“Harmed by the Diet”: Politician Mizuho Fukushima on Japan’s sterilization victims

2021.12.01 14:30 Mariko Tsuji

Roughly 25,000 individuals were sterilized by the state under Japan’s postwar “Eugenic Protection Law” (1948–1996). As a way of taking responsibility for past wrongs, in April 2019 the Diet passed a new law that made all victims eligible for a one-time remediation payment.

However, two years later only 3.8% of the victims have received it.

Tansa interviewed Mizuho Fukushima, a Diet member who heads a group of lawmakers aiming to address Japan’s historical sterilizations, about how remediation can better reach survivors.

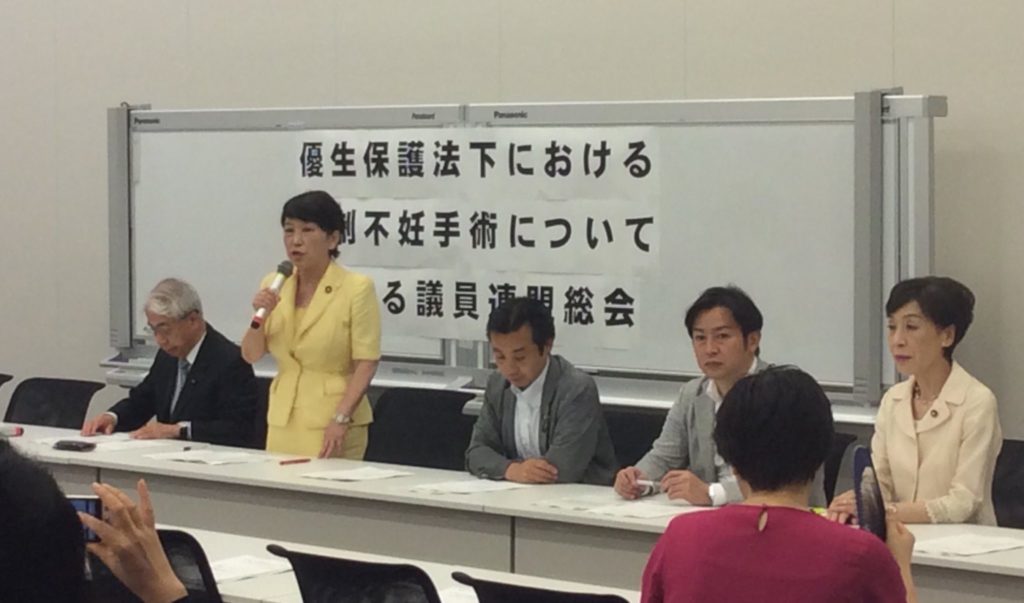

Mizuho Fukushima speaks at a meeting of the group of Diet members working to address the forced sterilization issue. Taken from a July 18, 2018 post on Fukushima’s Twitter.

Survivors unaware of new law

What can be done so more survivors receive the remediation payment?

I think the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) needs to spread the word a little more. I feel the effort isn’t coordinated enough, and if the MHLW had told us when they were tweeting about it, we could have retweeted them or cooperated in some other way. We want to take every opportunity to share information about this law. The MHLW working alone didn’t have much impact.

Only about 3.8% of victims have received the remediation payment. What do you think is the root cause of this?

Since these sterilizations took place a very long time ago, some individuals may not know what kind of surgery they had. Some may have already passed away, and some may be living in care facilities. The creation of the remediation law isn’t widely known, making it hard to reach victims. Compared to other diseases such as hepatitis [which was accidentally spread at government vaccination centers in the postwar period], there is very little publicity regarding sterilizations. There are no government-sponsored commercials on TV or radio.

How did your group of lawmakers decide not to contact individual victims?

The ruling party’s project team and our lawmakers’ group went back and forth on various points as we drafted the law, but in this case we both agreed it would be best not to contact individual victims [out of concern for their privacy].

In the name of privacy

What kind of cases did you imagine would constitute an invasion of privacy?

First of all, we have the question of whether it’s permissible to investigate victims without their consent. Since the government’s sterilization data is outdated, it’s necessary to go through residence records to find victims’ current address. It’s also possible that a stranger might open a letter sent to a victim’s former address.

And even if their address has not changed, the individual may have gotten married or started a family. For example, if a victim hasn’t told her husband that she was sterilized, it’s possible that sending such a letter might cause trouble in the family.

We felt it wasn’t right for the government to “out” victims. Outing someone without their consent wouldn’t be ok if they were an LGBTQ individual, and we were worried it would be similar with sterilization victims. One thing to consider is whether there is a way of contacting victims without outing them.

Japan’s sterilization program often targeted individuals with disabilities. Don’t you think informing someone they had been sterilized by the state is different from outing LGBTQ individuals?

It’s true that vulnerable individuals, such as people with disabilities, were targeted. In order to address this, we have been working with communities such as disability groups and leprosy NPOs to spread the word, even by word of mouth if necessary.

In the past, I have also worked with victims of hepatitis caused by government vaccinations, so I know how difficult it can be to inform someone they are a victim. There is also the issue of how to offer help to those who are in care facilities and who aren’t really aware of their surroundings. No matter how many posters we put up at medical institutions or care facilities or how many times we tweet, they will not be able to understand.

Some prefectures, such as Tottori and Yamagata, have been able to contact individuals while still protecting their privacy.

Thank you for this information, our lawmakers’ group wasn’t aware of the details. However, there is still a debate on whether it’s a good idea to inform relatives who do not know about the surgery.

Video interview with Saburo Kita, who was sterilized in Miyagi Prefecture at age 14, without explanation and without his consent.

Harmed by the Diet

Not many victims have received remediation, even two years after the law was created. Do you think your group of lawmakers working on this issue should review the rules?

Maybe. We created the remediation law because the state is responsible for what happened. The Eugenic Protection Law was the first law passed in postwar Japan that was introduced by Diet members [as opposed to the cabinet], mainly from the House of Councillors. Since legislation by the Diet caused the harm, I believe that legislation must address it. You’re right to say that we should closely follow up on this issue.

What would happen if your group of lawmakers asked the MHLW to change its mind on not directly contacting individuals?

Many of the victims will pass away in another 10 or 20 years. It would be meaningless to say we provided remediation at that point. Rather than immediately doing an about-face on contacting individuals, we should consult with NGOs and prefectural governments to see what can be done. It is also very possible to extend the period of eligibility for remediation stipulated by the law.

(Originally published in Japanese on Oct. 30, 2021. Translation by Annelise Giseburt.)

Forced Sterilization: All articles

Newsletter

signup

Newsletter

signup