Six legal revisions enacted in one month: How public anger changed South Korean society (part 2)(9)

2023.03.30 12:45 Mariko Tsuji

Stricter penalties were implemented regarding sexually explicit images taken without the subject’s consent, victims were given more protection, and new regulations were made for platform operators.

(Illustration by qnel)

After the Nth Room case became public, citizens’ anger erupted in South Korea through national petitions and protests. How could the recurrence of such crimes be prevented? President Moon Jae-in promised citizens a thorough investigation and a revision of the law.

In Japan, the police — saying the scope of existing laws limits their reach — have not taken serious steps to crack down on digital sex crimes, and the “criminals” who spread sexually explicit photos and videos remain unchecked.

In South Korea, what kind of laws were created by the president’s call to action, driven by the voice of the people?

Making even possession illegal

The Nth Room case involved a group of perpetrators, mostly in their teens and 20s, who sexually assaulted their victims and sold their photos and videos via the Telegram messaging app. There were many minors among the victims. Cho Ju-bin, one of the main perpetrators, was arrested by the police in March 2020.

In May of the same year, two months after the police’s crackdown, the first revision was made to South Korean law to prevent similar incidents. From there, a total of six laws were amended over the course of the month.

The Sexual Violence Punishment Law was revised in response to how the crimes were carried out in the Nth Room case. In the case, photos and videos were taken without the victims’ consent and used to threaten and coerce them. The videos were viewed by chat room members who paid a high fee to enter the rooms.

Under the revised law, photographing a person without their consent for sexual purposes is punishable by imprisonment for up to seven years or a fine of up to 50 million won (about $38,300).

The revision also stipulated that it is a crime to use said images to intimidate a person or to use threats to violate their rights or make them comply with demands. These acts were not previously recognized as crimes. Threats are punishable by a minimum of one year in prison and coercion by threats is punishable by a minimum of three years.

The revision also specifies that possessing or viewing an image of a victim is also a crime, and it comes with another newly established punishment. Because of the lack of corresponding laws, the majority of the chat room operators and the estimated 260,000 members in the Nth Room case were not charged with crimes. Citizens called for the perpetrators of these crimes to be strictly punished as well.

Comparing these laws with those in Japan reveals a stark difference. In Japan, taking photos without the subject’s consent is only regulated by local ordinances. Viewing or possessing sexually explicit images taken without the subject’s consent is also not a crime, as long as the images are not child sexual abuse images.

The Revenge Porn Prevention Act regulates the dissemination of sexually explicit images taken without the subject’s consent or giving them to someone for the purpose of dissemination. However, it is insufficient without also regulating the possession and viewing of said images.

The apps I have been reporting on, “Video Share” and “Album Collection,” have a system where photos and videos purchased by users are automatically downloaded to a folder in the app. Perpetrators repost the downloaded images and make money by selling them to other users for further viewing. Possession and viewing of these images make the damage spread.

From punishment to protection

An amendment to the Youth Protection Law aimed to eliminate the very ground that produces victims. Girls who had been victims of sex trafficking were no longer subject to “punishment” or “rehabilitation guidance” but to protection.

The Stand Up Against Sex-Trafficking of Minors, which supports young victims of sexual exploitation, had been working to pass this legal reform since before the Nth Room case. At the center, former female victims of sexual exploitation work to support victims, in addition to lawyers, doctors, clinical psychologists, and other professionals from a variety of fields.

I interviewed Kwon Juri, the center’s director. Kwon explained that the amendment to the law was significant because it made it easier for girls to consult with someone about their situation. Before the amendment, the female victims of sex trafficking were also subject to punishment under the law, so they were afraid to confide in others.

Some girls were subjected to threats and sexual violence and forced into prostitution. In one case, a girl was gradually asked to send sexual photos and videos of herself to an online acquaintance whom she had gotten close with, and was then threatened using the images she had sent.

But, often, the girls are blamed by their parents and the police for “bringing this upon themselves,” and they are left to deal with the damage on their own.

“Digital sex crimes do not occur in isolation but are connected to various forms of sexual exploitation, such as sex trafficking,” said Kwon. “As long as there is a tendency in society to blame the victim, such exploitation will not disappear. The fact that this amendment to the law has changed ordinary citizens’ perception is a step forward.”

The final amendments

Of the six amendments to the law following the Nth Room case, the last two target telecommunications carriers and platforms.

The first is a law that regulates information and communication service providers and prevents the distribution of illegally obtained images through their services.

The law requires operators that meet certain criteria to submit annual reports. In addition, if any illegally obtained images are exchanged, necessary measures must be taken, such as deleting the material or blocking the communication connection.

The second revision strengthened regulations on businesses that provide online services. Businesses must report the distribution of illegally obtained photos and videos on their websites, etc., and take technical and administrative measures to prevent their distribution.

I found these legal revisions groundbreaking. Even if individual perpetrators are arrested, new perpetrators will appear on the same platform one after another. It is necessary to regulate the apps and websites that are hotbeds for crime in order to prevent further damage.

Japan does not have any similar laws regulating platforms and telecommunications carriers. Why is there no progress?

According to Hankyoreh reporter Oh Yeon-seo, there was significant pushback from affected corporations when South Korea revised these laws regulating telecom operators and platforms. Is there a similar or even more serious reason for the lack of legal protections in Japan? I will continue to report on this issue.

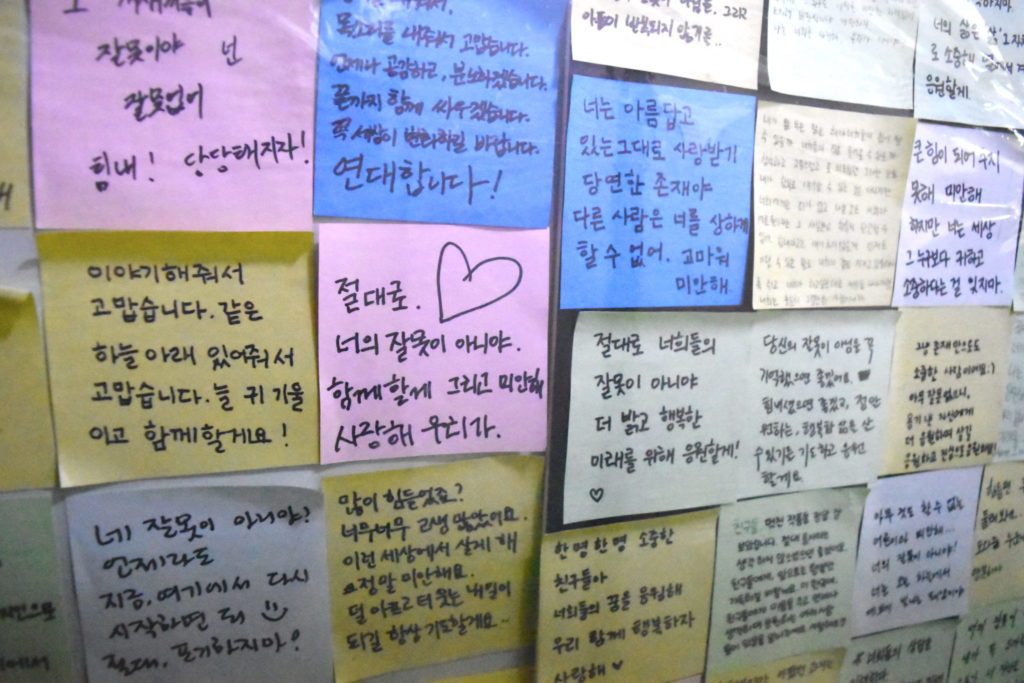

Messages received by the Stand Up Against Sex-Trafficking of Minors. The note in the center reads “It’s never your fault.” Photo taken on Feb. 8, 2023, by Mariko Tsuji.

To be continued.

(Originally published in Japanese on March 15, 2023.)

Uploaded and Re-Uploaded: All articles

Newsletter signup

Newsletter signup