Warning received re operators of app for trading sexually explicit images(36)

2025.11.18 16:12 Mariko Tsuji, Makoto Watanabe

The app Album Collection, which was used for trading nonconsensual and illegal sexually explicit images, generated millions of dollars in profits. Tansa received a warning that its operators were connected with the underworlds of both Japan and the US.

(Illustration by qnel)

Exploitation and harm from digital sexual abuse is eternal.

This is what I have come to believe through investigating digital sexual abuse since 2022.

Sexual images and videos of women and children are bought and sold online. Even though it may start with just one post, an image can spread to thousands — even millions — of people in the blink of an eye. Under Japan’s current system, it is impossible to completely erase images once they have been shared. And the victims are forced to suffer continuously.

Sexually explicit images are sometimes used for blackmail, fraud, and violence, or to dominate and belittle the victim.

Hidden cameras and hacking are among the methods used to access such images — which means that anyone could become a victim of online sexual abuse.

At the same time, a variety of people, from minors to adults, have become perpetrators.

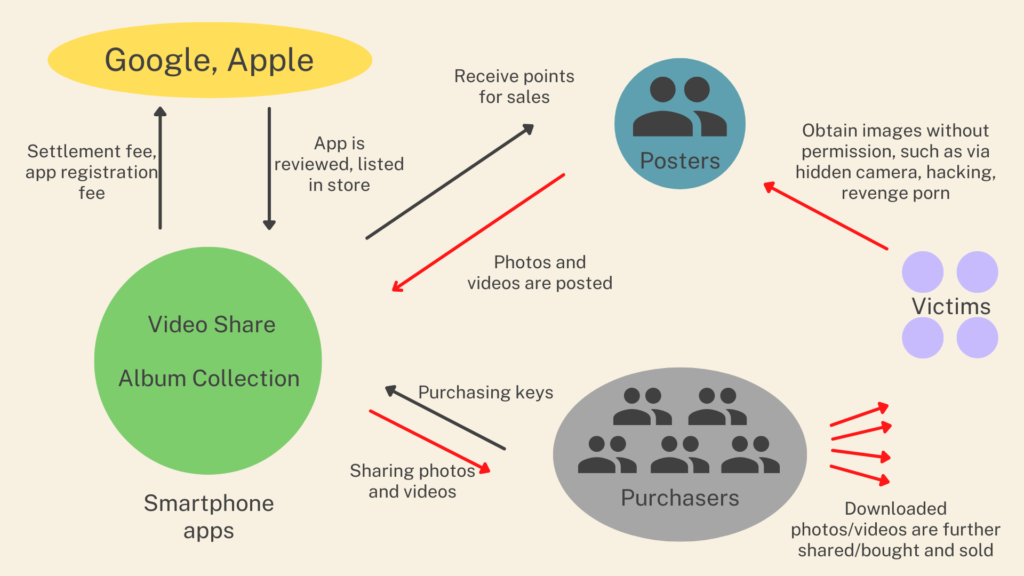

Money used to purchase sexually explicit images has lined the pockets of app and website operators, payment processors, and the operators of major platforms like Google and Apple. Digital sexual violence is integrated into a massive business ecosystem.

Government agencies and investigative bodies merely stand by and watch. In today’s society, victims of online sexual violence find little support or recourse.

My reporting to date has been in an effort to dismantle this exploitative system and prevent further harm.

Take, for example, the app Album Collection, which was used to trade sexually explicit images, including child sexual abuse material. Album Collection was available for anyone to download on Apple’s App Store. There was even a period when the app ranked number one in the App Store’s “Photos & Videos” category.

Album Collection ceased operations in January 2024, as a result of Tansa’s joint investigation with the NHK Special “Innovative Investigations.”

However, there was still much we didn’t know.

Had all the nonconsensual images uploaded to the app been deleted, without being leaked?

Who had pocketed the millions of US dollars generated from the trade in sexually explicit images?

Who were the app’s real operators?

Among these questions, the last was particularly crucial. Without knowing the app’s real operators, it would be impossible to hold them criminally liable or demand compensation for the victims.

However, Japan’s police and public prosecutors had not launched an investigation into Album Collection. The app’s victims are left to suffer in silence, while similar crimes are repeated again and again.

Tansa and the NHK reporting team continued our investigation even after Album Collection ended its operations. In doing so, we found the potential involvement of organized crime, as well as harm that extends across various apps and digital tools. In the coming articles, I will share what we found.

A friend among the victims

First, allow me to summarize our investigation up to this point.

In the summer of 2022, I began investigating online sexual abuse after learning that a friend’s images and videos were being sold online.

That’s when I found the apps Album Collection and Video Share. Huge volumes of sexually explicit images, including videos showing children being sexually assaulted, were being traded on both apps. Both were available in Apple and Google’s apps stores, where anyone could download them.

The apps acted as hubs for users to both upload and download images. Users and app operators profited when other users paid to download images. Because the apps used Apple’s payment system, Apple also earned processing fees from the transactions.

I examined the apps closely, in cooperation with white hat hackers. We found that Album Collection was connected with two similar apps that had been created before it. The operators were men named Kenichi Takahama and Keisuke Nitta.

The two were the founder and former CEO of an affiliate services company called First Penguin (formerly infotop). We tracked them down to interview them, and the pair acknowledged that they had operated the app despite knowing that illegal images were being traded. They said they sold Album Collection in 2020, with the app still woefully unequipped to prevent online sexual abuse.

Album Collection’s structure

Revenue of over a million dollars

Keisuke Nitta had sold Album Collection to a company incorporated in Hawaii called Eclipse.

A man named William Leal was listed in Hawaii’s public records as Eclipse’s representative. However, it was difficult to find information on him, and we were left in the dark.

In the meantime, the situation kept getting worse. In December 2023, Album Collection reached the top ranking in the App Store’s “Photos & Videos” category.

I considered this an emergency, as Album Collection was used to trade child sexual abuse material and other nonconsensual images. On Dec. 15, 2023, Tansa sent an email addressed to Apple CEO Tim Cook, questioning whether Apple would remove Album Collection from its platform. Three days later, on Dec. 18, the app had disappeared from the App Store.

Two weeks after being removed by Apple, on Dec. 31, 2023, Album Collection announced that it was “ending its services.”

However, at that point, all we knew about Album Collection was that it was operated by a Hawaiian company called Eclipse, whose representative was named William Leal. Together with the NHK Special reporting team, who we began working with in fall 2023, Tansa headed to Hawaii.

As a result of that visit, we were able to interview the accounting firm handling Eclipse’s finances. We learned that operating Album Collection generated an annual revenue equivalent to hundreds of millions of yen (over a million US dollars), paid via platforms such as Apple.

We also learned that multiple people, not only Leal, had been involved in establishing Eclipse.

The key appeared to be a person named Shaun Hart, who was of both Japanese and American decent. His Japanese name was Satoshi Kominami.

Leal, then CEO of Eclipse, had been involved in establishing the company and opening a bank account for it at Hart’s request, according to Leal’s father. The accountant who had been present at the meeting when Eclipse was founded also recognized Hart’s face and name. Had Hart been at the center of Album Collection’s operations?

We also learned from local news reports that Hart was wanted in the United States. Charged with theft, misuse of personal information, and drug possession, he had fled to Japan before his trial.

Operating out of a US military base in Okinawa, Hart was arrested in Japan in 2021 on suspicion of importing cocaine and marijuana from the US.

That was where our investigation stood.

Only cosmetic changes to the app

However, for three reasons, I didn’t think we could leave it there.

First, I had a suspicion that Album Collection’s operators were continuing their business while merely changing the app’s name and appearance.

Keisuke Nitta, who claimed he had operated Album Collection until 2020, had operated similar apps under different names between 2014 and 2020: Photo Capsule, Video Container, and then Album Collection. The trading of sexually explicit images, including illegal images, had occurred on all three apps.

Nitta said the reason he changed the apps was because illegal content had increased. However, in reality, he had guided users from the old app to the new one. He broke camp before the app’s legality could come into question. Those connected with Eclipse, which bought Album Collection from Nitta, may still be profiting from the trade of sexually explicit images via a different app under a new name.

Second, I wondered whether all the nonconsensual and illegal photos and videos uploaded to Album Collection had been properly deleted. If the operators still had access to this data, they could spread the images again. They also were responsible for the harm already caused and should compensate the victims.

Although I sent these questions to Album Collection via its contact form, I never received a reply.

Third, we had never fully grasped who exactly was operating the app. When the operators did respond to my questions via the contact form, they only even identified themselves as “Album Collection Executive Committee.” Without resolving these issues, apps and websites for trading nonconsensual sexually explicit images will continue to be created. Even now, many such platforms exist, spreading further harm.

That’s why I continued my investigation.

“How much power he wields in the underworlds of Japan and the US”

Following our reporting in Hawaii, we continued searching for Shaun Hart. I suspected that William Leal, the registered president of Eclipse, was merely a figurehead, and that Hart was the one really in control of the operation. Leal’s father had told us that William was used by Hart.

I also found it strange that Hart had been able to flee to Japan despite being wanted by US law enforcement. Did he have some way of gaining the cooperation of others?

As I was mulling over these questions, I received an email from someone who had seen Tansa’s reporting. They said they knew Hart.

“You have no idea how much power Shaun wields in the underworlds of both Japan and the US,” they wrote.

To be continued.

(Originally published on May 30, 2025.)

Uploaded and Re-Uploaded: All articles

Newsletter

signup

Newsletter

signup