-coal-fired thermal power generation to abide by the Paris Agreement, which was adopted to reduce global carbon dioxide emissions. Financial institutions around the world have also stopped financing coal plants.

Yet, politicians and businesses in Japan, South Korea, and Indonesia are snubbing this global trend and still promoting environmentally harmful power plant projects, despite protests from local residents. Why?

Tansa investigated this issue together with KCIJ Newstapa, a South Korean non-profit news organization; and Tempo, an Indonesian news organization. Our joint investigative reporting project aims to uncover the truth about an issue that should concern us all.

You can read related articles by Newstapa here.

Map of the coal-fired thermal power plant in the West Java region of Cirebon, Indonesia

We were watched by police while we reported on the anti-power plant movement

The coal-fired thermal power plant stands in the Kanci Kulon village in the Cirebon region, about 250 kilometers from the Indonesian capital of Jakarta. The village has a population of 7,000 people.

Cirebon 1 has been operating since 2012, generating 660,000 kilowatts an hour. Cirebon 2 will generate 1 million kilowatts. The scale of the project may be judged by the fact that some of the biggest Japanese power plants in Japan – in Minamisoma city in Fukushima Prefecture for example, and Misumi town in Shimane Prefecture ー also generate 1 million kilowatts.

Tansa drove four hours from Jakarta to the village with representatives from a non-governmental organization called WALHI on Aug. 31, 2017. Locals make their living by catching clams and shrimp, growing green peas and cassava, and from salt production.

We talked to residents who have opposed the power plant project.

The salt farm right next to the power plant creates a staple industry in the region, Sep. 2, 2017, Cirebon, West Java, Indonesia (C)Tansa, KCIJ Newstapa, Tempo

The next morning, we went to the power plant site. When we stopped the car, a man approached on a motorcycle and started talking to our Indonesian driver.

“What are you doing?” the man said.

“We are just sightseeing,” the driver said.

The man left.

Thirty minutes after the encounter, we went to a mosque. Indonesia has one of the biggest Muslim populations in the world. Two men got off from a car and watched us while we were filming the religious service. The man we saw earlier was not there.

The WALHI representative speculated that the three men were security police or people employed by the utility. “Those people are always keeping close eyes on anti-power plant activities and any reporting related to that.”

When we started filming, two men drove closer to us, closely watching us (C)Tansa, KCIJ Newstapa, Tempo

Right before we arrived in Cirebon, we found representatives from U.S. and European non-profit organizations, who were there to investigate the power plant. Some who were at the house of an anti-power-plant resident fled through the back door when the police arrived. WALHI members and protesters told us to be careful. So we decided to wrap up the reporting for the day.

The next day, we made an appointment to see the leader of The People for Environmental Protection (RAPEL), an anti-power plant group. We decided to meet at our hotel as we wanted to avoid any monitoring. The hotel is situated 30 minutes from the power plant.

A piercing eyed and muscular man came to the hotel. Moh Aan Anwarudin, 33, is the leader of the group.

An interview with Moh Aan Anwarudin on Sep. 2 2017 (C)Tansa, KCIJ Newstapa, Tempo

Moh Aan Anwarudin’s involvement in the power plant issue goes back to 2007, when he was a college student. An information session was held by the utility company at the office of the village where he grew up in. Moh Aan Anwarudin went there to find out about the impact of the proposed power plant on their lives. There were only 20 to 30 people at the meeting.

The briefing did little to enlighten the residents. Yet a few days later, uniformed military and police officers came to the landowners of the planned plant site, Moh Aan Anwarudin remembered.

“They were forcing the residents to sell their land. Witnessing that made me angry for the first time. When you have the military and police (forcing it), It’s like blackmail,” he said.

Three months after the information session, in May 2017, Moh Aan Anwarudin launched a demonstration with 100 residents in front of the planned site. The protests continued every month and had grown to almost 3,000 people by August. Despite this, the construction continued.

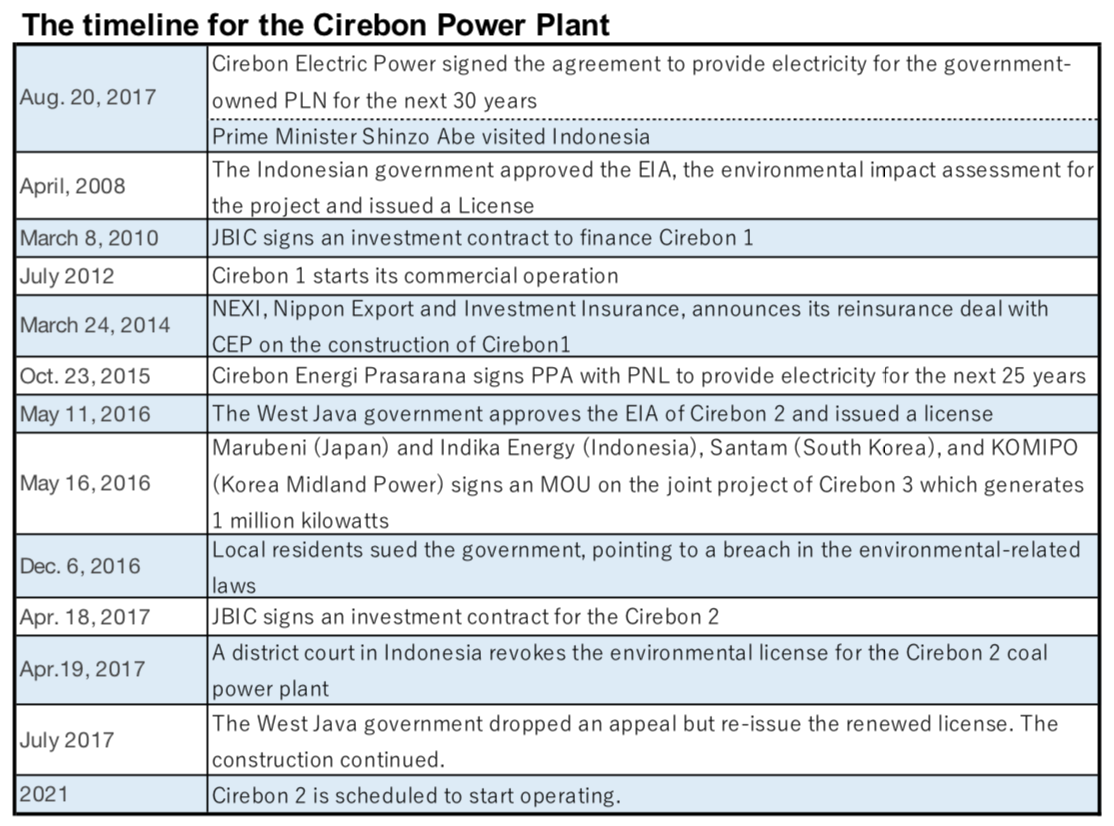

On Aug. 20, 2007 around the same time the protests were held, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe visited Indonesia with a group of 250 business people led by Fujio Mitarai, then-chairman of Keidanren, or Japan’s most powerful business lobby. It was one of the largest business missions ever accompanying a Japanese prime minister.

Abe arrived at the Grand Hyatt Jakarta (currently Ayana Midplaza Jakarta) at around 2 pm that day and attended the signing ceremony of the coal-fired thermal power plant at Cirebon together with the then Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono.

Ninety minutes after the ceremony, Abe went to the Intercontinental Hotel and made a speech, celebrating the 40th anniversary of ASEAN, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. During the speech, he touched on the environmental issues.

“Technology is advancing at a brisk pace. By taking advantage of this, we can protect the environment and bring economic growth at the same time,” said Abe.

Is what Abe said really true when two heads of the states attended the signing ceremony of a project that does not meet Japan’s own pollution control standards? What kind of project is it when the Indonesian military and police are involved in procuring of site and when reporting activities were put under strict surveillance?

Protest against the coal-fired thermal power plant in Cirebon and similar power plants. It was held as part of the Car Free Day event, on Sep. 14, 2014. Photo provided by RAPEL and NGO350.

“A 300-billion-Yen Project” led by Marubeni

Cirebon 1 has been operated by Cirebon Electric Power, which was created by Japanese, South Korean and Indonesian companies in 2012.

The office of the company that deals with anti-power plant activities , Aug. 31, 2017, Cirebon(C)Tansa, KCIJ Newstapa, Tempo

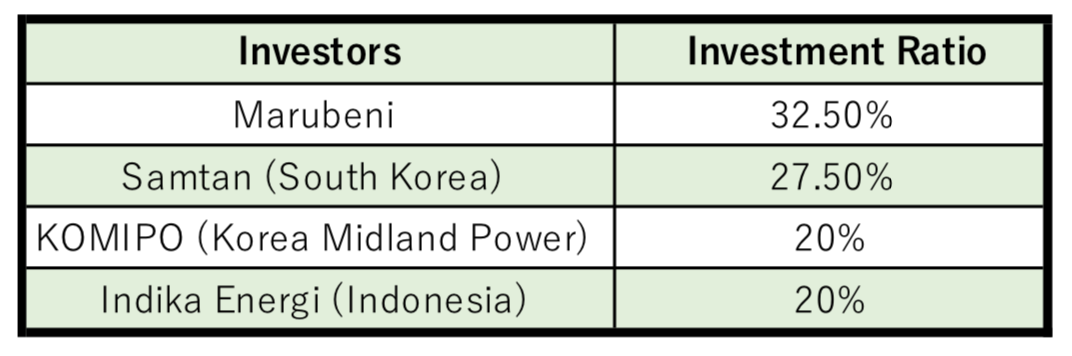

The biggest investor in Cirebon Power is Marubeni, which financed about a third of the project. Below is the list of investors and investment breakdowns.

Source: “Marubeni contributes to fixing the electricity shortage in Indonesia; Cirebon Coal-Fired Thermal Power Plant starts operating,” JBIC Jakarta, May 2013

Japanese and South Korean banks are investing a total of ¥67 billion (about $592 million) in Cirebon Electric Power. JBIC provides about ¥24 billion (about $212 million). The entity is backed by the Japanese government 100 percent and is under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Finance.

Marubeni is the biggest investor in the planned construction of Cirebon 2, at a cost of ¥226 billion (about $1.9 billion) (twice as expensive as Cirebon 1). Japanese utilities such as Tokyo Electric Co. and Chubu Electric Power also taking part in the project.

The Indonesian-government-owned PNL will buy the electricity generated in Cirebon 1 and Cirebon 2 for the next 30 years and 25 years respectively.

Greenpeace points out “the potential for deadly harm to locals”

Non-governmental organization Greenpeace published an alarming report on the Cirebon project. Lauri Myllyvirta, who specializes in air pollution at the organization, estimated the air pollution from the Cirebon 1 would kill hundreds of local residents, according to standards used by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the World Health Organization.

Below is the potential impact on local residents from pollutants from the plant.

1) An estimated 800 more people who would die earlier than average

2) The risk of stroke, lung cancer, and respiratory disease among residents will increase and children and the old will be more exposed to health risks

3)There will be 280 babies born every year with low body weight

Interview with Lauri Myllyvirta(C)Tansa, KCIJ Newstapa, Tempo

The Cirebon plants spew 20 to 30 times more air pollutants than state-of-the-art power plants in Japan

Myllyvirta’s analysis shows how the Cirebon 1 may harm the health of nearby residents.

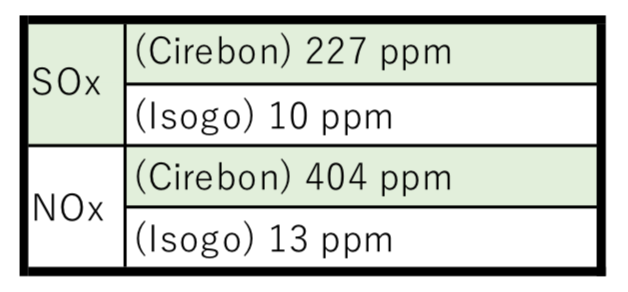

There are two main types of pollutants, SOx and NOx. The emissions from the Cirebon power plants contain a lot of these two pollutants. Compared to coal-fired thermal power plants in Isogo, Yokohama in Japan, one can see clear differences. The power plants in Isogo made technological improvements to cut pollution after signing a pollution prevention agreement with the city of Yokohama on March 31, 2004.

source: “Isogo thermal power plant completes its refitting” J-Power, 2009. AMDAL by the Indonesian government, April, 2008

Lack of Minimum Anti-Pollution System

What makes these two thermal plants so different in terms of these numbers of content of chemical substances?

The Cirebon power plant is not equipped with two systems that remove SOx and NOx emissions.

We made inquiries about the lack of the systems to Marubeni and JBIC.

“The Cirebon 1 project meets environmental standards in Indonesia and the agreement was struck with PLN based on the country’s energy policy and dialogue with the local residents. And this applies to any plant, including any environment-related facility, in Indonesia. So we alone cannot make decisions (about the anti-pollution systems.) The Indonesian side, including PLN, also recognizes Japan’s advanced technology,” Marubeni answered.

“In terms of the systems, the operator of the utility made an appropriate agreement with PLN, meeting the Indonesian standards at the time, and the country’s energy policy, and based on the dialogue with the local residents,” said JBIC.

It’s noteworthy that both Marubeni and JBIC blame the circumstances in Indonesia for the lack of the anti-pollution systems.

Yet, Kenichi Oshima, professor of environmental economics at Ryukoku University in Kyoto, said, “It’s unthinkable to have coal-fired thermal power plants in Japan without these anti-pollution facilities.”

Not installing the facilities saves the operators money.

Emre Gençer, a postdoctoral associate at the MIT Energy Initiative who specializes in efficient and integrated process design and renewable energy conversion and optimization, said equipping the power plant with the same anti-pollution technology as Isogo would increase operating costs by 17% to 25%. That is about ¥18 million (about $159,000) for the entire Cirebon 1 project.

Power Plants That Cannot Operate in Japan and South Korea

Japan and South Korea cannot build power plants similar to the Cirebon one because the two countries have more stringent pollution prevention regulations.

Chimney of the coal-fired thermal power plant near Kanci Kulon village, Aug. 31 2017 (C)Tansa, KCIJ Newstapa, Tempo

There are three levels of standards in regulating the concentration of NOx, depending on the total amount of emissions. The upper limit is 350 ppm, which the Cirebon plant fails to meet. Even though the amount of SOx emissions is also regulated, it’s not easy to make a comparison as the standards vary depending on the population and environmental situation.

In South Korea, each power plant is required to have the two systems, Flue-gas desulfurization (FGD) and Selective catalytic reduction (SCR) to remove SOx and NOx, respectively. 50 power plants in the country are all equipped with these systems.

This means that the Japanese and the South Korean companies built a coal-fired thermal power plant that cannot legally operate in either country. Riki Sonia, 29, a member of RAPEL, is outraged.

“Japan and South Korea have much better technology. But why aren’t they using that for us?” said Riki, who works with Moh Aan Anwarudin in the anti-power plant protest. “If they think it’s okay for the Indonesian people to suffer from pollution by using lower-quality technology, I cannot help but think that the Japanese and South Koreans are looking down on us.”

An interview with Riki Sonia, Sep. 2, 2017(C)Tansa, KCIJ Newstapa, Tempo

Yet the power plant in Cirebon continues operating and plans are underway to build Cirebon 2 and Cirebon 3. The Indonesian government shows no intention to adopt pollution prevention regulations as strict as the ones that would force the closure of such plants in Japan and South Korea. What are the political and business goals for this project for each player of the three countries?

(Originally published in Japanese on July 20, 2018. Numbers are calculated at the exchange rate of $1=113.12 yen.)

All the reporting was done by Tansa, KCIJ Newstapa, and Tempo with the help of FoE Japan, an international environmental non-governmental organization, and WALHI, an Indonesian environmental non-governmental organization.

[Footnote]

*1 Press release by Marubeni “MOU for the Indonesia Cirebon 3 coal-fired thermal IIP project” May 17, 2017 (https://www.marubeni.com/jp/news/2016/release/20160517.pdf)

*2 “Phasing out the coal-fired power plant in the U.S. and Europe: Investment in the coal-fired thermal power plant is unethical” Apr. 21, 2018 (https://www.asahi.com/articles/ASL4F3QVPL4FUTLZ00B.html)

*3 Study by the Universitas Padjadjaran (http://kknm.unpad.ac.id/kancikulon/profil-desa-2/)

*4 The Encyclopedia on Indonesia by Kenji Tsuchiya and Sumio Fukami, published by Doyu Publishing in 1994 (1991)

*5 Yomiuri Shimbun Morning edition on Aug. 21, 2007 “Daily activities of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe” “Indonesia signs EPA with Japan” JOGMEC, Aug. 20, 2007 (http://mric.jogmec.go.jp/news_flash/20070820/21674/)

*6 Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s speech in Indonesia 2007 “Japan and One ASEAN that Care and Share at the Heart of Dynamic Asia,” the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (https://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/press/enzetsu/19/eabe_0820.html)

*7 “Marubeni contributes to fix the electric shortage in Indonesia, Cirebon Coal-Fired Thermal Power Plant starts its operation” JBIC Jakarta, May 2013 (https://www.jbic.go.jp/wp-content/uploads/reference_ja/2013/05/2905/jbic_RRJ_2013023.pdf)

*8 “Indonesia guarantees project financing and political risk for the Cirebon coal-fired thermal power plant project” JBIC press release in 2010 (https://www.jbic.go.jp/ja/information/press/press-2009/0308-6025.htm)

*9 JBIC responded the inquiry via email on July 19, 2018

*10 “Chubu Electric Power joins the high-efficiency coal-fired thermal power plant in Indonesia” Press release by Chubu Electric Power in 2015 (https://www.chuden.co.jp/corporate/publicity/pub_release/press/3258254_21432.html)

*11 “JBIC to finance to expand the Cirebon coal-fired thermal power plant project in Indonesia” JBIC press release in 2017 (https://www.jbic.go.jp/ja/information/press/press-2017/1114-58532.html)

*12 Myllyvirta, Lauri, Assessing the air quality, toxic and health impacts of the Cirebon coal-fired power plant, 2018

*13 Marubeni’s response was sent via email on May 30, 2018 and JBIC send its response on the same day via email.

*14 Press release by Marubeni “MOU for the Indonesia Cirebon 3 coal-fired thermal IIP project” May 17, 2017(https://www.marubeni.com/jp/news/2016/release/20160517.pdf)

*15 As for the partnership with the non-Japanese news organizations and NGOs, please refer to Collaboration between Investigative journalism and NGOs published by Sairyu-sha Publishing in 2017

Coal Crusades: All articles

Newsletter signup

Newsletter signup