4 min read

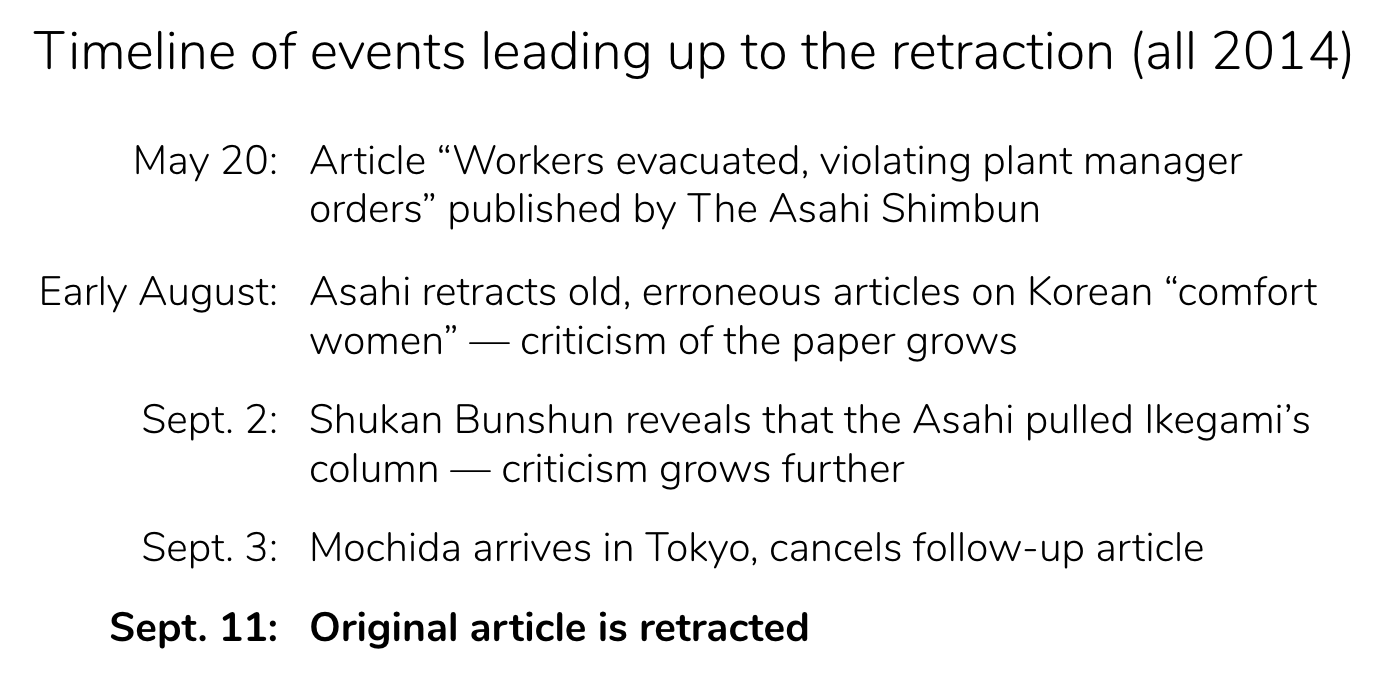

The Asahi Shimbun’s follow-up to its article on Fukushima No. 1 plant manager Masao Yoshida’s testimony about the 2011 nuclear disaster was set for publication on Sept. 5, 2014. The piece, intended to respond to criticism the original article had received, raised the question of who will deal with a severe nuclear accident like Fukushima.

But, with paper’s management in disarray, the follow-up was scrapped on Sept. 3.

The director called up from Osaka

That day, managing director and representative of the Asahi’s Osaka head office Shuzo Mochida arrived in Tokyo. With experience in the political news section, Mochida was said to be an adept strategist. President Tadakazu Kimura had summoned him as a crisis manager to help quell the mounting criticism aimed at the Asahi.

Mochida called four editorial managers into his office on the 15th floor of the paper’s Tokyo headquarters: General Manager Hayami Ichikawa, General Editor Tsutomu Watanabe, Assistant General Manager Isao Kikuchi, and Sei’ichi Ichikawa, head of the special investigative section responsible for the Yoshida article.

The crisis manager wanted an explanation of its follow-up.

Spiking the follow-up

Mochida was furious when he heard the details of the piece. He felt it didn’t reflect the Asahi’s increasingly precarious situation.

The day before Mochida arrived in Tokyo, weekly magazine Shukan Bunshun revealed that the Asahi had pulled a column by contributor Akira Ikegami. The revelation caused an uproar within the paper, with desk editors mobbing their superiors’ office to demand an explanation. One editorial manager described it as “the collapse of corporate governance.”

Ikegami’s column, intended for publication on Aug. 29, had been pulled because it reproached the Asahi for not issuing an apology when the paper retracted its past erroneous articles about comfort women. When he read the draft, President Kimura had said, “I’ll have to step down if we run this.”

Mochida told the four editorial managers to revise the follow-up Fukushima article so that it examined why the original was criticized rather than pushed back against the abuse. In other words, he instructed them to work under the assumption that the Yoshida article had contained some error that invited reproof.

After dismissing the editorial managers, Mochida summoned the political news section’s deputy editor, the deputy head of the special investigative section, and a senior staff writer. He charged the trio with creating his new vision for the follow-up.

To quell the criticism

Around that time, members of the city news and science and medical news sections were increasingly vocal in their opinion that the wording “violated manager orders” had caused the criticism of the Yoshida article.

“That phrase is at the center of the problem. If we don’t address that point, the bashing won’t die down, no matter how detailed the follow-up may be” was the prevailing opinion at a desk editors’ meeting on Sept. 3.

It was true that, in the confusion at the nuclear plant, Fukushima No. 1 workers had acted contrary to their manager’s order. But discussion at the meeting was preoccupied with how to quell the criticism aimed at the paper.

From then on, the Asahi shifted its priorities from “As a news organization, what do we want to convey?” to “What can we do to assuage these attacks?”

Restoring plant workers’ honor

The principal members of the Yoshida testimony team were special investigative section reporter Hideaki Kimura and digital senior staff writer Tomomi Miyazaki.

On Aug. 28, they received a draft of the fiscal year 2015 company brochure, which featured Kimura and Miyazaki as the reporters behind the Yoshida testimony scoop.

The draft brochure included the following statement from Kimura, under the title “Reporting the nuclear accident: Remembering readers’ rebuke and defending their right to the truth.” Here’s what it said.

“On March 11, 2011, I was at the Tokyo Electric Power Company headquarters in Uchisaiwaicho, Tokyo. I was the first reporter to arrive, having rushed there right after the earthquake. But as the nuclear accident continued to worsen, I wasn’t sure how best to gather information. I’m still frustrated by the shortcomings of my reporting that day.

“Readers also harshly criticized the reporting done by we members of the mainstream media; they compared our coverage to how the media simply parroted the government’s lies during World War II. Since the disaster, I have endeavored never to forget their rebuke.

“Yoshida’s testimony greatly contributes to our understanding of this unparalleled nuclear accident. That may be the reason why I was entrusted with the transcripts. And that’s why I had to make them public.

“With readers’ censure following 3.11 always in mind, I will continue to work hard to defend their right to the truth.”

On Sept. 3, one week after being sent the draft brochure, investigative section head Ichikawa contacted Kimura to tell him that he was off the Yoshida testimony team.

Just after 2 p.m. the next day, the two met in the investigative section office. “We have to restore the honor of the 650 workers [who evacuated],” Ichikawa said. “The paper could be sued for defamation.”

Ichikawa also called Miyazaki to tell him that he was off the team.

After the revelation on Sept. 2 that Ikegami’s column had been pulled, it felt like everything had unraveled in an instant.

At a Denny’s

At around 9:30 p.m. on Sept. 4, the two reporters met at a Denny’s in Suidobashi, near Tokyo Dome.

“We should be prepared for the worst,” said Miyazaki, sitting across from Kimura.

The worst came a week later.

… To be continued.

(Originally published in Japanese on Nov. 12, 2019)

Burying Japan’s Nuclear Secrets: All articles

Newsletter signup

Newsletter signup